`Shakespeare` als pdf file

Werbung

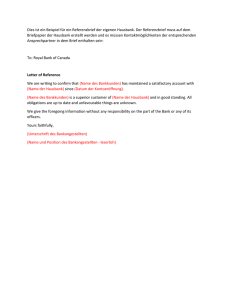

Nachhilfe Englisch Übersicht Unterrichtsmaterial Englisch Unterrichtsmaterial Fach Mathematik Klasse: 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Englisch . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . Deutsch Shakespeare Französisch Shakespeare and the Elizabethan World 1.1 The Elizabethan Period Elizabeth I was 25 years old when she became Queen of England in 1558. For 45 years she was governing the kingdom until her death in 1603. England was a nation with tremendous political power and unparalleled cultural achievement at the time. Since the English renaissance is to a large extend directly attributable to Elizabeth's personal character and influence, as well as to the unprecedented length of her reign, the last half of the Sixteenth Century in England is referred to as the Elizabethan Period. The fact that Elizabeth became Queen indicates some predestination towards greatness and defiance. The daughter of Henry VIII and his second wife, Anne Boleyn, who was later executed, Elizabeth was third in line of succession, following her younger half-brother Edward, son of Henry VIII and Jane Seymour, and her older half-sister Mary, daughter of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. Under normal circumstances, it would have been very unlikely that she mounted the throne. However, events did not follow their predicted course. The nine-year old Edward became King Edward VI on the death of Henry VIII in 1547. Yet, he had little opportunity to establish himself as a monarch, dying at the age of 15. He was succeeded by Mary I (1553 - 1558) whose efforts to return England to Catholicism brought about a regime of terror. When Mary died suddenly in 1558, Elizabeth became Queen of England. In both intellect and temperament, Elizabeth was well-suited for the role of a monarch. She was exceptionally well-educated, having been tutored at her father's court by Roger Ascham, one of the most outstanding scholars and thinkers of the time. Her intellectual interests were broad, ranging from history and science to art, literature, and philosophy, and she was a remarkably clever political strategist. She returned the country to internal political and religious stability in the wake of "Bloody Mary's" reign, and she directed England's course as it became powerful among other European nations. Both Spain and France felt the effects of England's growing strength under Elizabeth's rule. Furthermore, she noticed that great political advantages could be gained from her status as an unmarried monarch, and throughout her reign various political alliances via marriage were implied but never finalized. Elizabeth was an enormously popular monarch and one of Western civilization's first true cult figures. The following of "The Virgin Queen," or "Gloriana," as she was called, was extensive; according to many historians, every public appearance became an occasion for grand spectacle and huge crowds. The Queen's taste in fashion set the standard for the aristocracy and well-off society; her love of music, drama, and poetry led to an atmosphere in which many of England's greatest writers found encouragement and financial patronage. Under Elizabeth's leadership, England experienced the true cultural renaissance of thought, art and vision, which had begun in Italy a Century earlier. Elizabeth's court was a magnet that attracted the most talented individuals of the Century, and, at the Queen's direction, Oxford and Cambridge Universities were reorganized as centers for learning and scholarly endeavor. England during the reign of Elizabeth I was a country of huge ambition, achievement, promise, and gusto. Sir Francis Drake’s circumnavigation of the world from 1577 until 1580 added to the nation's prestige and competitiveness in navigation and exploration. However, the climax of England's power at sea was the triumphant defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588. It secured the nation's position as a world power. With the chartering of the East India Company in 1599, England entered the arena of world trade and colonization, which it dominated for the next three Centuries. The prosperity, confidence, and optimism, which characterized Elizabeth's court and reign carried over into many aspects of life. Literature created during the Elizabethan Period can be divided into two categories: poetry and drama. Influenced by the Italian sonnet, which had been introduced into the English language by Sir Thomas Wyatt (1503-1542) during the reign of Henry VIII, English poets began to construct their own variations on this highly structured poetic form. Others, like Edmund Spenser (1552-1599) in his extraordinarily ambitious poems of homage to Elizabeth, The Faerie Queen, adapted sonnet patterns into forms of their own invention. Even William Shakespeare varied the rhyme scheme and patterns of the sonnet form to suit his own purposes in an elaborate sequence or "cycle" consisting of more than one hundred sonnets. The other great literary achievement of the Elizabethan Period was the drama, a form which was enrooted in centuries of popular folk entertainment and which had been adapted into the religious plays of the Middle Ages. As the Sixteenth Century progressed, playwrights increasingly moved their plots from the simplistically religious to the secular, weaving into their dramas such diverse elements as legend and myth, classical dramatic forms, intense exploration