Logik und Mengentheorie

Werbung

Info IV: Logik und Mengentheorie

Michael Leuschel

2017

1 / 95

Was ist Logik?

• Quelle:

http://www.3sat.de/page/?source=/philosophie/159958/index.html:

2 / 95

Was ist Logik?

• Quelle:

http://www.3sat.de/page/?source=/philosophie/159958/index.html:

• Was fällt ihnen zu Logik ein? “Mr. Spock”, Gehirnjogging,

Frauenlogik und Männerlogik...

• Wir sagen “klingt logisch.” Wenn etwas vernünftig klingt.

• Und “hä? Das ist doch total unlogisch!”, wenn wir etwas nicht

verstehen.

• Aber Logik ist mehr. Viel mehr.

2 / 95

Was ist Logik?

• Quelle https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logik:

3 / 95

Was ist Logik?

• Quelle https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Logik:

• vernünftiges Schlussfolgern, Denklehre

• In der Logik wird die Struktur von Argumenten im Hinblick auf

ihre Gültigkeit untersucht, unabhängig vom Inhalt der

Aussagen

• Traditionell ist die Logik ein Teil der Philosophie.

• Seit dem 20. Jahrhundert versteht man unter Logik

überwiegend symbolische Logik, die auch als grundlegende

Strukturwissenschaft, z. B. innerhalb der Mathematik und der

theoretischen Informatik, behandelt wird.

3 / 95

Warum Logik studieren?

4 / 95

Warum Logik studieren?

• Hardware: logische Schaltkreise

• Wissensdarstellung und intelligentes Denken: künstliche

Intelligenz, deklarative Darstellung von Wissen, semantisches

Web, ...

• Überlegungen über Programme: Verifikation, statische

Programmanalyse, Programmoptimierung,...

• Universale Vorrichtung zur Berechnung: Datenbanken, logische

Programmierung, ...

4 / 95

Welche Logik studieren?

5 / 95

Welche Logik studieren?

• Aussagenlogik

• Prädikatenlogik der ersten Stufe (FOL)

• Logik höherer Stufe (HOL)

• eine temporale Logik

• eine mehrwertige Logik oder gar Fuzzy Logik

• Relevanzlogik, lineare Logik

• eine nichtmonotone Logik

Wir werden die klassische, zweiwertige, monotone Aussagenlogik

und Prädikatenlogik studieren (zusammen mit Mengentheorie).

5 / 95

Aussagenlogik

• eine Aussage identifizieren wir mit einem Bezeichner wie p

oder q

• eine Aussage ist entweder wahr (TRUE ) oder falsch (FALSE )

• die Logik interessiert sich weniger ob Aussagen wie p oder q

wahr oder falsch sind, sondern mehr um Zusammenhänge

zwischen möglichen Wahrheitswerten verschiedener Aussagen

und Formeln

6 / 95

Junktoren

• Aussagen können mit Junktoren zu Formeln verknüpft

werden:

• die Negation einer Aussage oder Formel p ist ¬p

• die Konjunktion von p und q ist p ∧ q

Intuitiv: sowohl p als auch q sind wahr

• die Disjunktion von p und q ist p ∨ q

Intuitiv: entweder p oder q (auch beide) sind wahr

• die Implikation von p nach q ist p ⇒ q

Intuitiv: wenn p wahr ist muss auch q wahr sein

• die Äquivalenz zwischen p und q ist p ⇔ q

Intuitiv: p und q haben den selben Wahrheitswert

7 / 95

Formale Definition einer Formel in Aussagenlogik

Sei gegeben eine Menge A an Aussagen. Die Menge FA der

Formeln in Aussagenlogik über A ist die kleinste Menge and

Formeln, so dass

• A ⊆ FA (jede Aussage ist auch eine Formel),

• wenn φ ∈ FA und ψ ∈ FA dann ist auch

• (¬φ) ∈ FA ,

• (φ ∧ ψ) ∈ FA ,

• (φ ∨ ψ) ∈ FA ,

• (φ ⇒ ψ) ∈ FA ,

• (φ ⇔ ψ) ∈ FA .

Anmerkung: wir werden später andere Arten der Definition von FA

sehen.

8 / 95

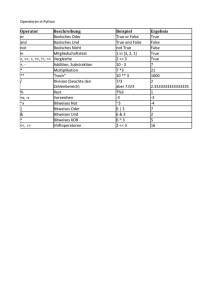

Prioritäten

Alle Formeln in FA sind komplett geklammert. Wir erlauben

alternative Schreibweisen, mit weniger oder mehr Klammern.

Ist je nach Buch, Vorlesung, Formalismus unterschiedlich. In der B

Sprache (mit der diese Folien erstellt wurden) haben wir:

• ¬ bindet am stärksten : ¬a ∧ b entspricht (¬a) ∧ b

• danach kommt ⇔ und ist links assoziativ:

a ⇔ b ⇔ c entspricht (a ⇔ b) ⇔ c

• ∧ and ∨ haben die gleiche Priorität und sind links assoziativ:

a ∧ b ∨ c entspricht (a ∧ b) ∨ c und

a ∨ b ∧ c entspricht (a ∨ b) ∧ c

• danach kommt ⇒ und ist links assoziativ:

a ⇒ b ⇒ c entspricht (a ⇒ b) ⇒ c

• im Zweifel lieber Klammern setzen !

Beispiel: d ⇔ a ∨ b ⇒ c ∧ d entspricht ((d ⇔ a) ∨ b) ⇒ (c ∧ d).

9 / 95

Beispiel: d ⇔ a ∨ b ⇒ c ∧ d entspricht ((d ⇔ a) ∨ b) ⇒ (c ∧ d).

=

true

d

<=>

false

d <=> a

=

false

a

or

true

d <=> a or b

=

true

b

&

true

c&d

=

true

c

=>

true

=

true

d

Im Zweifel lieber Klammern setzen !

10 / 95

Hardware Schaltung

• Aussage: Spannung an einem Punkt der Schaltung

• Welcher Formel in Aussagenlogik entspricht folgende

Schaltung?

11 / 95

Hardware Schaltung als Aussagenlogik Formel

• Formel für die Aussgabe e: (a ∨ b) ∧ c

• Formel für die gesamte Schaltung (mit Zwischenpunkten):

d ⇔ (a ∨ b) ∧ e ⇔ (c ∧ d )

• Frage: kann die Ausgabe e wahr werden? Wenn ja, für welche

Eingaben und Zwischenwerte? Wie kann einem die Logik dabei

helfen? d ⇔ (a ∨ b) ∧ e ⇔ (c ∧ d ) ∧ e

12 / 95

Interpretationen

• eine Interpretation i für eine Formel und eine Menge an

Aussagen A ist eine totale Funktion i ∈ A → {FALSE , TRUE }.

• Beispiel: eine mögliche Interpretation für p ∨ q ist

{p 7→ TRUE , q 7→ FALSE }.

• Insgesamt gibt es vier Interpretationen:

{p 7→ TRUE , q 7→ TRUE },{p 7→ TRUE , q 7→ FALSE },{p 7→

FALSE , q 7→ TRUE }, {p 7→ FALSE , q 7→ FALSE }.

