Verben die durcheinanderbringen! (VDD)

Werbung

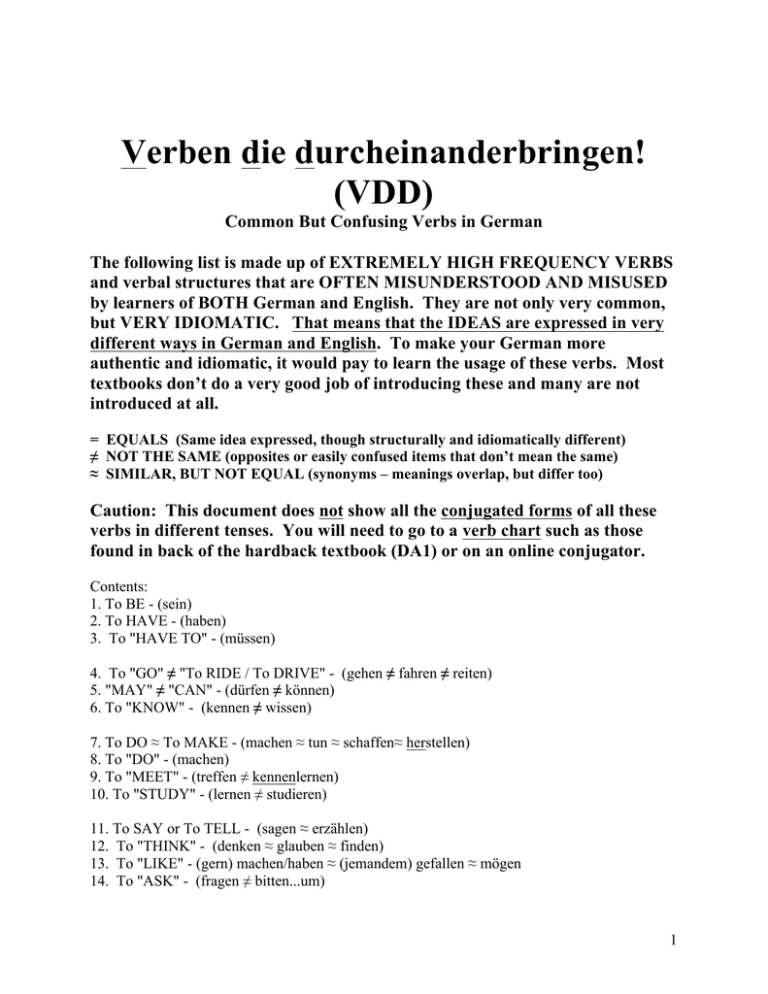

Verben die durcheinanderbringen! (VDD) Common But Confusing Verbs in German The following list is made up of EXTREMELY HIGH FREQUENCY VERBS and verbal structures that are OFTEN MISUNDERSTOOD AND MISUSED by learners of BOTH German and English. They are not only very common, but VERY IDIOMATIC. That means that the IDEAS are expressed in very different ways in German and English. To make your German more authentic and idiomatic, it would pay to learn the usage of these verbs. Most textbooks don’t do a very good job of introducing these and many are not introduced at all. = EQUALS (Same idea expressed, though structurally and idiomatically different) ≠ NOT THE SAME (opposites or easily confused items that don’t mean the same) ≈ SIMILAR, BUT NOT EQUAL (synonyms – meanings overlap, but differ too) Caution: This document does not show all the conjugated forms of all these verbs in different tenses. You will need to go to a verb chart such as those found in back of the hardback textbook (DA1) or on an online conjugator. Contents: 1. To BE - (sein) 2. To HAVE - (haben) 3. To "HAVE TO" - (müssen) 4. To "GO" ≠ "To RIDE / To DRIVE" - (gehen ≠ fahren ≠ reiten) 5. "MAY" ≠ "CAN" - (dürfen ≠ können) 6. To "KNOW" - (kennen ≠ wissen) 7. To DO ≈ To MAKE - (machen ≈ tun ≈ schaffen≈ herstellen) 8. To "DO" - (machen) 9. To "MEET" - (treffen ≠ kennenlernen) 10. To "STUDY" - (lernen ≠ studieren) 11. To SAY or To TELL - (sagen ≈ erzählen) 12. To "THINK" - (denken ≈ glauben ≈ finden) 13. To "LIKE" - (gern) machen/haben ≈ (jemandem) gefallen ≈ mögen 14. To "ASK" - (fragen ≠ bitten...um) 1 15. To "LIVE" - (leben ≈ wohnen) (16-20) SEPARABLE PREFIX VERBS 16. kommen (an, aus, ein, be-) 17. ziehen (aus, ein, um) 18. stellen (vor, aus, auf, ein) 19. steigen (ein, aus, um) 20. nehmen (mit, zu, ab, auf, heraus, be-) (21-25) NON-SEPARABLE PREFIX VERBS 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. sprechen ≠ besprechen ≠ versprechen schreiben ≠ beschreiben ≠ verschreiben ≠ ausschreiben stehen ≠ bestehen ≠ verstehen fehlen, befehlen, empfehlen suchen ≠ besuchen ≠ versuchen 26. To "TRY" - (probieren ≠ versuchen) 27. To "BECOME" ≠ To "GET" / RECEIVE - (werden ≠ bekommen) 28. To EAT - essen ≠ fressen 29. To LAY ≠ To LIE - (legen ≠ liegen) 30. To "TEACH" - (unterrichten ≠ beibringen ≈ lehren) 31. To KILL ≠ To DIE - (töten ≈ umbringen ≠ sterben ≈ um das Leben bringen) 32. To "BE ABOUT" - (sich handeln ≈ umgehen) 33. To "FIGHT" - (diskutieren ≈ streiten ≈ kämpfen) 34. To "TAKE PLACE" - platznehmen ≠ stattfinden 35. –IEREN verbs 36. „Oklahoma“ Verbs 37. MODAL Verbs 1. To BE - (sein) These one is a BIGGIE. It means “to be.” It is an irregular verb in its conjugation (the forms it takes with different subject pronouns) and is used in a minority of cases in the “perfect” tense, which doubles as the “conversational past” tense. This is a verb which you must know in and out and be “automatic” in your ability to use it. 2. To HAVE (haben) These one is also a BIGGIE. It means “to have.” It is an irregular verb in its conjugation (the forms it takes with different subject pronouns) and is used in a minority of cases in the “perfect” tense, which doubles as the “conversational past” tense. This is a verb which you must know in and out and be “automatic” in your ability to use