of character, and familiar conventions freely adapted from works of their contemporaries. The dramatic form allowed playwrights to simultaneously develop plot, theme, complex characters, and poetic language which, at its best, as in the famous Shakespearean tragedies, pushed the English language to new heights of imaginative achievement. Other famous Elizabethan playwrights and authors were: Christopher Marlow - Playwright and Author Francis Beaumont - Playwright and Author John Fletcher - Playwright and Author Thomas Middleton - Playwright and Author Thomas Kyd - Playwright and Author 1564 - 1593 1584 - 1616 1579 - 1625 1580 - 1627 1558 - 1594 The Queen herself wrote poems and music. Everyone, regardless of social class, enjoyed the spectacle of the Elizabethan theatre. Playwrights found themselves writing for highly diverse audiences which reflected the ever-changing makeup and energy of society. It was not unusual for a crowd to take in a morning of public executions, bear-baiting, street carnivals, and fairs before settling down for an afternoon performance at one of the public theatres in London like „The Globe“ or “The Swan”. The Globe, built between 1597 – 1598 by carpenter Peter Smith and his workers, was the most magnificent theatre that London had ever seen. This theatre could hold several thousand people. The famous Globe Theatre did not only show plays. Not one inside picture of the old Globe Theatre is in existence; however, a picture of another amphitheatre, the Swan, has survived. Since the amphitheatres were similar in design, the picture of the Swan Theatre can be used guide to the structure of the old Globe. Picture of the Swan Theater There were three different types of venues for Elizabethan plays: “Inn-Yards”, “Playhouses” and “Open Air Amphitheatres”. The Inn-Yards were the original venues of plays and many were converted into playhouses. These Inn-Yards represented the early days of the Elizabethan commercial theatre. They had an audience capacity of up to 500 people. The amphitheatres were generally used during the summer months. Their structure was similar to a Coliseum or a small footbal stadium with a capacity of up to 3000 people. During the winter season the Acting Troupes moved to the indoor playhouses. The audience capacity in indoor playhouses was up to 500 people. These playhouses were open to anyone who would pay. Sometimes there were more selected audiences, than the price was higher, of course. The most successful playwrights of the day made sure that their dramas included "something for everybody". Jokes and physical side gags for the peasant "groundling" that stood at the foot of the stage, scenes of action and intrigue for the middle class spectator, or elevated language and characters to appeal to the more educated upper class citizen who sat in the galleries around the outdoor stage. The last years of Elizabeth's reign were not always politically smooth; in fact, by the 1590's there was at least one serious threat of rebellion, as well as a series of bitter Parliamentary conflicts. But Elizabeth was steadfast as a monarch and held things firmly in control until her death in 1603. It marked not only the end of the Tudor line, but of a glorious era in English history. Successor was her cousin, King James VI of Scotland, who united the two nations as King James I. 1.2 William Shakespeare William Shakespeare, probably the world's most performed and admired playwright, was born in April, 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon, about 100 miles Northwest of London. The actual date of birth is not recorded, which is common for Sixteenth Century births. According to the records of Stratford's Holy Trinity Church, he was baptized on April 26. Since it was customary to baptize infants within days after birth, it has become traditional to assign the birth day to April 23, which is also St. George's Day, the patron of England. Shakespeare died 52 years later on April 23, 1616. His parents John and Mary Shakespeare lived in Henley Street, Stratford-upon-Avon. John was a maker, worker and seller of leather goods, like purses, belts and gloves and a dealer in agricultural commodities. He was a solid, middle class citizen at the time of William's birth, and a man on the rise. He served in Stratford government successively as a member of the council (1557), constable (1558), chamberlain (1561), alderman (1565) and finally high bailiff (1568) - the equivalent to town mayor. Mary and her husband had eight children altogether. William was the third child and the first son. On November 28, 1582 William married Anne Hathaway. She was eight years older than her new husband.The banns were asked only once in church, rather than the customary three times, because the bride was three months pregnant and there was reason for haste in concluding the marriage. In just 23 years, between 1590 and 1613 approximately, Shakespeare wrote 38 plays, 154 sonnets and 5 other poems. Around 1587 he moved from Stratford to London and established himself as an actor and playwright. Between 1594 and 1596 he wrote his lyrical masterpieces - Midsummer Night’s Dream, Romeo and Juliet, and The Merchant of Venice. Between 1600 and 1608 Shakespeare wrote his great tragedies and problem plays - Hamlet, Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth. In all probability in 1612, he retired from London life back to Stratford. On April 23, 1616 Shakespeare died in Stratford. Shakespeare's work has made a lasting impression