13 / 95

Interpretation für Formeln

• gegeben eine Interpretation i ∈ A → {FALSE , TRUE }

• man kann damit den Wahrheitswert jeder Formel φ die

Aussagen in A benutzt berechnen:

• man berechnet den Wahrheitswert der Aussagen in φ mit i

• man berechnet den Wahrheitswert von immer grösseren

Unterformeln mit den Wahrheitstabellen der Junktoren

• Beispiel: gegeben i = {p 7→ TRUE , q 7→ FALSE } ist

i(p ∨ q) = TRUE , basierend auf der Tabelle für die

Disjunktion:

p

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

14 / 95

q

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p∨q

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

Wahrheitstabellen

• Beispiel: gegeben i = {p 7→ TRUE , q 7→ FALSE } ist

i(p ⇔ (p ∨ q)) = TRUE , basierend auf:

p

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

15 / 95

q

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

¬p

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

p∧q

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

p∨q

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

p⇒q

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p⇔q

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

Modelle

• eine Interpretation i so dass i(φ) = TRUE ist ein Modell für φ

• eine Formel φ die mindestens ein Modell hat heißt erfüllbar

• eine Formel φ wo alle Interpretationen auch Modelle sind wird

eine Tautologie genannt

• eine Formel ohne Modell heißt unerfüllbar oder ein

Widerspruch

p

FALSE

TRUE

16 / 95

¬p

TRUE

FALSE

p ∨ ¬p

TRUE

TRUE

p ∧ (¬p)

FALSE

FALSE

p ⇒ ¬p

TRUE

FALSE

Beispiel

φ = p ∨ (q ∧ r )

p

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

17 / 95

q

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

r

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

phi

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

Goldene Regel

Folgende Formel kommt aus dem Buch “A logical approach to

discrete math” von Gries und Schneider: φ =

(p ∧ q) ⇔ p ⇔ q ⇔ (p ∨ q).

Dies ist eine Tautologie:

p

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

18 / 95

q

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p∧q

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

p∧q ⇔p

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

(p ∧ q ⇔ p) ⇔ q

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

φ

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

Modelle für Hardware Beispiel

• Frage: kann die Ausgabe e wahr werden?

• Entspricht der Frage: ist folgende Formel φ erfüllbar:

d ⇔ (a ∨ b) ∧ e ⇔ (c ∧ d ) ∧ e

Dies sind all Modelle von φ:

a

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

19 / 95

b

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

c

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

d

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

e

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

Modell für Hardware Beispiel

Dies ist ein Modell von d ⇔ (a ∨ b) ∧ e ⇔ (c ∧ d ) ∧ e als

Formelbaum:

=

true

d

=

false

a

<=>

true

d <=> (a or b)

or

true

a or b

=

true

b

&

true

<=>

true

e <=> (c & d)

=

true

e

=

true

e

&

true

c&d

=

true

c

=

true

d

20 / 95

Äquivalenz von Formeln

Zwei Formeln sind äquivalent gdw sie die selben Modelle haben.

p

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

q

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p⇒q

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p ∨ (¬q)

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

(¬p) ∨ q

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p ⇒ q und (¬p) ∨ q sind äquivalent. Wir schreiben dies auch als

p ⇒ q ≡ (¬p) ∨ q.

Anmerkung (p ⇒ q) ⇔ ((¬p) ∨ q) ist eine Tautologie.

21 / 95

Wichtige Äquivalenzen

Für alle Formeln φ, ψ gilt:

• φ ⇒ ψ ≡ (¬φ) ∨ ψ

• φ ⇔ ψ ≡ (φ ⇒ ψ) ∧ (ψ ⇒ φ)

• ¬¬φ ≡ φ

• ¬(φ ∧ ψ) ≡ (¬φ) ∨ (¬ψ)

• ¬(φ ∨ ψ) ≡ (¬φ) ∧ (¬ψ)

• φ∧ψ ≡ψ∧φ

• φ∨ψ ≡ψ∨φ

22 / 95

Kontraposition

¬ψ ⇒ ¬φ ist die Kontraposition von φ ⇒ ψ. Ist diese Form

äquivalent? Zur Prüfung kann man die komplette Wahrheitstabelle

aufbauen, mit allen möglichen Werten für die offenen Formeln φ, ψ:

p

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

23 / 95

q

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p⇒q

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

¬q ⇒ ¬p

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Logisches Schließen von Formeln

• Wenn p ∧ q gilt, dann ist p eine logische Konsequenz

(Schlussfolgerung) von p ∧ q.

• Wir schreiben dies als p ∧ q |= p

• Formal bedeutet dies, dass alle Modelle von q ∧ p auch

Modelle von p sind.

• Die Tabelle zeigt, dass p ⇔ q |= p ⇒ q. Die Formeln sind

nicht äquivalent.

p

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

24 / 95

q

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

p⇔q

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

p⇒q

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Wichtige logische Schlussfolgerungen

Für alle Formeln φ, ψ gilt:

• φ ∧ ψ |= φ

• (φ ⇒ ψ) ∧ φ |= ψ (Modus Ponens)

• (φ ⇒ ψ) ∧ ¬ψ |= ¬φ (Modus Tollens)

• (φ ⇔ ψ) ∧ ψ |= φ

• (φ ⇔ ψ) ∧ ¬ψ |= ¬φ

• Achtung φ ∧ ¬φ |= ψ für beliebiges ψ !

25 / 95

Smullyan - Einfaches Puzzle

Raymond Smullyan beschreibt in seinen Büchern eine Insel auf der

es zwei Arten von Personen gibt:

• Ritter die immer die Wahrheit sagen, und

• Schurken die immer lügen.

26 / 95

1

X sagt: “Y ist ein Ritter”

2

Y sagt: “X und ich sind von einem unterschiedlichen Typ.”

Smullyan - Einfaches Puzzle

1

X sagt: “Y ist ein Ritter”

X ⇔Y

2

Y sagt: “X und ich sind von einem unterschiedlichen Typ.”

Y ⇔ (X ⇔ ¬(Y ))

X

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

27 / 95

Y

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Satz1

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

Satz2

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

Puzzle

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

Smullyan - Tiger und Prinzessin Puzzle (3)

Puzzle aus “The Lady or the Tiger” von Raymond Smullyan.

• Hinter jeder Kerkertür gibt es entweder ein Tiger (der einen

sofort auffrisst) oder eine Prinzessin (und man ist frei)

• In diesem Puzzle gibt es zwei Türen mit jeweils einem Zettel

• Entweder sagen beide Zettel die Wahrheit oder beide sind

falsch

• Zettel auf Tür 1: Es ist ein Tiger hinter dieser Tür oder eine

Prinzessin hinter der anderen Tür

• Zettel auf Tür 2: Hinter der anderen Tür befindet sich eine

Prinzessin

Soll der Gefangene eine Tür aufmachen? Wenn ja, welche?

28 / 95

Smullyan - Tiger und Prinzessin Puzzle (3) - Lösung

• Entweder sagen beide Zettel die Wahrheit oder beide sind

falsch

φ = Z1 ⇔ Z2

• Tür 1: Es ist ein Tiger hinter dieser Tür oder eine Prinzessin

hinter der anderen Tür

Z 1 = T1 ∨ ¬(T2 )

• Tür 2: Hinter der anderen Tür befindet sich eine Prinzessin

Z 2 = ¬(T1 )

• φ |= ¬T 1 ∧ ¬T 2 (man kann beide Türen aufmachen)

T1

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

29 / 95

T2

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Z1

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

Z2

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

Phi

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

Smullyan - Tiger und Prinzessin Puzzle (6)

• Hinter jeder Kerkertür gibt es entweder ein Tiger (der einen

sofort auffrisst) oder eine Prinzessin (und man ist frei)

• In diesem Puzzle gibt es zwei Türen mit jeweils einem Zettel

• Zettel 1 sagt die Wahrheit gdw eine Prinzessin hinter der Tür

ist

• Zettel 2 sagt die Wahrheit gdw ein Tiger hinter der Tür ist

• Zettel auf Tür 1: Wähle eine der beiden Türen; es macht

keinen Unterschied.