it. When we get into "conversational past" (which is more precisely the "present perfect" tense), you use "haben" a lot. "I played 2 soccer." = "Ich habe Fußball gespielt." = (I have soccer played.) or "He said, he saw the movie." = "Er hat gesagt, er hat den Film gesehen." (He has said, he has the film seen.) 3. To "HAVE TO" - (müssen) Although the German modal verb (See # 35) "müssen" can mean "must," (it even looks the same, since it's a cognate), I emphasize and prefer the less formal (and therefore, MUCH MORE COMMON and idiomatic) "to have to." Which would you say? "I have to do my homework" or "I must do my homework"? = "Ich muss meine Hausaufgaben machen." 4. To "GO" ≠ "To RIDE / To DRIVE" - (gehen ≠ fahren ≠ reiten) Although the two verbs "gehen" and "fahren" can be translated "to go," they are used somewhat differently. "Gehen" can generally be used to talk about "going" from one place to another, by foot, by bike, by car, etc. It can also mean "to walk," although you may want to clarify by saying "Ich gehe zu Fuß." = "I go on foot." "Fahren," on the other hand REQUIRES SOME SORT OF VEHICLE. It can, however, refer to either the "driver" or the "rider" or "passanger." For example, "Ich fahre mein Rad," "Ich fahre mein Auto," and "Ich fahre mit dem Zug" all use the same verb, but would be translated into English as "I ride my bike," "I drive my car," and "I go by train." (three different verbs) Both "fahren" and "reiten" can both mean "to ride“ but the latter ONLY means to "ride on an animal“ (most commonly a HORSE). “Fahren” often means “to drive” when the operator is the “person behind the wheel” but means “to ride in” (a vehicle of some sort) as well. “I drive a car” = “Ich fahre ein Auto.” “I ride in a bus.”=“Ich fahre mit dem Bus.” 5. "MAY" ≠ "CAN" - (dürfen ≠ können) Both of these are often translated and used as "can," but "dürfen" means more accurately "allowed to" or "may." "Können" means "to be able to." 6. To "KNOW" (kennen ≠ wissen) These two verbs both can mean “to know.” “Kennen” is “to be acquainted with” another person or persons or even a place. “Wissen” is “to know information.” Examples: “Ich kenne sie.” = „I know her (personally.“ „Ich weiß, wo sie wohnt.“ = “I know where she lives.” 7. To DO ≈ To MAKE (machen ≈ tun ≈ schaffen≈ herstellen) These four verbs are all similar but have idiomatic differences between themselves in German as well as compared to English. “Machen” is the most common of the verbs. It can mean both “to do” and “to make” in German. (*Remember that German does not have a progressive tense, -“is doing”- so “Ich mache…” can mean all of the following: “I do…” “I am doing…” “I make…” and “I am making…” In English, “to do” usually connotes an activity or action; “to make” usually connotes a physical product. “I’m making a cake.” Another source of confusion is that in English, we use the verb “to do” to add emphasis to a statement; for example, “He DOES do that often!” or “They DO indeed have good grades!” Also in English, we use “to do” to phrase question. “Does he play soccer?” or “Do they go to the beach?” Using a form of “to do” for emphasis or questions is NEVER done in idiomatic German. The previous two questions would be rendered “Spielt er Fußball?” (Plays he soccer?) or “Gehen sie zum Strand?” (Go they to-the beach?). German “does indeed” also add emphasis to declarative sentences, but 