Clinic. suspected nosocomial pneumonia

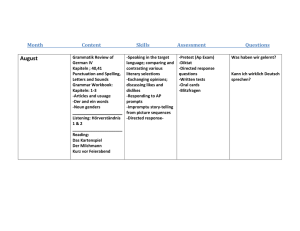

Werbung

Diagnostik und Therapie der Beatmungspneumonien M. Raffenberg, H. Lode Zentralklinik Emil von Behring, Berlin-Zehlendorf Lungenfachklinik Heckeshorn akadem. Lehrkrankenhaus der FU Berlin Epidemiologie der Beatmungspneumonie Inzidenz: 7 - 20% bzw. 5-34/1000 Tage VAP-Rate: 1-3 % pro Beatmungstag ICU-Therapie: +6d - +13d Beatmung: +10d - +23d Letalität: 20 - 50 % Craven DE, Steger KA. Epidemiology of nosocomial pneumonia. Chest 1995:108:1S-16S Fagon JY et al. Nosocomial pneumonia and mortality among pts in ICU. JAMA 1996;275:866-9 Cook DJ et al. Incid. of and risk factors for VAP in critically ill pts. Ann Intern Med 1998;129:433-40 Fagon JY et. al. Nosocomial Pneumonia. in: Schoemaker. Crit Care Med. 4th Ed. 2000: 1572-98 The Mechanically Ventilated Patient environment other patients catheter, tube enteral nutrition nursing stuff oropharyngeal flora endogenous flora microaspiration stomach, bowel distant focus of infection lower respiratory tract air blood pneumonia mod. Francoli. CMI 1997; 3(1) Supine Body Position as a Risk Factor for Nosocomial Pneumonia in Mechanically Ventilated Patients: A Randomized Trial (I) Background: Can the incidence of nosocomial pneumonia be reduced by a semirecumbent body position in ICU-patients? Design: Prospective randomized study in 130 patients at 2 ICU in Hospital Clinic Barcelona. Methods: Analysis of clinically suspected and microbiologically confirmed nosocomial pneumonia (clinical + quantitative bacteriological criteria). Drakulovic MB, Torres A et al. Lancet 1999; 354:1851-58 Supine Position in Mechanically Ventilated Patients (II) Results: Clinic. suspected nosocomial pneumonia - semirecumbent group: 3/39 (8%) - supine group: 16/47 (34%); p = 0.003 Microbiologically confirmed pneumonia - semirecumbent group: 2/39 (5%) - supine group: 11/47 (23%); p = 0.018 Highest risk: Supine body position plus enteral nutrition: 14/28 (50%) Conclusions: Semirecumbent body position reduces frequency and risk of nosocomial pneumonia especially in patients who receive enteral nutrition. Drakulovic MB, Torres A et al. Lancet 1999; 354:1851 Infektionsraten bei nicht invasiver Beatmung Pneumonie % Ergebnisse randomisierter kontrollierter Studien 30 nicht invasive Beatmung Kontrollgruppe 25 20 15 10 5 0 Brochard 1995 n=43/42 Kramer 1995 n=16/15 Antonelli 1998 n=32/32 Wood Confalonieri 1998 1999 n=16/11 n=28/28 Antonelli 2000 n=20/20 Nava 1998 n=25/25 Ventilator-Associated Pneumonia Variables Independently Associated with VAP by Log. Regress. Analysis VariableAdjusted OR 95% Cl p OSFI > 3 10.2 4.5 - 23.0 < 0.001 Pat. age > 60 yrs. 5.1 1.9 - 4.1 0.002 Prior antibiotics 3.1 1.4 - 6.9 0.004 Pat. head position 2.91 .3 - 6.8 0.013 Kollef MH. JAMA 1993; 270:1965 Ventilator-associated Pneumonia Caused by Potentially Drug-resistant Bacteria Design: Risk factor analysis of 135 consecutive episodes of VAP in a single ICU over 25 months in terms of potentially drugresistant bacteria Technique: VAP was diagnosed by PSB and BAL Results: 77 VAP by potent. resist. bacteria 58 VAP by “other” organisms Trouillet JL, Chastre J et al. AJR CCM 1998; 157:531 Ventilator-associated Pneumonia Results: Potentially-resistant bacteria: S. aureus (MRSA), P. aeruginosa, A. baumannii, S. maltophilia Riskfactors: Duration of MV (> 7d/OR=6.0) Prior antibiotic use (OR=13.5) Prior use of broad - sp. ant. (OR=4.1) Conclusions: Considering these