• Zettel auf Tür 2: Hinter der anderen Tür befindet sich eine

Prinzessin

Soll der Gefangene eine Tür aufmachen? Wenn ja, welche?

30 / 95

Smullyan - Tiger und Prinzessin Puzzle (6) - Lösung

• Zettel 1 (2) sagt die Wahrheit gdw eine Prinzessin (Tiger)

hinter der Tür ist

φ = Z1 ⇔ ¬(T1 ) ∧ Z2 ⇔ T2

• Tür 1: Wähle eine der beiden Türen; es macht keinen

Unterschied

Z 1 = T1 ⇔ T2

• Tür 2: Hinter der anderen Tür befindet sich eine Prinzessin

Z 2 = ¬(T1 )

• φ |= T 1 ∧ ¬T 2 (Tür 2 aufmachen)

T1

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

31 / 95

T2

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Z1

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

Z2

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

Phi

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

Deduktiver Beweis

1

φ1

2

φ2

3

...

4

φk

wo immer gilt φ1 ∧ ...φi |= φi+1 .

Wir haben per Transitivität von |=, dass φ1 |= φk .

32 / 95

Deduktiver Beweis (Beispiel)

Kleines anderes Insel-Puzzle:

1

φ1 =

A ⇔ B ∧ (A sagt: “B ist ein Ritter”)

B ⇔ ⊥ (B sagt: “1+1=3”)

2

¬B (nach der zweiten Aussage muss B ein Schurke sein)

3

¬A (nach der ersten Aussage muss A demnach auch ein Schurke sein)

Wir haben per Transitivität von |=, dass φ1 |= ¬A.

(φ1 |= φ1 ∧ ¬B |= ¬A)

33 / 95

Äquivalenzbeweis

Hier schreiben wir in der Regeln in folgender Form:

1

φ1

2

⇐⇒ φ2

3

...

4

⇐⇒ φk

wo immer gilt φi ≡ φi+1 .

Wir haben per Transitivität von ≡, dass φ1 ≡ φk .

Kleines Beispiel, beweise, dass ¬b ⇒ a ≡ a ∨ b:

34 / 95

1

¬b ⇒ a

2

⇐⇒ ¬¬b ∨ a (Regel: φ ⇒ ψ ≡ ¬φ ∨ ψ)

3

⇐⇒ b ∨ a (Regel: ¬¬φ ≡ φ))

4

⇐⇒ a ∨ b (Kommutativität von ∨)

Beweis durch Widerspruch

• Theorem: φ |= ψ genau dann wenn φ ∧ ¬ψ kein Modell hat

Beweis (ist ein Äquivalenzbeweis auf Metaebene):

• φ |= ψ

• ⇐⇒ alle Modelle von φ sind auch Modelle von ψ (per

Definition von |=)

• ⇐⇒ in allen Modellen von φ hat ¬ψ den Wahrheitswert falsch

(per Definition von ¬)

• ⇐⇒ alle Modelle von φ sind kein Modell von φ ∧ ¬ψ (per

Definition von ∧)

• ⇐⇒ φ ∧ ¬ψ hat kein Modell (da auch kein Modell von ¬φ ein

Modell von φ ∧ ¬ψ sein kann)

35 / 95

Smullyan Arthur York - Inspektor Craig Puzzle

• Knights (Ritter): sagen immer die Wahrheit, Knaves

(Schurken): lügen immer

• Arthur York wird von Inspektor Craig gesucht und ist ein Ritter

oder Schurke, der Angeklagte ist auch ein Ritter oder Schurke.

• Auszug aus "To Mock a Mockingbird, Raymond

Smullyan"(Seite 41, The First Trial).

•

•

•

•

Craig: What do you know about Arthur York

Angeklagter: Arthur York once claimed that I was a knave.

Craig: Are you by any chance Arthur York?

Angeklagter: Yes

Folgt aus dieser logischen Theorie, dass der Angeklagte Arthur York

ist?

36 / 95

Smullyan Puzzle: Lösung

• Aussage YR ist wahr wenn Arthur York ein Ritter ist,

• Aussage Schuldig ist wahr wenn der Angeklagte Arthur York

ist,

• Aussage AR ist wahr wenn der Angeklagte ein Ritter ist.

• Wir wissen auch (φ1 ) Schuldig ⇒ YR ⇔ AR

• Angeklagter: Arthur York once claimed that I was a knave

(φ2 ): AR ⇒ YR ⇔ ¬(AR)

• Craig: Are you by any chance Arthur York? Angeklagter: Yes

(φ3 ): AR ⇔ Schuldig

Die Konjunktion φ = φ1 ∧ φ2 ∧ φ3 dieser Formeln hat nur zwei

Modelle, wir haben φ |= ¬Schuldig :

YR

FALSE

TRUE

37 / 95

Schuldig

FALSE

FALSE

AR

FALSE

FALSE

Smullyan Puzzle: Lösung

• (φ1 ) Schuldig ⇒ YR ⇔ AR

• (φ2 ): AR ⇒ YR ⇔ ¬(AR)

• (φ3 ): AR ⇔ Schuldig

Die Konjunktion φ hat nur zwei Modelle, wir haben φ |= ¬Schuldig :

YR

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

38 / 95

Schuldig

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

AR

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Phi1

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

Phi2

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

Phi3

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

Phi

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

FALSE

Smullyan Puzzle: Beweis durch Widerspruch

• unsere Theorie: φ = Schuldig ⇒ YR ⇔ AR ∧

AR ⇒ YR ⇔ ¬(AR) ∧ AR ⇔ Schuldig

• um zu Beweisen dass φ |= ¬Schuldig gilt

• negieren wir was wir beweisen wollen: ¬¬Schuldig = Schuldig

•

•

•

•

•

(auf Deutsch: nehmen wir an der Angeklagte ist Arthur York)

fügen dies zur Theorie hinzu: φ ∧ Schuldig

und zeigen, dass dies ein Widerspruch ist (kein Modell hat)

d.h., in allen Modellen von φ ist Schuldig falsch

d.h., in allen Modellen von φ ist ¬Schuldig wahr

d.h., wir haben bewiesen, dass φ |= ¬Schuldig

• (siehe unser Theorem: φ |= ψ genau dann wenn φ ∧ ¬ψ kein

Modell hat)

39 / 95

Smullyan Puzzle: Beweis durch Widerspruch im Detail

40 / 95

1

(φ ⇔ ψ) ∧ ψ |= φ

2

Schuldig ⇒ YR ⇔ AR

3

AR ⇒ YR ⇔ ¬(AR)

4

AR ⇔ Schuldig

5

Schuldig (Nehmen wir an der Angeklagte ist Arthur York)

6

Aus 4 und 5 (und Regel 1) folgt: AR (der Angeklagte ist ein Ritter)

7

Aus 6 und 3, folgt durch die Modus Ponens Regel dass:

(YR ⇔ ¬AR) (Arthur York once claimed that I was a knave)

8

Aus 7 und 6 folgt: ¬YR (Arthur York ist ein Schurke)

9

Aus 2 und 5 folgt: YR ⇔ AR,

10

Aus 9 und 8 folgt: ¬AR (der Angeklagte ist ein Schurke)

11

Die Aussagen 6 und 10 sind im Widerspruch, der Angeklagte

ist nicht schuldig.