3 uses other words such as doch, zwar, sicher, ja (though, indeed, certainly, yes) to accomplish that same purpose. “Tun” is often used interchangeably with “machen.” For example, “What can one do?” or “What can you do?” can be either “Was kann man machen?” or “Was kann man tun?” German, however, does not use “tun” to convey “to make something concrete,” but rather as a synonym for “to put.” For example, “He puts his books in the backpack.” “Er tut seine Bücher in den Rucksack.” The verb “schaffen” is more specific. It really means “to manage” “to arrange” “to take care doing something” or “to get something done.” So, when we say “We can do it!” or “We’ll get ‘r done!” Germans would say „Wir schaffen es!“ When you want to encourage someone that he or she can "do" something (as in "accomplish), you say.."Du kannst es schaffen!" The verb „herstellen“ is even more specific. It means „to manufacture.“ For example, „BMW manufactures cars in Germany.” “BMW stellt Autos in Deutschland her.” (Notice that „herstellen“ is a verb with a „separable prefix.“ (See # 16-20 ) 8. To "DO" (machen) Not only is „machen“ a verb with some idiomatic differences (See # 7 above), but it also can be formed into many “separable prefix” verbs, all having different meanings. (Note, as in # 16-20, “separable prefix” verbs are ones that are expressed with a PREFIX - usually a preposition - that SEPARATES and MOVES to the end of a clause when conjugated, but is a true prefix when given in the infinitive form (in dictionaries, for example). Here are some of the verbs formed from "machen" which use a separable prefix: mitmachen = to participate zumachen = to close; to shut aufmachen = to open fertigmachen = to finish; to make ready 9. To "MEET" (treffen ≠ kennenlernen) This is a commonly confused pair of verbs. Both can mean “to meet” in English, but have very different meanings. “Treffen” is “to meet up with” (someone you already know) or “to get together.” For example, “They get together at Café Julia.” (They meet there.) Sie treffen (sich)bei Café Julia.” (“sich” = “each other”) “Kennenlernen” is a separable prefix verb literally meaning “to learn to know” (to-be acquainted-to-learn). (See # 16-20) It is used only when people are meeting for the first time. “They meet at Café Julia.” (i.e. They didn’t know each other beforehand.) „Sie lernen sich bei Café Julia kennen.“ "Treffen" is an "Oklahoma verb" (See #36). 10. To "STUDY" (lernen ≠ studieren) Both of these verbs have to do with “studying“ or “learning.“ “Lernen” is what elementary and secondary students do, they”study” and “learn.” “Studieren” is only used with UNIVERSITY students. (By the way, the noun “Student” is also only used for people at University or College.) “Er studiert Biologie” could be “He’s studying biology” or “He’s majoring in biology.” 4 11. To SAY or To TELL (sagen ≈ erzählen) Both of these verbs can mean “to tell.” “Sagen,” which can also mean “to say,” is basically to “communicate something with words.” “Erzählen” is “to tell a story.” There is usually a narrative involved. Examples: “Er sagt uns den Titel der Geschichte.” = “He tells us the title of the story.“ „Er erzählt uns die lange Geschichte.“ = “He tells us the long story.” 12. To "THINK" (denken ≈ glauben ≈ finden) All three of these verbs can mean „to think“ in the sense that you’re giving your OPINION. But they aren’t always interchangeable!! “Denken” means “to think thoughts.” You can say “Ich denke, er ist nett.” = “I think he is nice.