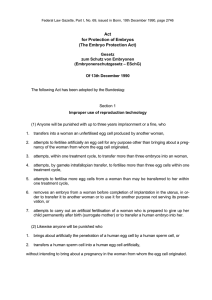

towards an international convention against human reproductive

Werbung