on later theatre and literature. He expanded the dramatic potential of characterization, plot, language and genre in particular. Until Romeo and Juliet, for example, romance had not been viewed as a worthy topic for a tragedy. Soliloquies had been used mainly to convey information about characters or events; but Shakespeare used them to explore the mind of his characters. He wrote at a time when English grammar and spelling were not fixed, and his use of language shaped modern English sustainably. The language used today is in many ways th different to the 16 century Elizabethan Period. It is therefore not surprising that you have no experience or understanding of some of the words used in his various works. The texts conveyed vivid impressions. Shakespeare’s body of work featured many famous and well loved characters, too. Even today, the words of Shakespeare can be found everywhere! He influenced many novelists including William Faulkner and Charles Dickens. Shakespearean quotations can be heard on the radio and on television on a daily basis and are part of everyday life. The advertising media love to make use of his sayings. Famous authors even refer to Shakespearean quotations as titles for their books, for instance Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World: The Tempest, Act V, scene 4: “Oh brave new world that has such people in it”. One of the most famous quote of Shakespeare’s work in total is "To be, or not to be: that is the question" (Hamlet, Act III, scene 1). 2. Shakespeare’s imagery and language William Shakespeare employed figures of speech, for example imagery or metaphors, to express something of importance. By means of these figures he wants to o o o say more about points made in dialogue and action, reinforce and enhance the audience's ideas of the characters, magnify or draw attention to themes/issues in the text. For reaching his aim, he used a lot of means you already know. Therefore, the following is only a repetition. Nevertheless, read it carefully to understand the importance of Shakespeare’s language for your own text analysis. a. Similes: comparisons using 'as' or 'like': "The moon is like a balloon" b. Personification: giving human feelings to animals or inanimate objects. c. Metaphors: stronger comparisons, saying something is something else: "The moon is a balloon." d. Extended metaphors: a metaphor that is used extensively throughout a passage. Read Portia's speech from The Merchant of Venice. The quality of mercy is not strain'd; It droppeth as the gentle rain from heaven Upon the place beneath. It is twice blest: It blesseth him that gives and him that takes. 'Tis mightiest in the mightiest; it becomes The throned monarch better than his crown; His sceptre shows the force of temporal power, The attribute to awe and majesty, Wherein doth sit the dread and fear of kings; But mercy is above this sceptred sway, It is enthroned in the hearts of kings, It is an attribute to God himself; And earthly power doth then show likest God's. Task 1: What are the 'qualities of mercy' according to this extended metaphor? e. Oxymoron: A word or phrase(s) that are opposed to each other but paired for effect. As soon as Juliet hears that Tybalt, her cousin, has been killed by Romeo, her grief and outrage is tempered by her disbelief that Romeo could carry out such a deed: "Fiend angelical, dove-feathered raven, wolvish-ravening lamb ... A damned saint, an honourable villain!" (Romeo and Juliet, Act 3, scene 2, lines 75-79) f. Motifs: characters, themes or images which recur throughout a text. In Macbeth there are several motifs. One is 'fair and foul' and another is 'sleep'. To the Weird Sisters, who characterize evil, what is 'ugly' is 'beautiful', and what is 'beautiful' is 'ugly': "Fair is foul and foul is fair." (Reversal of values) Macbeth and Lady Macbeth reign in restless ecstacy after murdering King Duncan. Macbeth soon says to illustrate the sleep motif: "Me thought I heard a voice cry, 'Sleep no more!' Macbeth does murder sleep - the innocent sleep, Sleep that knits up the ravelled sleave of care, The death of each day's life, sore labour's bath, Balm of hurt minds, great nature's second course Chief nourisher in life's feast." (Macbeth, Act 2, scene 2, lines 34-39) 3. Shakespeare’s style of writing In general, Shakespeare uses three styles of writing in his plays. I. Poetic verse (rhymed) This is often used to signal the end of scenes like a curtain call or for heightened dramatic effect. II. Blank verse (unrhymed) A blank verse is intended to represent rhythms of speech. It is usually used by noble charcters who are given elevated speech to show their feelings and mood. III. Prose Ordinary language used by characters of all ranks. Uneducated characters tend to use it. It can also be used for comic exchanges between charcters, for plot development and for speech which lacks dramatic intensity. 