“ You can also say, "Ich glaube, er ist nett," or "Ich finde, er ist nett." (I believe, he is nice.) (I find, he is nice.) But “I’m thinking about him." is "Ich denke über ihn." If you are talking about your "beliefs," you have to use "glauben." If you are talking about "thinking thoughts," you have to use "denken." "Finden" is of course used when you "find" someone or something you have been looking for. 13. To "LIKE" (gern) machen/haben ≈ (jemandem) gefallen ≈ mögen All of these verbs more or less mean “to like.” It’s more their sentence structure that differs. “Gern” is an adverb, not a verb. “Gefallen” is a verb meaning “to please” that is used with the dative (indirect object) pronouns. “Mögen” is a modal verb. So … “I like ___” can be rendered…Ich mache Fußball gern….Berlin gefällt mir...Ich mag Pizza. (The first is an action, the second is “pleasing to the eye” and the third is a particular concrete thing.) 14. To "ASK" (fragen ≠ bitten) Both of these verbs can mean “to ask.” “Fragen” is “to ask for information.” “Bitten…um” is “to ask to have or do something” or “to request.” For example, "I ask her, if she has a pencil." (I'm seeking information.) "Ich frage sie, ob sie einen Bleistift hat." (I ask her, whether she a pencil has.) But..."I ask her for a pencil." is "Ich bitte sie um einen Bleistift." = (I request her about a pencil.) 15. To "LIVE" (leben ≈ wohnen) Though both of these verbs can be translated “to live,” the verb “leben” means basically “to have life.” Its opposite is “sterben.” “Wohnen” on the other hand means “to reside.” It only refers to where your dwelling is. You can say, for example, either "Ich wohne in Elkins." or "Ich lebe in Elkins." But... it's better to say "Er wohnt in einem Haus." = "He lives in a house." "Er lebt noch" = "He's still living." (not dead) "Er lebt noch in Elkins" = "He still lives in Elkins." (He didn't move.) Be careful! "Leben" and "lieben" (to love) are two very different verbs. "Er liebt wo er lebt." = "He loves where he lives." (16-20) SEPARABLE PREFIX VERBS Note, “separable prefix” verbs are ones that are expressed with a PREFIX (usually a preposition) that SEPARATES to the end of a clause when conjugated, but is a true prefix when given in the infinitive form (in dictionaries, for example). I underline the separable prefix. If a prefix (such as be-, ver-, zer-, ent-, is not underlined, then the prefix is never separated. (See # 21-25 ) Here are some common examples of separable prefix verbs: 5 16. kommen (an, aus, ein, be-) “Kommen“ is a verb meaning “to come,” but it also can be formed into many “separable prefix” verbs, all having different meanings. ankommen = to arrive; to “get” (somewhere) auskommen = to “manage” to “get by” einkommen = to come in (or...reinkommen - to come into a room or house) bekommen = to receive; to “get” (something) (It DOES NOT mean “to become”!!) 