Modell in der formalen Sprache Event-B

Anmerkung: in B/Event-B müssen Aussagen wie AR durch eine Bool’sche

Variable modelliert werden. Die Aussage AR entspricht AR = TRUE in B,

¬AR entspricht entweder AR = FALSE , AR 6= TRUE oder ¬(AR = TRUE ).

Die Symbole = und 6= stehen hier für Prädikate (sehen wir später).

41 / 95

Beweisobligation (Proof Obligation auf Englisch)

Dies ist die aus dem Modell generierte Beweisobligation:

φ1 ∧ φ2 ∧ φ3 |= ¬Schuldig :

Der Beweis auf der nächste Folie ist sehr ähnlich zu unserem

Beweis, man sieht, dass AR und ¬AR abgeleitet wurden.

42 / 95

Beweis in der formalen Sprache Event-B

43 / 95

Graph-Färbung

Gegeben zwei Farben (Rot und Grün) sollen die Knoten in

folgendem Graphen g so eingefärbt werden, dass Nachbarn

unterschiedliche Farben haben:

"c"

gg

"b"

gg

"a"

Wie kann man dies Problem in Aussagenlogik lösen?

44 / 95

Modelle für Graph-Färbung

• Aussage ar : Knoten a ist rot gefärbt, Aussage ag : Knoten a ist

grün gefärbt, Aussage br : Knoten b ist rot gefärbt, ...

• ar ⇔ ¬(ag ) sagt aus, dass wir für a entweder rot oder grün

wählen müssen

• ar ⇒ ¬(br ) sagt aus, dass a und b nicht gleichzeitig rot sein

dürfen

• Dies sind alle Modelle von

(ar ⇒ ¬(br )) ∧ (ag ⇒ ¬(bg )) ∧ (br ⇒ ¬(cr )) ∧ (bg ⇒

¬(cg )) ∧ ar ⇔ ¬(ag ) ∧ br ⇔ ¬(bg ) ∧ cr ⇔ ¬(cg ):

ar

FALSE

TRUE

45 / 95

br

TRUE

FALSE

cr

FALSE

TRUE

ag

TRUE

FALSE

bg

FALSE

TRUE

cg

TRUE

FALSE

Modell für Graph-Färbung

Dies ist ein Modell von (ar ⇒ ¬(br )) ∧ (ag ⇒ ¬(bg )) ∧ (br ⇒

¬(cr )) ∧ (bg ⇒ ¬(cg )) ∧ ar ⇔ ¬(ag ) ∧ br ⇔ ¬(bg ) ∧ cr ⇔ ¬(cg )

als Formelbaum:

=

false

br

=

true

cr

not

false

not(cr)

not

true

not(br)

=

false

br

=

true

ar

=>

true

br => not(cr)

=>

true

ar => not(br)

=

true

bg

=

false

cg

not

true

not(cg)

not

false

not(bg)

=>

true

bg => not(cg)

&

true

<=>

true

ar <=> not(ag)

not

true

not(ag)

=

true

cr

<=>

true

cr <=> not(cg)

=>

true

ag => not(bg)

=

false

ag

<=>

true

br <=> not(bg)

=

false

br

=

true

ar

=

false

ag

not

true

not(cg)

not

false

not(bg)

=

true

bg

=

false

cg

46 / 95

=

true

bg

Auf zur Prädikatenlogik und Mengentheorie

• man kann mit Aussagenlogik viel tun

• SAT-Solver skalieren erstaunlich gut

• Kodierung grösserer Probleme ist für den Menschen nicht mehr

lesbar: (ar ⇒ ¬(br )) ∧ (ag ⇒ ¬(bg )) ∧ (br ⇒ ¬(cr )) ∧ (bg ⇒

¬(cg )) ∧ ar ⇔ ¬(ag ) ∧ br ⇔ ¬(bg ) ∧ cr ⇔ ¬(cg )

• in Prädikatenlogik und Mengentheorie kann man das

Graphfärbungsproblem für einen beliebigen Graphen gr und

zwei Farben so ausdrücken:

col ∈ V → {red , green}

∀(x, y ).(x 7→ y ∈ gr ⇒ col (x) 6= col (y ))

47 / 95

Färbung mit Prädikatenlogik - 60 Knoten, 400 Kanten

Man kann auch versuchen die minimale Anzahl an Farben zu finden:

34

custom

12

custom

52

custom

custom

custom

custom

22

custom

custom

custom

custom

57

20

custom

custom

custom

8

custom

custom

6

custom

27

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

21

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

31

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

30custom

custom

custom

custom40 custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

25

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

32

custom

13

custom

14

custom

54

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

9

custom

5

48 / 95

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

56

custom

custom

custom custom

18

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

58

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

26

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom

custom custom

customcustom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

38

custom

50

custom

custom custom

custom custom

custom

1

custom

custom

43

3

custom custom 44

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom custom custom

custom

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom custom

17

custom

custom

custom

51

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

42

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom custom

11

custom

custom

custom

36

custom custom

custom custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom16

custom custom

4

28

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom custom

custom

48

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

19

custom

custom

custom

customcustomcustom

custom

custom custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom custom

24

37

custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

53

custom 2

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom customcustom

custom

custom

custom 49

custom

custom

60

41

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom

35

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

47

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

23

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

15

custom

10

33

custom

custom

customcustomcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom

59

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

46

custom

45

custom

custom custom

29

7

39

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

customcustom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

55

Färbung mit Prädikatenlogik - Lösung mit ProB

Man kann auch versuchen die minimale Anzahl an Farben zu finden:

34

custom

12

custom

52

custom

custom

custom

custom

22

custom

custom

custom

custom

57

20

custom

custom

custom

8

custom

custom

6

custom

27

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

21

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

31

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

30custom

custom

custom

custom40 custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

25

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

32

custom

13

custom

14

custom

54

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

9

custom

5

49 / 95

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

56

custom

custom

custom custom

18

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

58

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

26

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom

custom custom

customcustom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

38

custom

50

custom

custom custom

custom custom

custom

1

custom

custom

43

3

custom custom 44

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom custom custom

custom

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom custom

17

custom

custom

custom

51

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

42

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom custom

11

custom

custom

custom

36

custom custom

custom custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom16

custom custom

4

28

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom custom

custom

48

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

19

custom

custom

custom

customcustomcustom

custom

custom custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom custom

24

37

custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

53

custom 2

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom customcustom

custom

custom

custom 49

custom

custom

60

41

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

customcustom

35

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

47

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

23

custom

customcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

15

custom

10

33

custom

custom

customcustomcustom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

custom custom

custom

59

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

46

custom

45

custom

custom custom

29

7

39

custom

custom custom

custom

custom

customcustom custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom

custom custom

custom

55

Aristoteles: Anfänge der Logik

Syllogistik, einer Vorform der Prädikatenlogik

1

Alle Menschen sind sterblich.

2

Einige Menschen sind sterblich.

3

Alle Menschen sind unsterblich.

4

Einige Menschen sind unsterblich.

Zusammenhang unter der Annahme, daß es mindestens einen

Mensch gibt. (In die Aussagenlogik sind alle vier Aussagen

unabhängig.)

50 / 95

Aristoteles: Anfänge der Logik

Syllogistik, einer Vorform der Prädikatenlogik

1

Alle Menschen sind sterblich.

2

Einige Menschen sind sterblich.

3

Alle Menschen sind unsterblich.

4

Einige Menschen sind unsterblich.

Zusammenhang unter der Annahme, daß es mindestens einen

Mensch gibt. (In die Aussagenlogik sind alle vier Aussagen

unabhängig.)