4. Example: Macbeth 4.1 Zusammenfassung Since Shakespeare’s dramas are not always easy to understand for non-native speakers, the following summary is in German. "So fein und faul war nie ein andrer Tag" – das ist das seltsame Statement eines Siegers, General Macbeth, der auf das Schlachtfeld blickt. Hoch- und Landesverrat sind niedergeschlagen, die norwegischen Eindringlinge vertrieben, Schottland kann einem neuen Frieden entgegensehen. Aber auf dem Weg zu ihrem König Duncan begegnen den Feldherren Macbeth und Banquo drei Hexen - und ihre Prophezeiungen stellen Macbeths Welt auf den Kopf. König von Schottland soll Macbeth, Banquo der Stammvater von vielen Königen werden, so orakeln die Hexen. Banquo misst dem ganzen wenig Bedeutung zu, Macbeth dagegen ist fasziniert: „Than of Glamis“ glaubt er bereits zu sein, als „Than of Cawdor“ huldigen ihm im nächsten Augenblick die Abgesandten des Königs. Da kann doch die Erfüllung der dritten Verheißung nicht mehr weit sein, doch diese führt nur über den Königsmord. Anders als der, trotz des großen Reizes, eher zögerlich reflektierende Macbeth, ist seine Frau, Lady Macbeth, zu der Mordtat bereit. Sie stachelt ihren Gatten auf und ermutigt ihn zum letzten Schritt, wobei das Schicksal auch noch die Gelegenheit dazu schafft: König Duncan verbringt eine Nacht in Macbeth' Schloss. Macbeth tötet den wehrlos Schlafenden und mithilfe seiner Frau wird der Verdacht auf die Wächter gelenkt. Von Grauen gepackt fliehen Duncans Söhne ins Ausland. Macbeth wird König von Schottland. Dennoch hat er nur wenig Freude an seinem Leben und seinem Thron. Es ist ihm auch nicht gelungen, seine Position unangreifbar zu machen. Es gibt keinen Augenblick, in dem Macbeth sein Königtum oder seinen neue Machtfülle genießen kann und sein Hofleben auskostet. Er ist voller Sorgen und Angst und fühlt sich von allen verfolgt. Bald beschließt er, den Mitwisser der drei Prophezeiungen, Banquo, töten zu lassen. Ihm war durch die Hexen vorausgesagt worden, Stammvater vieler Könige zu werden. Dem kinderlosen Macbeth ist genau das ein Dorn im Auge und er will nicht nur Banquo, sondern auch dessen Sohn Fleance töten lassen. Banquo fällt den Mördern zum Opfer, sein Sohn kann entkommen. Banquos Geist erscheint daraufhin mahnend auf einem Gastmahl vor Macbeths Augen. Lady Macbeth versucht die Getreuen des Königs zu beschwichtigen, die sich wegen des eigentümlichen Verhaltens ihres Königs sehr beunruhigt fühlen. Macbeth, völlig verunsichert, geht erneut zu den Hexen, um sie nach seiner Zukunft zu befragen. Sie versichern ihm, dass er keinen Mann fürchten muss, der „vom Weibe geboren“ sei und Macbeth niemals Gefahr drohe, bis dass der Wald zum Berg von Dunsinane marschiert. Macbeth fühlt sich zunehmend sicherer. Dafür schafft seine Frau nun nicht mehr, das Geschehene zu verarbeiten. Lady Macbeth versucht sich immer wieder schlafwandelnd das unsichtbare Blut von den Händen zu waschen - das Blut des ermordeten Königs Duncan. Sie kann diesem psychischen Druck nicht mehr standhalten und stirbt schließlich. Gegen Macbeth haben sich unter der Führung von Duncans Sohn Malcolm und Macduff, des „Thans of Fife“, Engländer und Schotten verbündet. Ihre Truppen nähern sich getarnt mit den Zweigen des Waldes. Es sieht so aus, als ob sich der Wald auf das Schloss zu bewege. Im Zweikampf gegen Macduff, der zu seiner Geburt „aus dem Mutterleib geschnitten“ wurde und so die Prophezeiungen der Hexen erfüllt, fällt schließlich auch Macbeth und Malcolm wird König von Schottland. 4.2 Zusätzliche Informationen Jakob I., der Nachfolger Königin Elizabeths I., hielt 1605 seinen feierlichen Einzug in Oxford. Dort traten ihm am Nordtor der Stadt drei Studenten entgegen, die als Hexen verkleidet waren, und begrüßten ihn, den Nachkommen Banquos, mit einem lateinischen Gedicht, das ein Londoner Professor unter Verwendung einer alten Sage für diese Gelegenheit geschrieben hatte. Shakespeare fand in einer Chronik die Beschreibung der schottischen Vorzeit, in der Zauberer und Hexen eine enorm große Rolle spielten. Die Erzählung von Macbeth, dem Königsmörder, fand sich im Großen und Ganzen bereits in der Chronik. Der historische König Macbeth, der das schottische Reich von 1040 -1057 regierte, war allerdings ein ganz anderer Charakter als Shakespeares Macbeth. Er lebte in einer Zeit, als Angelsachsen, Norweger, Pikten und Skoten eine eigenwillige Mischung in Schottland bildeten. Die heidnischen Sitten, die durch die norwegischen Eroberer ins Land gekommen waren, hatten sich mit dem etwas barbarischen Christentum der keltischen Einwohner zu einer Kultur verbunden, in der Faustrecht und Aberglaube Schottland nicht zur Ruhe kommen ließen. In diesen Rahmen passte es, dass am 14. August 1040 König Duncan I., ein schwacher, junger Herrscher, nach einem unglücklichen Kampfe mit seinem Vetter Thorfin, dem Jarl (= Führer) der norwegischen Orkneyer, welcher ihn flüchten ließ, von seinem eigenen Feldherrn Macbeth ermordet wurde. Shakespeare verarbeitete diesen Stoff zu einer Tragödie. Die fein herausgearbeiteten Seelenbilder, Banquos Geist, das Nachtwandeln der Lady Macbeth oder Macbeths letzten Widerstand gehen auf sein künstlerisches Schaffen zurück. 4.3 Characters The two main characters of the play are Macbeth and his wife Lady Macbeth. The following information is in German in order to understand these complex characters. Ein wesentlicher Zug von Macbeths Charakter ist seine Phantasie. Im Feld ein tapferer Soldat, dagegen wie im Rausch, wenn er allein ist und die Bilder seiner Vorstellungskraft ihn umgeben. In ihm ist der Wunsch nach dem Bösen vorhanden, der Wille zum Guten eher schwach ausgeprägt, er "möchte falsch nicht spielen und unrecht doch gewinnen". Er möchte überhaupt immer alles, aber wie – das ist die Frage. Gegen seine Frau ist er absolut zögerlich. Trotzdem verkörpert er eben nicht grundsätzlich nur das Böse. Sein Charakter ist durchaus gespalten, daher kann er auch als tragischer Held bezeichnet werden. Sein Gegenpart ist Lady Macbeth. Sie hat den starken Willen, der sie auf das einmal gesteckte Ziel festen Schrittes losgehen lässt, ohne ängstlich die Folgen zu bedenken. Sie