17. ziehen (aus, ein, um) “Ziehen“ is a verb meaning “to pull,” (you will see it on one side of doors in Germany – “drücken” is on the other side) but it also can be formed into many “separable prefix” verbs, all having different meanings. It also can mean “to move,” as in what you do with a playing piece on a board game. ausziehen = to move out; to undress anziehen = to put on (oneself); to dress einziehen = to move in umziehen = to “move” from one home to another 18. stellen (vor, aus, auf, ein) “Stellen“ is a verb meaning “to set up or stand something up,” (it’s similar to “legen” = to lay or “to put” something somewhere) but it also can be formed into many “separable prefix” verbs, all having different meanings. vorstellen = to introduce (someone), to present (sich vorstellen) = to imagine ausstellen = to exhibit, to display aufstellen = to put up, to post, to set up einstellen = to put in, to “stop” 19. steigen (ein, aus, um) “Steigen“ is a verb meaning “to climb,” but it also can be formed into many “separable prefix” verbs, all having different meanings and used frequently with modes of transportation. (You don’t “get in” a car or bus or train in German, you “climb in.”) einsteigen = to “get in” or “to get on” aussteigen = to “get out” or “to get off” umsteigen = to change (trains, planes, buses, etc) 20. nehmen, mitnehmen zunehmen, abnehmen, aufnehmen, herausnehmen, benehmen nehmen = to take (ahold) mitnehmen = to take along; to carry; to take with zunehmen = to increase; to grow (in number); to gain (as in weight); to “add to” abnehmen = to decrease; to lessen (in number); to lose (as in weight); to “take off” aufnehmen = to“take up“ i.e. “to begin; to “take” a recording, i.e. “to shoot” “record” herausnehmen = to “take (something) out“ benehmen = to behave; to “act” (not separable!) 6 (21-25) NON-SEPARABLE PREFIX VERBS - Prefixes such as be-. ver, emp, ent, zer... do not separate from the verb, but do change the meaning of the root verb. 21. sprechen ≠ besprechen ≠ versprechen sprechen = to speak; to talk besprechen = to discuss; to talk about versprechen = to promise 22. suchen ≠ besuchen ≠ versuchen suchen = to look for; to search besuchen = to visit versuchen = to try; to attempt 23. schreiben ≠ beschreiben ≠ verschreiben schreiben = to write beschreiben = to describe verschreiben = to prescribe 24. stehen ≠ bestehen ≠ verstehen stehen = to stand bestehen = to “pass” (a test); to “consist of” verstehen = to understand; to comprehend 25. fehlen, befehlen, empfehlen fehlen = to lack; to “be out/gone/away”; to “be needing” befehlen = to order; to command empfehlen = to recommend 26. To "TRY" (probieren ≠ versuchen) While both of these verbs mean "to try“ in English, they are used rather differently. “Probieren” is “to try on” to try out” “to taste (food for the first time).” For example, “Ich probiere das Auto.” = “I’m test-driving the car.” ,,Ich probiere das Essen.” = "I’m tasting the food.“ „Versuchen“ means "to attempt.“ „Ich versuche, den Ball ins Tor zu schießen.“ = "I try to shoot the ball into the goal.“ 27. To "BECOME" ≠ To "GET" / RECEIVE (werden ≠ bekommen) These two verbs perhaps cause more frequent confusion than any others in German for English speakers! “Werden” is a multi-purpose verb that, alone, means “to become.” Idiomatically, it can be translated other ways. “Ich werde fünfzehn.” = “I’m turning fifteen (years old)” “Ich werde Arzt.” = “I’m becoming (studying to be) a doctor.” "He's getting bigger." = "Er wird größer." “Werden” is also an AUXILIARY (helping verb) in expressing the FUTURE TENSE and PASSIVE VOICE. “Ich werde einen Hamburger essen.” = “I will eat a hamburger.” (future) “Ich werde gejubelt.” = “I’m getting cheered.” (passive) While the German "werden" means "to become" in English, the German verb "bekommen" is a FALSE COGNATE (a "cognate" is a similar word in two languages). "Bekommen" means to "get" or "receive" something. "I get good grades." = "Ich bekomme gute Noten." 