• (1) |= (2), (3) |= (4)

• (1) ≡ ¬(4), (3) ≡ ¬(2)

• |= ¬((1) ∧ (3))

50 / 95

Prädikatenlogik

Im Vergleich zur Aussagenlogik mit den Wahrheitswerten

(TRUE ,FALSE ) und Aussagen, gibt es in der Prädikatenlogik:

• Objekte

• Konstanten und Variablen die Objekte darstellen,

• Funktionen die Objekte auf Objekte abbilden,

• Prädikate die Objekte oder Objekt-kombinationen auf einen

Wahrheitswert abbilden,

• Quantoren mit denen man Variablen einführt und Aussagen

über alle Objekte machen kann, oder die Existenz eines

Objekts zusichert

51 / 95

Prädikate

• “der Knoten a ist rot gefärbt” ist für ein bekanntes a eine

Aussage: sie ist entweder wahr oder falsch

• “die Farbe des Knotens a” ist keine Aussage: der Satz ist nicht

wahr oder falsch, sondern stellt ein Objekt dar

• “2+2 < 5” ist eine Aussage

• “x < 5” falls der Wert von x nicht bestimmt ist, ist dies keine

Aussage, der Wahrheitswert hängt von dem Wert der Variable

x ab

• “x < 5” ist ein Prädikat, für jeden möglichen Wert von x

können wir bestimmen ob das Prädikat wahr oder falsch ist

• Prädikate sind parametrisierte Aussagen

52 / 95

Prädikate

• LT 5(x) ≡ x < 5 ist ein unäres Prädikat, für jeden möglichen

Wert von x können wir bestimmen ob das Prädikat wahr oder

falsch ist, grafisch :

7

6

LT5 LT5

5

4

LT5

3

2

LT5 LT5 LT5

FALSE

1

LT5

TRUE

• < ist ein binäres Prädikat, für jede Kombination an Werten

können wir bestimmen ob das Prädikat wahr oder falsch ist:

x

1

1

2

2

53 / 95

y

1

2

1

2

x <y

FALSE

TRUE

FALSE

FALSE

freie Variablen

Die Formel x < 5 besteht formal gesehen aus:

• einer logischen Variable x,

• der Konstante 5 die für die Zahl 5 steht,

• dem binären Prädikatensymbol <, hier in Infix-Notation, mit

zwei Argumenten: x und 5.

• (In Präfix-Notation würde man < (x, 5) schreiben.)

Innerhalb von x < 5 ist x eine freie Variable.

In einer geschlossenen Formel der Prädikatenlogik müssen alle

Variablen durch Quantoren gebunden werden.

54 / 95

Quantoren

Es gibt zwei Quantoren:

• den Existenzquantor ∃

∃x.P, bedeutet, dass es ein Objekt o gibt, so dass wenn man x

durch o in P ersetzt die Formel wahr ist

• den Allquantor ∀

∀x.P bedeutet dass die Formel P für alle möglichen

Ersetzungen von x durch ein Objekt o wahr ist

• ∃x.x < 5 ist eine geschlossene Formel (aka eine Aussage). Mit

der Standardinterpretation von < und 5 ist diese Formel wahr;

eine Lösung ist x = 4.

• ∀x.x < 5 ist auch eine geschlossene Formel. Mit der

Standardinterpretation von < und 5 ist diese Formel falsch.

Ein Gegenbeispiel ist x = 5.

55 / 95

Logische Äquivalenz, Schlussfolgerung

Zwei Formeln φ und ψ sind äquivalent gdw sie die selben Modelle

haben. Wir schreiben dies als φ ≡ ψ.

Eine Formel ψ ist eine logische Schlussfolgerung von φ, wenn alle

Modelle von φ auch Modelle von ψ sind. Wir schreiben dies als

φ |= ψ.

Dies ist die gleiche Definition wie bei Aussagenlogik, nur das

Konzept der Modelle ist komplizierter:

• eine Menge an Objekten muss ausgewählt werden

• die Konstanten und Funktionen müssen den Objekten

zugeordnet werden

• die Prädikate müssen Objekte auf Wahrheitswerte abbilden;

Aussagen sind ein Spezialfall von Prädikaten.

• (manchmal sind bestimmte Symbole vordefiniert, wie <, +

oder 5)

56 / 95

Quantoren: Gesetze

Welche dieser Gesetze sind richtig? Beispiele?

57 / 95

1

¬∃x.P ≡ ∀x.¬P ?

2

¬∀x.P ≡ ∃x.¬P ?

3

∀x.(∀y .P) ≡ ∀y .(∀x.P) ?

4

∀x.(∃y .P) ≡ ∃y .(∀x.P) ?

5

∃x.(∃y .P) ≡ ∃y .(∃x.P) ?

Quantoren: Gesetze

58 / 95

1

¬∃x.P ≡ ∀x.¬P

¬∃x.(x > 0 ∧ x < 0) ≡ ∀x.¬(x > 0 ∧ x < 0) ≡

∀x.(x ≤ 0 ∨ x ≥ 0)

2

¬∀x.P ≡ ∃x.¬P

3

∀x.(∀y .P) ≡ ∀y .(∀x.P)

∀x.(∀y .(x ≤ y ∨ x > y )) ≡ ∀y .(∀x.(x ≤ y ∨ x > y ))

4

∀x.(∃y .P) 6≡ ∃y .(∀x.P)

∀x.(∃y .(y > x)) 6≡ ∃y .(∀x.(y > x)

5

∃x.(∃y .P) ≡ ∃y .(∃x.P)

Funktionen, Terme und Formeln

In der Formel x + 1 > 5 steht + für eine Funktion die Objekte auf

Objekte abbildet.

• Terme stehen für Objekte und sind Konstanten, Variablen

oder Funktionssymbole angewandt auf Terme.

• Formeln sind Aussagen, Prädikate angewandt auf Terme,

Formeln verknüpft mit Junktoren (∧, ∨, ...) oder Quantoren.

• x + 1 ist ein Term

• x + 1 > 5 ist eine Formel mit freien Variablen

• ∃x.x + 1 > 5 ist eine wohl-geformte Formel (ohne freie

Variablen)

59 / 95

Werkzeuge für Logik

• SAT Solver: Erfüllbarkeit von Aussagenlogik prüfen (miniSAT,

glucose, lingeling, Sat4j,...)

• SMT Solver: Erfüllbarkeit von Prädikatenlogik mit Theorien

(Bit-Vektoren,...): Z3 von Microsoft

• Beweiser: Atelier-B, Rodin, Isabelle, Coq, Vampire,...

• Model-Finder, Constraint Solver: ProB, Alloy, IDP, ...

• Programmiersprache: Prolog

• Hardware Verifikation

• schwere Probleme lösen (Eclipse/Linux Abhängigkeiten,...)

• Software Verifikation, Fehler finden (NullPointer Exception,

Overflows), Windows Driver Verification (SLAM2,...)

• Stellwerkprüfung (Prover Technologies, ...)

• Datenvalidierung (ProB bei Siemens, Alstom, Thales; Paris L1)

• Software Entwicklung (AtelierB, Paris L14, L1, ....: seit 1999

kein einziger Bug !)