fühlt sich nicht gebunden durch Begriffe von Ehre und Moral, auch vor einem Verbrechen schreckt sie nicht zurück, wenn sie glaubt, dass der Preis es rechtfertigt. Lady Macbeth gibt ihrem Ehemann Kraft, bis er den Königsmord begeht. Sie geht auch, ohne zu zögern, in die Kammer, in der der Tote liegt, um mit seinem Blut die schlafenden Diener zu beschmieren. Und dennoch ist hier die „klassische“ Konstellation Frau – Mann geschildert: Als der Rausch vorüber ist, als die Verbrechen ruchbar werden und die Großen des Landes anfangen, sich von dem Paar zurückzuziehen, ist sie es, die nervlich zusammenbricht. Macbeth wird gleichzeitig wieder der tapfere Krieger, vor allem, wenn er seinem Feind gegenübersteht. Neue Prophezeiungen der Hexen haben ihn gestärkt, aber im Wesentlichen ist es nur ein Hervorbrechen der alten Kraft, die er als Mörder verloren hatte. Das Bild der beiden Menschen ist trotz allem nicht nur blutrünstig, sondern durch die innige, treue Liebe, mit der sie einander begegnen, auch anrührend. Es hat zweifellos etwas Rührendes, wie Macbeth immer mehr um seine Frau besorgt ist. Man merkt, dass das Verbrechen diese beiden Menschen noch fester zusammen geschmiedet hat. Below you find a list of the main characters of the play: Duncan Duncan, the King of Scotland, is Macbeth's first victim on his way to become king. As it is evident here, Shakespeare was a firm believer in the divine right of kings. Murdering the king was always the most serious of crimes, and murdering a benevolent monarch was wicked beyond comprehension. Duncan was a delightful and beloved king and with his 'silver skin' and 'golden blood' Shakespeare's Duncan symbolized the perfect ruler. Macbeth The horrific and detestable acts commited by Macbeth mirror the crimes of Shakespeare's great miscreants, like Aaron the Moor, Iago, or Richard III, all ready to slaughter women and children, usurp divinely appointed kings, and butcher their closest friends to satisfy their ambitious aims. Yet, despite his very bad deeds, Macbeth is not among the list of Shakespeare's most base evils. What sets Macbeth apart is his preferance for self-reflection. Although ultimately he cannot resist his dark desires, his struggle to regain his goodness is constant, and the part of his character that is capable of deep love and compassion, although ever fading, is always present. Thus, rather than evil or a criminal in general, Macbeth is considered to be one of Shakespeare's tragic heroes. He does not epitomize the Aristotelian tragic hero, like Hamlet, but he is a tragic hero nonetheless, because we, the audience, can relate to him. The struggle between good and bad is one of his characteristics and he slowly shatters because of his crime instead of finding fulfilment as a king. Lady Macbeth Lady Macbeth is Shakespeare's most evil feminine creation. Her satanic prayer to the forces of darkness in Act 1 is creepy to modern readers. The analysis of Lady Macbeth focuses on her as catalyst for Macbeth's first murder, that of Duncan, and the linear progression of her mental state, becoming worse and worse, culminating in her 'sleepwalking scene.' However, the most interesting facet of Lady Macbeth's character is hardly ever explored. She herself intends to commit the murder of Duncan, while her husband plays the smiling host. This precious detail gives Lady Macbeth's invocation new weight and her character new depth. The aspect of Lady Macbeth's “prayer” is that she intends to murder Duncan herself. She speaks of 'my knife' and of 'my fell purpose.' And the same resolve is implied in everything she says to Macbeth after his entry. She bids him put "This night's great business into my dispatch", she tells him he doesn’t need to do anything, but look as the innocent and kindly host; she dismisses him with the words 'Leave all the rest to me'. In the end, the murder is performed by Macbeth himself, but she is the one who plays a major role in the murder. Banquo Shakespeare's Banquo is the antithesis of Macbeth, the brave, noble general. With his pure, moral character he is the contrast to Macbeth. Banquo has no extreme ambitions and thus can easily escape the trap of the witches' prophesies. Wise and steadfast, Banquo warns Macbeth that ”Oftentimes, to win us to our harm, The instruments of darkness tell us truths, Win us with honest trifles, to betray’s In deepest consequence.” (Act 1, Scene3, 132) Banquo ultimately becomes a victim of Macbeth, but his son, Fleance, escapes. Macduff Macduff, the Thane of Fife, arrives at Macbeth's castle the morning after Duncan has been murdered. Macduff pronounces the king’s dead, and is immediately suspicious of Macbeth. Macduff quickly sides with Malcolm, Duncan's son and rightful heir to the throne. As punishment for his betrayal, Macbeth plans to kill Macduff and his entire family. Macbeth's assassins do murder Lady Macduff and his son, but Macduff, who is in England at the time, lives to take revenge on Macbeth at the end of the play. It is him that kills Macbeth on the battlefield and carries his head to the new king, Malcolm. Malcolm Malcolm is the son of Duncan. He appears weak and uncertain of his own power when he and Donalbain flee Scotland after their father’s murder. However, with Macduff’s help and the support of England, Malcolm becomes a serious challenge to Macbeth. His restoration to the throne signals Scotland’s return to order after Macbeth’s reign of terror. Fleance Fleance is Banquo’s son, who survives Macbeth’s attempted murder. At