7 28. To EAT (essen ≠ fressen) German makes distinctions that English doesn’t. This “Oklahoma” verb (stem vowel change e>I in the present - see #36) means “to eat.” “Essen” is only used with human beings. “Fressen” is only used with animals. "Mein Freund isst Pizza." = "My friend eats pizza." But "Meine Katze frisst Katzenfutter." = "My cat eats cat-food." 29. To LAY ≠ To LIE (legen ≠ liegen) The difference between these two verbs is exactly the difference between the English verbs "to lay“ and "to lie.“ (Somehow, many native English speakers never get a real good handle on those English verbs either!!) “Legen” (to lay) requires a direct object and is a dynamic (motion) verb. “I lay the book on the table.” = “Ich lege das Buch auf den Tisch.” "Liegen“ (to lie) does not take a direct object. It is static verb – shows a “state” – of what the subject is “being.” “The book lies (or – “is lying”) on the table.” = “Das Buch liegt auf dem Tisch.” "Liegen“ is also commonly used to express where something is located. „Café Julia liegt auf der Goethestraße.” = “Café Julia is on Goethestraße.” (Goethe-street) „Berlin liegt in Norddeutschland.“ = "Berlin’s located in Northern Germany.“ 30. To "TEACH" (unterrichten ≠ beibringen ≈ lehren) All three of these verbs have to do with "teaching“ but are different. “Unterrichten” is generally the verb used for the activity that teachers engage in in classrooms in schools and universities. It literally means “to instruct.” "beibringen" is "to teach" in the sense of "to show how to do" - this is often used reflexively when people teach themselves. "Ich habe mich selber beigebracht, Deutsch zu sprechen." = "I taught myself to speak German." Although "lehren" can mean "to teach" in a general sense - "Ich lehre Jugendlichen." = "I teach young people," this verb connotes more of "to impart teachings" or even "to lecture on learned things" and is not so much used in school classrooms these days, although "one who instructs, i.e. a 'teacher'" is still known as a "Lehrer." 31. To KILL ≠ To DIE (töten ≈ umbringen ≠ sterben ≈ um das Leben kommen) The verb “ töten“ is “ to kill“ in an active sense. The verb “ umbringen“ is used passively in more accidental circumstances. "Krankheiten bringen viele Leute in Afrika um." = "Diseases kill many people in Afrika." (lit: Diseases bring many people in Afrika around.) "Sterben" ( an "Oklahoma" verb) is "to die." "Der Jäger tötet den Hirsch; aber der Hirsch stirbt." = "The hunter kills the deer; but the deer dies." "Um das Leben kommen" (lit: around the life to come) is a way of saying "to die" when it's more accidental. "Viele Leute kommen um das Leben in Autounfälle jedes Jahr." = "Many people die in car accidents every year." 32. To "BE ABOUT" (sich handeln ≈ umgehen) Both of these verbs can mean “to be about…” In the context of this class I will tend to use “sich …handeln” more for the plot of stories, while “umgehen” I will apply to what is being focused upon, such as themes or specific events. For example, “Es handelt sich um ein Mädchen, die langes Haar hat“ = “It’s about a girl who has long hair.” Or “Es geht immer um sie.” = “It’s always about her.” Or „Es geht immer um Geld.