60 / 95

Andere Logiken

• Aussagenlogik und Prädikatenlogik sind klassische zweiwertige

Logiken

• sie sind monoton wenn φ |= ψ dann gilt für alle ρ: φ ∧ ρ |= ψ

• Aussagenlogik ist entscheidbar

• Prädikatenlogik ist semi-entscheidbar: wenn φ |= ψ kann man

einen Beweis finden (Gödelscher Vollständigkeitssatz)

• reine Prädikatenlogik ist nicht ausreichend um Arithmetik zu

axiomatisieren (Gödelscher Unvollständigkeitssatz)

• es gibt Intuitionistische Logik: Beweis durch Widerspruch dort

nicht erlaubt

• es gibt dreiwertige Logiken ( 2/0 = 1 ∧ 1 = 2 )

• es gibt die Fuzzy Logik, modale Logiken, temporale Logiken,...

• nicht-monotone Logiken

61 / 95

Zusammenfassung Logik

• Aussagenlogik und Prädikatenlogik

• Interpretation, Modell, Äquivalenz (≡), logisches Schließen

(|=)

• Deduktiver Beweis, Äquivalenzbeweis

• Beweis durch Widerspruch

• Äquivalenzen (Kommutativität, de Morgan, ...)

• logische Formeln verstehen und erstellen können

62 / 95

Mengen

• Fundamentale Idee der Mengentheorie: "The ability to regard

any collection of objects as a single entity (i.e., as a

set)."(Keith Devlin. Joy of Sets.)

• wenn a ein Objekt ist und x eine Menge, dann

• ist a ∈ x wahr, wenn a ein Element von x ist

• ist a 6∈ x wahr, wenn a kein Element von x ist.

• ∈ und 6∈ sind Prädikate, mit der Eigenschaft:

∀(a, x).(a 6∈ x ⇔ ¬(a ∈ x))

• die leere Menge ∅ hat keine Elemente:

z = ∅ ⇔ ∀(a).(a 6∈ z)

63 / 95

Vereinigung, Schnitt, Differenz

• Vereinigung von Mengen ∪ :

z = x ∪ y ⇔ ∀(a).(a ∈ z ⇔ (a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ y ))

• {2, 3, 5} ∪ {5, 7} = {2, 3, 5, 7}

• Schnitt von Mengen ∩:

z = x ∩ y ⇔ ∀(a).(a ∈ z ⇔ (a ∈ x ∧ a ∈ y ))

• {2, 3, 5} ∩ {5, 7} = {5}

• Differenz von Mengen \:

z = x \ y ⇔ ∀(a).(a ∈ z ⇔ (a ∈ x ∧ a 6∈ y ))

• {2, 3, 5} − {5, 7} = {2, 3}

64 / 95

Notationen für Mengen: endliche Enumeration

• explizite Auflistung aller Elemente {a1 , . . . , an }

• die Reihenfolge spielt keine Rolle

• {2, 5, 3} = {2, 3, 5}

• Elemente können mehrfach auftauchen

• {2, 5, 3, 2, 5} = {2, 3, 5}

65 / 95

Notationen für Mengen: per Prädikat

• Definition der Elemente durch ein Prädikat {a | P(a)}

z = {a | P(a)} ⇔ ∀(a).(a ∈ z ≡ P(a))

• {a|a > 1 ∧ a < 6 ∧ a 6= 4} = {2, 3, 5}

• Man kann unendliche Mengen ausdrücken:

{a|a > 10}

• Andere Beispiele:

x ∪ y = {a | a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ y }

x ∩ y = {a | a ∈ x ∧ a ∈ y }

x \ y = {a | a ∈ x ∧ a 6∈ y }

Als Kürzel führen wir auch die Notation a..b für

{x | x ≥ a ∧ x ≤ b} ein.

66 / 95

Ein Theorem

Für alle Mengen x, y , z gilt:

• x ∪ (y ∩ z) = (x ∪ y ) ∩ (x ∪ z)

Beispiel:

• {2, 3, 5} ∪ ({2, 4, 7} ∩ {2, 4, 6}) = {2, 3, 4, 5}

• ({2, 3, 5} ∪ {2, 4, 7}) ∩ ({2, 3, 5} ∪ {2, 4, 6}) = {2, 3, 4, 5}

x

y

67 / 95

z

Beweis von x ∪ (y ∩ z) = (x ∪ y ) ∩ (x ∪ z)

Lemmata:

1 x ∪ y = {a | a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ y }

2 x ∩ y = {a | a ∈ x ∧ a ∈ y }

3 a ∈ {b | P(b)} ≡ P(a)

4 φ ∨ (ψ ∧ ρ) ≡ (φ ∨ ψ) ∧ (φ ∨ ρ)

Äquivalenzbeweis

1 x ∪ (y ∩ z)

2 (Lemma 1) ⇐⇒ {a | a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ (y ∩ z)}

3 (Lemma 2) ⇐⇒ {a | a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ {b | b ∈ y ∧ b ∈ z}}

4 (Lemma 3) ⇐⇒ {a | a ∈ x ∨ (a ∈ y ∧ a ∈ z)}

5 (Lemma 4) ⇐⇒ {a | (a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ y ) ∧ (a ∈ x ∨ a ∈ z)}

6 (Lemma 3, ⇐) ⇐⇒

{a | a ∈ {b | b ∈ x ∨ b ∈ y } ∧ a ∈ {b | b ∈ x ∨ b ∈ z}}

7 (Lemma 1, ⇐) ⇐⇒ {a | a ∈ x ∪ y ∧ a ∈ x ∪ z)}

8 (Lemma 2, ⇐) (x ∪ y ) ∩ (x ∪ z)

68 / 95

Gesetze

Für alle Mengen x, y , z gilt:

• x ∪ y = y ∪ x (Kommutativ 1)

• x ∩ y = y ∩ x (Kommutativ 2)

• x ∪ (y ∪ z) = (x ∪ y ) ∪ z (Assoziativ 1)

• x ∩ (y ∩ z) = (x ∩ y ) ∩ z (Assoziativ 2)

• x ∪ (y ∩ z) = (x ∪ y ) ∩ (x ∪ z) (Distributiv 1)

• x ∩ (y ∪ z) = (x ∩ y ) ∪ (x ∩ z) (Distributiv 2)

• z \ (x ∪ y ) = (z \ x) ∩ (z \ y ) (De Morgan 1)

• z \ (x ∩ y ) = (z \ x) ∪ (z \ y ) (De Morgan 2)

• x ∪ ∅ = x (Leere Menge 1)

• x ∩ ∅ = ∅ (Leere Menge 2)

• x ∩ (z \ x) = ∅ (Leere Menge 3)

69 / 95

Kardinalität

• Die Anzahl der Elemente einer Menge x schreiben wir als | x |

oder auch als card(x) (B Schreibweise).

• card ({1, 2, 3}) = 3

• card (∅) = 0

• Achtung, die Kardinalität kann auch unendlich sein: je nach

Formalismus, ist folgender Ausdruck entweder unendlich oder

nicht wohl definiert: | {x | x > 0} |

70 / 95

SEND+MORE=MONEY

• klassisches Puzzle wo acht unterschiedliche Ziffern gefunden

werden sollen.

• Wir können dies nun in Logik, Mengentheorie und Arithmetik

modellieren und lösen.