the end of the play, Fleance’s whereabouts are unknown. He may come to rule Scotland, fulfilling the witches’ prophecy that Banquo’s sons will sit on the Scottish throne. The Three Witches Firstly, the three witches symbolise the supernatural. Three “black and midnight hags” use charms, spells, and prophecies. Their predictions prompt him to murder Duncan, to order the deaths of Banquo and his son, and to blindly believe in his own immortality. The play leaves the witches’ true identity unclear, aside from the fact that they are servants of Hecate, we know little about their place in the cosmos. In some ways they resemble the mythological fates, who impersonally weave the threads of human destiny. They clearly take a perverse delight in using their knowledge of the future to toy with and destroy human beings. The speeches of the witches’ rhyme which make them seem slightly ridiculous, more like caricatures of the supernatural. They speak in rhyming couplets (their most famous is probably “Double, double, toil and trouble, / Fire burn and cauldron bubble”), which separates them from the other characters, who mostly speak in blank verse. The witches’ words seem almost comical. Despite the absurdity of their “eye of newt and toe of frog” recipes, however, they are clearly the most dangerous characters in the play, being tremendously powerful. 4.4 Hints for Interpretation Macbeth is Shakespeare's shortest tragedy, and certainly, the most reworked of all of Shakespeare's plays. Be aware of the important motifs in the play, and make notes when you find them in the relevant passages. By making notes you will be well-prepared to discuss any theme in an exam or debate any point in an essay with specific references to the text. Reading a comprehensive edition like the “New Cambridge Shakespeare” ensures that you will understand the passage as a whole and not just the difficult or obsolete words. First of all, have a look at two lines of the play which you may already know and which are important for the drama’s story. o "what 's done is done", Macbeth Act 3, Scene 2. Macbeth has done his work to fulfill the prophecy. o "Fair is foul, and foul is fair", Macbeth Act 1, Scene 1. This phrase symbolizes the reversal of values, an aspect which is important throughout the whole play. Formal and content aspects: o Narrator - Not applicable (drama) o Point of view - Not applicable (drama) o Tense - Not applicable (drama) o Tone - Dark and ominous, suggestive of a world turned topsy-turvy by foul and unnatural crimes o Time - The Middle Ages (11 Century) o Place - Various locations mainly in Scotland, briefly also England o Protagonist - Macbeth th Themes o The corrupting nature of unchecked ambition, o the relationship between cruelty and masculinity, o the difference between kingship and tyranny. Major Conflicts o The struggle within Macbeth between his ambition and his sense of right and wrong, o the struggle between the murderous evil represented by Macbeth and Lady Macbeth and o the best interests of the nation, represented by Malcolm and Macduff. Rising Action o Macbeth and Banquo’s encounter with the witches initiates both conflicts, o Lady Macbeth’s speeches lead Macbeth into murdering Duncan. Climax o Macbeth’s murder of Duncan in Act II represents the point of no return, after which Macbeth is forced to continue butchering his subjects to avoid the consequences of his crime. Falling Action o Macbeth’s increasingly brutal murders (of Duncan’s servants, Banquo, Lady Macduff and her son), o Macbeth’s second meeting with the witches, o Macbeth’s final confrontation with Macduff and the opposing armies. Motifs o o o o o o The supernatural, hallucinations, insomnia, guilt, violence, prophecy. Symbols o Blood, o the dagger that Macbeth sees just before he kills Duncan in Act II, o the weather. Foreshadowing o In Act I the bloody battle foreshadows the bloody murders later on. o When Macbeth thinks he hears a voice while killing Duncan, it foreshadows the insomnia that plagues Macbeth and his wife. o Macduff’s suspicions of Macbeth after Duncan’s murder foreshadow his later opposition to Macbeth. o All of the witches’ prophecies foreshadow later events. 4.5 Themes and symbols The Corrupting Power of Unchecked Ambition The main theme of Macbeth - the destruction brought when ambition goes unchecked by moral constraints - finds its most powerful expression in the play’s two main characters. Macbeth is a brave Scottish general who is not naturally inclined to commit evil deeds, yet he deeply desires power and advancement. He kills Duncan against his better judgment and afterward stews in guilt and paranoia. Towards the end of the play he descends into a kind of frantic, boastful madness. Lady Macbeth, on the other hand, pursues her goals with greater determination, yet she is less capable of withstanding the consequenzes of her immoral acts. One of Shakespeare’s most forcefully drawn female characters; she encourages her husband mercilessly to kill Duncan and urges him to be strong in the murder’s aftermath. Eventually, she is driven to distraction by the effect of Macbeth’s repeated bloodshed on her conscience. In each case, ambition, encouraged of course, by the prophecies of the witches, is what drives the couple to ever more terrible acts. The problem, the play suggests, is that once one decides to use violence to further one’s quest for power, it is difficult to stop. There are always potential threats to the throne, Banquo, Fleance, Macduff, and it