“ = “It always has to do with money.” 8 33. To "FIGHT" (diskutieren – streiten - kämpfen) All three of these verbs can mean “to fight.” “Diskutieren” always means “to argue with words” (though it can also simply mean “to discuss,” like “besprechen”); “streiten” (can be reflexive) means “to fight” and may either be verbal or physical. “Kämpfen” may mean “to fight” but in a larger, more general sense. It’s more like a “prolonged struggle.” “Sie kämpfen für ihre Rechte.“ = “They’re fighting for their rights.“ “Kämpfen” may also refer to sport. 34. To "TAKE PLACE" (platznehmen ≠ stattfinden) Both of these verbs have to do with “taking a place.” “Platznehmen” is “to sit down” “to find a seat” “to take a seat.” “Stattfinden” is “to take place,” usually when describing the location for some work of fiction, be it a book, movie, story, etc. For example, Treffpunkt Berlin findet in Berlin statt. (Don’t confuse “statt“ with “Stadt“ – city – or “Staat“ – state) 35. –IEREN verbs telefonieren – spazieren – diskutieren – trainieren – photografieren – arrangieren – protestieren – globalisieren – aktualizieren – dramatisieren – etc. Verb infinitives ending in –ieren are have their roots in other non-Germanic languages such as Latin and Greek. These verbs are always regular and do not take the “ge- prefix” in forming the past participle. For example: “Er hat trainiert.” = “He trained ( or “practiced”).” 36. „Oklahoma“ Verbs This is a category of verb that has a VOWEL SHIFT in the STEM or ROOT (first or main part) of the verb in the PRESENT TENSE. This affects ONLY the 2ND AND 3RD PERSON SINGULAR. (du, er, sie) Why do I call it “Oklahoma.” Well, when you write out a twocolumn verb conjugation and draw a line around the other forms (ich, wir, ihr, sie) it sort of makes the shape of that state. Several vowel shifts can occur: e>ie, a>ä, e>i Examples of each are: ich sehe>er sieht, ich fahre>er fährt, ich spreche>er spricht. You learn about these in DA1 - Chapter 7. 37. Modal Verbs This is a category of verb that is used as "auxiliary" verbs. They "go along with" or "help" another verb. (However, the second verb is often merely implied and not even expressed!) The seven most common "Modal Verbs" (DA1 - Chapter 6) are mögen, müssen, wollen, dürfen, können, sollen and möchten. These verbs are EXTREMELY COMMON, so it pays to learn to use them quickly. Several of them change forms between the singular and plural in the present tense. Examples: Ich mag Deutsch lernen. I like to learn German. Wir mögen Deutsch lernen. We like to learn German. Ich muss Deutsch lernen. I have to learn German. Wir müssen Deutsch lernen. We have to learn German. Ich will Deutsch lernen. I want to learn German. Wir wollen Deutsch lernen. We want to learn German. Ich darf Deutsch lernen. I am allowed to learn German. Wir dürfen Deutsch lernen. We are allowed to learn German. Ich kann Deutsch lernen. I can learn German. Wir können Deutsch lernen. We can learn German. Ich soll Deutsch lernen. I should learn German. Wir sollen Deutsch lernen. We should learn German. Ich möchte Deutsch lernen. I would like to learn German. Wir möchten Deutsch lernen. We would like to learn German. 9 10

![D1A70204 Befehlformen [Command Forms] Commands (Befehle](http://s1.studylibde.com/store/data/006295093_1-ded304d13987e352eae01a2a5fa30f24-300x300.png)