+

=

71 / 95

M

S

M

O

E

O

N

N

R

E

D

E

Y

SEND+MORE=MONEY - Formal

Logische, formale Spezifikation des Puzzles:

• Wir haben acht Ziffern: {S, E , N, D, M, O, R, Y } ⊆ 0..9

• die alle unterschiedlich sind:

card ({S, E , N, D, M, O, R, Y }) = 8

• und wobei zwei Ziffern ungleich 0 sind: S > 0 ∧ M > 0

• und wo die Summe von SEND+MORE MONEY ergibt:

S ∗1000+E ∗100+N ∗10+D +M ∗1000+O ∗100+R ∗10+E =

M ∗ 10000 + O ∗ 1000 + N ∗ 100 + E ∗ 10 + Y

• Lösung:

S = 9∧E = 5∧N = 6∧D = 7∧M = 1∧O = 0∧R = 8∧Y = 2

72 / 95

SEND+MORE=MONEY - Lösung

• von ProB gefundene (einzige) Lösung:

+

=

73 / 95

1

9

1

0

5

0

6

6

8

5

7

5

2

Mengen von Mengen

• Mengen können selber auch Mengen beinhalten

• Dies sind alles unterschiedliche Mengen:

• {{2}, {3, 4}},

• {{2, 3}, {4}} ,

• {{2, 3}, {3, 4}},

• {{2, 3, 4}},

• {2, 3, 4}

• Wir haben zum Beispiel:

• card ({{2, 3, 4}}) = 1

• card ({{2}, {3, 4}}) = 2

• card ({2, 3, 4}) = 3

• {2} ∈ {{2}, {3, 4}}

• {2} 6∈ {{2, 3}, {4}}

74 / 95

Mengen von Mengen: leere Menge

• ∅ 6= {∅}

• card (∅) = 0

• card ({∅}) = 1

• ∅ ∈ {∅}

• ∅ 6∈ ∅

• {∅} =

6 ∅

75 / 95

Potenzmenge

• Die Menge aller Untermengen einer Menge A schreiben wir als

P(A) oder auch als 2A .

• P({1, 2}) = {∅, {1}, {1, 2}, {2}}

• P(∅) = {∅}

• P({1, 2, 3}) =

•

•

•

•

{∅, {1}, {1, 2}, {1, 3}, {2}, {1, 2, 3}, {2, 3}, {3}}

P(P({1})) = {∅, {∅}, {∅, {1}}, {{1}}}

card (P({1, 2, 3})) = 8

card (P(1..10)) = 1024

card (P(1..100)) = 1267650600228229401496703205376

• card (P(P(1..7))) = 340282366920938463463374607431768211456

• card(P(P(P(1..3)))) =

11579208923731619542357098500868790785326998466564056403945758400791312963

76 / 95

Relationen

• Was ist eine Relation?

• Wie kann man Relationen in Mengentheorie und Logik

abbilden?

10

8

6

h

h

h

5

4

3

h

2

h

1

77 / 95

7

5

4

d

d

d

FALSE

2

d

1

d

6

3

d

TRUE

d

Unäre Relationen

• Eine unäre Relation über x ist einfach eine Untermenge von x:

die Menge an Werten für die die Relation wahr ist.

• Relation “Ziffer” über die ganzen Zahlen ist 0..9 ⊆ Z.

• Relation “Gt0” über die ganzen Zahlen ist

{x|x ∈ Z ∧ x > 0} ⊆ Z.

• Relation “Gerade” über die ganzen Zahlen ist {x|x ∈ Z ∧ x

mod 2 = 0} ⊆ Z.

Binäre Relationen?

78 / 95

Kartesisches Produkt und Paare

• Das kartesische Produkt x × y zweier Mengen x und y ist

definiert als {(a, b) | a ∈ x ∧ b ∈ y }.

• (a, b) steht hier für ein geordnetes Paar, d.h.

(1 7→ 2) 6= (2 7→ 1). Wir schreiben manchmal auch a 7→ b

anstatt (a, b).

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

79 / 95

(1..2) × (4..5) = {(1 7→ 4), (1 7→ 5), (2 7→ 4), (2 7→ 5)}

(1..2) × {4} = {(1 7→ 4), (2 7→ 4)}

(1..2) × ∅ = ∅

(1..2) × BOOL = {(1 7→ FALSE ), (1 7→ TRUE ), (2 7→

FALSE ), (2 7→ TRUE )}

(1..3) × (1..3) = {(1 7→ 1), (1 7→ 2), (1 7→ 3), (2 7→ 1), (2 7→

2), (2 7→ 3), (3 7→ 1), (3 7→ 2), (3 7→ 3)}

card ((1..10) × (1..10)) = 100

{1} × {2} =

6 {2} × {1} (Nichtkommutativität)

A × B = ∅ ≡ (A = ∅ ∨ B = ∅).

Binäre Relationen

• Eine binäre Relation über x und y ist eine Untermenge des

kartesischen Produkts x × y zweier Mengen. Die Mengen x

und y können identisch sein.

• Relation “kleiner” über die Ziffern 0..9:

{x, y |x ∈ 0..9 ∧ y ∈ 0..9 ∧ x < y } = {(0 7→ 1), (0 7→ 2), (0 7→

3), (0 7→ 4), (0 7→ 5), (0 7→ 6), (0 7→ 7), (0 7→ 8), (0 7→

9), (1 7→ 2), (1 7→ 3), (1 7→ 4), (1 7→ 5), (1 7→ 6), (1 7→

7), (1 7→ 8), (1 7→ 9), (2 7→ 3), (2 7→ 4), (2 7→ 5), (2 7→

6), (2 7→ 7), (2 7→ 8), (2 7→ 9), (3 7→ 4), (3 7→ 5), (3 7→

6), (3 7→ 7), (3 7→ 8), (3 7→ 9), (4 7→ 5), (4 7→ 6), (4 7→

7), (4 7→ 8), (4 7→ 9), (5 7→ 6), (5 7→ 7), (5 7→ 8), (5 7→

9), (6 7→ 7), (6 7→ 8), (6 7→ 9), (7 7→ 8), (7 7→ 9), (8 7→ 9)}.

Relationen kann man als explizite Darstellung von Prädikaten

ansehen.

80 / 95

Binäre Relationen - zwei Beispiele

• Relation “halb” über die ganzen Zahlen 1..10 ist

{x, y |x ∈ 1..10 ∧ y = x/2 ∧ x mod 2 = 0} = {(2 7→ 1), (4 7→

2), (6 7→ 3), (8 7→ 4), (10 7→ 5)}. Untermenge von Z × Z.

• Relation “durch drei teilbar” über die ganzen Zahlen 1..7 und

BOOL ist {(1 7→ FALSE ), (2 7→ FALSE ), (3 7→ TRUE ), (4 7→

FALSE ), (5 7→ FALSE ), (6 7→ TRUE ), (7 7→ FALSE )}.

Untermenge von Z × BOOL.

10

8

6

h

h

h

5

4

3

h

2

h

1

81 / 95

7

5

4

d

d

d

FALSE

2

d

1

d

6

3

d

TRUE

d

Definitions- und Wertebereich

• let h = {x, y |x ∈ 1..10 ∧ y = x/2 ∧ x mod 2 = 0}

{(2 7→

1), (4 7→ 2), (6 7→ 3), (8 7→ 4), (10 7→ 5)}

• let div = {x, y |x ∈ 1..7 ∧ y = bool (x mod 3 = 0)}

• Definitionsbereich (Domain): dom(r ) = {a | ∃b.((a, b) ∈ r )}

dom(h) = {2, 4, 6, 8, 10}

dom(div ) = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7}

• Wertebereich (Range): ran(r ) = {b | ∃a.((a, b) ∈ r )}

ran(h) = {1, 2, 3, 4, 5}.

10

8

6

h

h

h

5

4

3

h

2

h

82 / 95

1

7

5

4

d

d

d

FALSE

2

d

1

d

6

3

d

TRUE

d

Relationales Abbild und Umkehrrelation

• Abbild: r [A] = {b | ∃a.((a, b) ∈ r ∧ a ∈ A)}

h[{8, 9, 10}] = {4, 5}

div [{3, 6}] = {TRUE }.