is always tempting to use violent means to dispose of them. The Relationship between Cruelty and Masculinity Characters in Macbeth frequently dwell on issues of gender. Lady Macbeth manipulates her husband by questioning his manhood, wishes that she herself could be “unsexed,” and does not contradict Macbeth when he says that a woman like her should give birth only to boys. In the same manner, Macbeth provokes the murderers he hires to kill Banquo by questioning their manhood. Such acts show that both Macbeth and Lady Macbeth equate masculinity with naked aggression, and whenever they converse about manhood, violence soon follows. This understanding of manhood allows the political order to descend into chaos. At the same time, however, the audience cannot help noticing that women are also sources of violence and evil. The witches’ prophecies spark Macbeth’s ambitions and then encourage his violent behavior; Lady Macbeth provides the brains and the will behind her husband’s plotting; and the only divine being is Hecate, the goddess of witchcraft. The aggression of the female characters is more striking because it goes against prevailing expectations of how women ought to behave. Lady Macbeth’s behavior certainly shows that women can be as ambitious and cruel as men. The play gives a less destructive definition of manhood. In the scene where Macduff learns of the murders of his wife and child, Malcolm consoles him by encouraging him to take the news in “manly” fashion, by seeking revenge upon Macbeth. Macduff shows the young heir apparent that he has a mistaken understanding of masculinity. To Malcolm’s suggestion, “Dispute it like a man,” Macduff replies, “I shall do so. But I must also feel it as a man” (Act 4, Scene 3). At the end of the play, Siward receives news of his son’s death rather complacently. Malcolm responds: “He’s worth more sorrow [than you have expressed] / And that I’ll spend for him” (Act 5, Scene 11). Malcolm’s comment shows that he has learned the lesson Macduff gave him on the sentient nature of true masculinity. It also suggests that, with Malcolm’s coronation, order will be restored to the Kingdom of Scotland. The Difference between Kingship and Tyranny Duncan is always referred to as the “king,” while Macbeth soon becomes known as the “tyrant.” The difference between the two types of rulers seems to be expressed in a conversation in Act 4, Scene 3, when Macduff meets Malcolm in England. In order to test Macduff’s loyalty to Scotland, Malcolm pretends that he would make an even worse king than Macbeth. He tells Macduff of his qualities; among them a thirst for personal power and a violent temperament, both of which seem to characterize Macbeth perfectly. Malcolm on the other hand says: “The king-becoming graces / [are] justice, verity, temp’rance, stableness, / Bounty, perseverance, mercy, [and] lowliness” (Act 4. Scene 3). The model king, then, offers the kingdom order and justice, but also comfort and affection. Under him, subjects are rewarded according to their merits, as when Duncan makes Macbeth Thane of Cawdor after Macbeth’s victory over the invaders. Most importantly, the king must be loyal to Scotland above his own interests. Macbeth, by contrast, brings only chaos to Scotland, which is symbolized by the bad weather and bizarre supernatural events. He offers no real justice, only murdering those he views as enemies. As the embodiment of tyranny, he must be overcome by Malcolm so that Scotland can have a true king once more. Hallucinations There are hallucinations throughout the play. They serve as reminders of Macbeth’s and Lady Macbeth’s guilt. When he is about to kill Duncan, Macbeth sees a dagger floating in the air. Covered with blood and pointing towards the king’s chamber, the dagger represents the bloody course on which Macbeth is about to embark. Later, he sees Banquo’s ghost sitting in a chair at a feast, pricking his conscience by mutely reminding him that he murdered his former friend. The seemingly hard-headed Lady Macbeth also eventually gives way to visions, as she sleepwalks and believes that her hands are stained with blood that cannot be washed away by any amount of water. In each case, it is ambiguous whether the vision is real or purely hallucinatory. Violence Macbeth is a violent play. Most of the murders take place offstage, but throughout the play the characters provide the audience with descriptions of the carnage, from the opening scene where the captain describes Macbeth and Banquo wading in blood on the battlefield, to the endless references to the bloodstained hands of Macbeth and his wife. The action is in between two bloody battles: in the first battle, Macbeth defeats the invaders; in the second, he is slain and decapitated by Macduff. Furthermore, the action itself is full of murders; Duncan, Duncan’s chamberlains, Banquo, Lady Macduff, and Macduff’s son are all killed as the story progresses. In the end, blood seems to be everywhere. Prophecy The witches’ prophecy that Macbeth will become first Thane of Cawdor and later king is the prophecy that sets Macbeth’s plot into motion. The three witches make a number of other prophecies: they predict that Banquo’s heirs will be kings, Macbeth should beware Macduff, Macbeth is safe till Birnam Wood comes to Dunsinane, and that no man born of a woman can harm Macbeth. Save for the prophecy about Banquo’s heirs, all of these predictions are fulfilled within the course of the play. Blood Blood is everywhere in Macbeth, beginning with