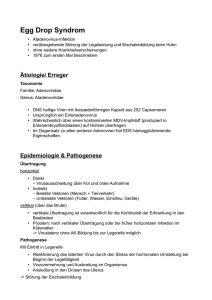

Das" Metabolovirus" HBV: Auswirkungen einer chronischen

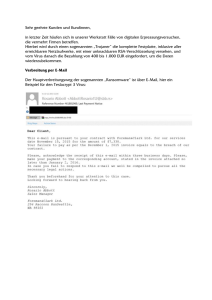

Werbung