• Umkehrrelation: r −1 = {(b, a) | (a, b) ∈ r }

h−1 = {(1 7→ 2), (2 7→ 4), (3 7→ 6), (4 7→ 8), (5 7→ 10)}

(div −1 )[{TRUE }] = {3, 6}.

10

8

6

h

h

h

5

4

3

h

2

h

1

83 / 95

7

5

4

d

d

d

FALSE

2

d

1

d

6

3

d

TRUE

d

Binäre Relationen - Verknüpfung

• wir können Relationen r1 und r2 mit dem Operator “;”

verknüpfen: (r1 ; r2 ) = {(a, c) | ∃b.((a, b) ∈ r1 ∧ (b, c) ∈ r2 )}.

• ({(1 7→ 2), (2 7→ 3)}; {(2 7→ 4), (2 7→ 8)}) = {(1 7→ 4), (1 7→

8)}.

Man kann eine Relation auch mit sich selber verknüpfen wenn

Werte- und Definitionsbereich kompatibel sind. Beispiel h=

{(2 7→ 1), (4 7→ 2), (6 7→ 3), (8 7→ 4), (10 7→ 5)} und h2 = (h; h):

10

8

6

h

h

h

5

4

3

h

2

8

4

h2

h2

2

1

h

1

84 / 95

Transitive Hülle

• r1 = r

• r k = (r k−1 ; r ) = (r ; r k−1 )

• r+ =

S

i>0 r

i

Beispiel h= {(2 7→ 1), (4 7→ 2), (6 7→ 3), (8 7→ 4), (10 7→ 5)} und

h2 = (h; h), h3 = (h2 ; h):

10

8

10

6

h

h

h

5

4

3

hth

5

h

1

85 / 95

6

hth

3

hth

hth

4

hth

h

2

8

8

4

h2

h2

2

1

8

hth

hth

2

h3

hth

1

1

Transitive Hülle: Beispiel

Abgeänderte strikte Untermengenrelation ⊂ für P(1..3):

{x, y |y ∈ P(1..3) ∧ x ⊂ y ∧ card (x) = card (y ) − 1} = {(∅ 7→

{1}), (∅ 7→ {2}), (∅ 7→ {3}), ({1} 7→ {1, 2}), ({1} 7→

{1, 3}), ({1, 2} 7→ {1, 2, 3}), ({1, 3} 7→ {1, 2, 3}), ({2} 7→

{1, 2}), ({2} 7→ {2, 3}), ({2, 3} 7→ {1, 2, 3}), ({3} 7→

{1, 3}), ({3} 7→ {2, 3})}.

{}

{}

sub1 sub1

sub1

sub

{3}

{1}

{2}

sub1

sub1

sub1

sub

sub

{2,3}

sub1 sub1

{1,2,3}

86 / 95

{3}

sub

{1}

sub

sub1 sub1 sub1

sub

{1,3}

sub

{2}

{1,2}

sub1

sub

sub

{2,3}

sub

sub

sub

sub

sub sub

{1,2}

sub

{1,2,3}

{1,3}

sub

sub

sub

Transitive und Reflexive Hülle

Gegeben eine Relation r von A nach A

• r 0 = {(a, a) | a ∈ A}

• r k = (r k−1 ; r ) = (r ; r k−1 )

S

• r ∗ = i≥0 r i

Zum Beispiel für A= {1, 2, 3} und let r = {(1 7→ 2), (2 7→ 3)}

haben wir r ∗ = closure(r ) = {(1 7→ 1), (1 7→ 2), (1 7→ 3), (2 7→

2), (2 7→ 3), (3 7→ 3)}.

1

1

r

2

rs

rs

2

r

3

87 / 95

rs

rs

rs

3

rs

Funktionen

• Was unterscheidet Funktionen von Relationen?

• Wie kann man Funktionen in Mengentheorie und Logik

darstellen?

{}

sub1 sub1

{3}

sub1

sub1

{1,3}

{1}

sub1

{2}

sub1 sub1 sub1

{2,3}

sub1 sub1

{1,2,3}

88 / 95

sub1

{1,2}

sub1

Funktionen

Eine Funktion F von A nach B ist

• eine Relation von A nach B (also eine Untermenge von

A × B), so dass

• ∀a.(a ∈ A ⇒ ∃b.((a, b) ∈ F ))

• ∀(a, b, c).(((a, b) ∈ F ∧ (a, c) ∈ F ) ⇒ b = c)

Beispiel: let F = {x, y |x ∈ P(1..2) ∧ y = card (x)}

{(∅ 7→

0), ({1} 7→ 1), ({1, 2} 7→ 2), ({2} 7→ 1)}

• wir schreiben F ∈ P(1..2) → N

• bei Funktionen kann man anstatt (a, b) ∈ F auch F (a) = b

schreiben, F ({1, 2}) = 2

{2}

{1}

F

F

1

89 / 95

{1,2}

{}

F

F

2

0

Folgen

• Es gibt verschiedene Schreibweisen für Folgen.

Zum Beispiel [1, 2] ist eine Folge bestehend aus der Zahl 1

gefolgt von der Zahl 2

• Was unterscheidet Folgen von Mengen?

• Wie kann man Folgen in Mengentheorie und Logik darstellen?

90 / 95

Folgen vs Mengen

• Die Reihenfolge der Elemente ist wichtig:

[1, 2] 6= [2, 1], während

{1, 2} = {2, 1}

• Elemente können mehrfach auftauchen:

[1, 1] 6= [1], während

{1, 1} = {1}

• Wie kann man Folgen in Mengentheorie und Logik darstellen?

91 / 95

Folgen mathematisch gesehen

Eine Folgen G von A Elementen der Länge n ist

• eine Funktion von 1..n nach A

let G = [22, 22, 33]

{(1 7→ 22), (2 7→ 22), (3 7→ 33)}

• wir schreiben G ∈ seq(N) oder aber auch G ∈ A∗ (mehr dazu

später)

• das n-te Element einer Folge G ist einfach G (n), zum Beispiel

G (2) = 22

• die Länge einer Folge ist einfach die Kardinalität der

unterliegenden Relation

3

G

33

92 / 95

2

1

G

22

G

Zusammenfassung Mengentheorie

• Mengen, Notationen (per Prädikat)

• Potenzmenge, Menge von Mengen, φ 6= {φ}

• kartesisches Produkt, Relationen als Menge von Paaren/Tupeln

• Definitionsbereich, Wertebereich, Abbild, Umkehrrelation

• Transitive Hülle

• Funktionen

• Folgen als Funktion von Z nach Wertebereich

93 / 95

Lernziele

• logische Formeln verstehen und schreiben können

• logische Beweise verstehen: Wahrheitstabelle, Widerspruch,

Deduktiver Beweis, Äquivalenzbeweis

• Mengenausdrücke nach Logik übersetzen können

• Problemstellung nach Logik und Mengentheorie übersetzen

können

94 / 95

Nach dem Sinn das Wort, und dann vom Wort zum Sinn

• Geschrieben steht: “Im Anfang war das Wort!”

• Hier stock ich schon! Wer hilft mir weiter fort?

• Ich kann das Wort so hoch unmöglich schätzen,

• Ich muß es anders übersetzen,

• Wenn ich vom Geiste recht erleuchtet bin.

• Geschrieben steht: Im Anfang war der Sinn.

Quelle: Faust, Studierzimmer. Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

95 / 95