the opening battle between the Scots and the Norwegian invaders. Once Macbeth and Lady Macbeth embark upon their murderous journey, blood comes to symbolize their guilt, and they begin to feel that their crimes have stained them in a way that cannot ever be washed clean. “Will all great Neptune’s ocean wash this blood / Clean from my hand?, ”Macbeth cries after he has killed Duncan, even as his wife scolds him and says that a little water will do the job (Act 2, Scene2). Later, though, she comes to share his horrified sense of being stained: “Out, damned spot; out, I say . who would have thought the old man to have had so much blood in him?” (Act 5, Scene 1) she asks as she wanders through the halls of their castle near the ending of the play. Blood symbolizes guilt. The Weather As in other Shakespearean tragedies, Macbeth’s murders are accompanied by a number of unnatural occurrences. From the thunder and lightning that accompany the witches’ appearances to the terrible storms that rage on the night of Duncan’s murder. These violations of the natural order reflect corruption of political order and morals. 4.6 Tasks 1. Discuss King Duncan and examine in how far he contributes to the play. 2. In constructing Macbeth, Shakespeare dramatically altered historical characters to enhance certain themes. Examine Shakespeare's sources and discuss why he made these radical changes. 3. Is Lady Macbeth more responsible than Macbeth for the murder of King Duncan? Is Lady Macbeth a more evil character than her husband? Why (or why not)? 4. The sleepwalking scene in Act V is one of the most memorable in the drama. Relate this scene to the overall play and examine what makes Lady Macbeth's revelation so provoking. 5. Choose two of the minor characters in Macbeth and examine how they contribute to the play's action. 6. The witches tell Banquo that he will be the father of future kings. How does Banquo's reaction reveal his true character? 7. Characterize the relationship between Macbeth and Lady Macbeth. If the main theme of Macbeth is ambition, whose ambition is the driving force of the play (Macbeth’s, Lady Macbeth’s, or both)? 5. Shakespeare’s sonnets and Elizabethan poetry There are no documented records of when the sonnets were written and there is even some doubt as to their true authorship. It is, however, certain that Shakespear had written some sonnets as in 1598 Francis Meres, in a "survey" of poetry and literature, made reference to the Bard and "his sugared sonnets among his private friends." The sonnets were intended as a form of private communication, some perhaps to flatter potential patrons. The order of the sonnets as they appeared in the publication of 1609 does not necessarily represent the order in which they have been written. In all probability they were numbered by the printer in no particular order or arrangement, but just for ease of reference. Sonnets are fourteen-line lyric poems, traditionally written in iambic pentameter - that is, in lines ten syllables long, with accents falling on every second syllable, as in Shall I compare thee to a summer's day?. Sonnets originated in Italy and were introduced to England during the Tudor period by Sir Thomas Wyatt. Shakespeare followed the more idiomatic rhyme scheme of sonnets that Sir Philip Sydney used in the first great Elizabethan sonnets cycle, Astrophel and Stella (these sonnets were published posthumously in 1591). The Shakespearean sonnets are stories about a handsome boy, or rival poet, and the mysterious and aloof "dark" lady they both love. The sonnets fall into three clear groupings: Sonnets 1 to 126 are addressed to, or concern, a young man; Sonnets 127-152 are addressed to, or concern, a dark lady (dark in the sense of her hair, her facial features, and her character), and Sonnets 153-154 are fairly free adaptations of two classical Greek poems. The most popular of the Shakespeare Sonnets are Sonnets 018 (Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day), 029 (When in disgrace with fortune), 116 (Let me not to the marriage of true minds), 126 (O thou my lovely boy) and 130 (My Mistress’ eyes). Below you find two examples: Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day Shall I compare thee to a summer's day? Thou art more lovely and more temperate: Rough winds do shake the darling buds of May, And summer's lease hath all too short a date: Sometime too hot the eye of heaven shines, And often is his gold complexion dimm'd; And every fair from fair sometime declines, By chance or nature's changing course untrimm'd; But thy eternal summer shall not fade Nor lose possession of that fair thou owest; Nor shall Death brag thou wander'st in his shade, When in eternal lines to time thou growest: So long as men can breathe or eyes can see, So long lives this and this gives life to thee. My Mistress’ Eyes My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun; Coral is far more red than her lips' red; If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun; If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head. I have seen roses damask'd, red and white, But no such roses see I in her cheeks; And in some perfumes is there more delight Than in the breath that from my mistress reeks. I love to hear her speak, yet well I know That music hath a far more pleasing sound; I grant I never saw a goddess go; My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground: And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare As any she belied with false compare.