risk factors may provide a more rational basis for selecting the initial therapy of VAP Trouillet JL et al. AJR CCM 1998; 157:531 Characteristics of Patients Who Died from VAP Case/Age[yr]/ Sex Diagnosis pATB Microorganisms 1 / 43 / M Heart transplant Yes Aspergillus species, Candida sp. 2 / 59 / M COPD Yes Pseudomonas aeruginosa 3 / 33 / M Heart transplant Yes P. aeruginosa, S marcescens 4 / 76 / M CET Yes P. aeruginosa 5 / 75 / M Cardiogenic shock Yes Aspergillus species 6 / 62 / M CAP Yes P. aeruginosa, S. marcescens 7 / 70 / M COPD Yes Acinetobacter, A. calcoacetius 8 / 74 / M COPD Yes P. aeruginosa 9 / 71 / F COPD Yes A. calcoacetius 10 / 46 / M Asthma Yes P. aeruginosa 11 / 65 / M Cardiac surgery Yes P. aeruginosa 12 / 72 / F Pancreatitis Yes P. aeruginosa 13 / 54 / M Septic shock Yes Proteus mirabilis 17 / 51 / M Multiple trauma No S. marcescens 18 / 71 / M Thoracic surgery No P. aeruginosa Rello J et al. Chest 1993; 104:1230 Ventilator-Associated Nosocomial Pneumonia Recommendations for Diagnostic Bronchoscopic Techniques 1. Protected specimen brushing (PSB) - No wedging into a peripheral position - >103 CFU/ml significant bacterial level 2. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) - Total amount of fluid >140 ml - >104 CFU/ml significant bacterial level Controversy: Diagnostic value of PSB/BAL in patients receiving antibiotics International Consensus Conference, Memphis, May 1992. Chest 102(1) 1992 Evaluation of Diagnosis of Pneumonia Operative values of protected specimen brush (PSB) and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) in four recent studies systematically referring to histology Sensitivity [%] PSB BAL Specificity [%] PSB BAL authors year Torres 1994 36 50 50 45 Marquette 1995 58 47 89 100 Chastre 1995 82 91 89 78 Papazian 1995 42 58 95 95 Lode H et al. Crit Care Clinics 1998; 14(1):119-133 Invasive and Noninvasive Strategies for Management of Suspected Ventilator-associated Pneumonia (I) Background: Optimal management of patients with clinically suspected VAP is a controversial issue Design: Multicenter, randomized trial in 31 french ICU including 413 patients Interventions: - Invasive Management Bronchoscopy with quantitative cultures of BAL or PSB - Noninvasive Management Clinical criteria and nonquantitative analysis of endotracheal aspirates Fagon JY et al. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:621-30 Actuarial 28-day Survival Among 413 Patients Assigned to the Invasive (solid line) or Clinical (dashed line) Management Strategy Fagon JY et al. Annals of Internal Medicine 2000; 132:621-30 Invasive and Noninvasive Strategies for Management of Suspected Ventilator-associated Pneumonia (II) Measurements: - Death from any cause - Quantification of organ failure - Antibiotic use at 14 / 28 days Interventions: - Reduced mortality at day 14 (16.2% vers. 25.8%; p = 0.02) - Decreased Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessm. Score on day 3 / 7 - Decreased antibiotic use on day 14 / 28 (11.5 vers. 7.5 antib.-free days on day 28) Fagon JY et al. Ann Intern Med 2000; 132:621-30 Nosokomiale Pneumonie Diagnose und Therapie nach Singh et al (2000) Keine weitere Untersuchung, beobachten nein Klinischer Verdacht auf Infektion ja ja CPIS (clinical pulmonary infection score): > 6 Antibiotika für 10-21 Tage nein 3 Tage Ciprofloxacin Erneute Bewertung am 3. Tag: CPIS > 6 nein Ciprofloxacin absetzen Chastre J, Fagon JY (2002) AJRCCM 165:867-903 ja Als Pneumonie behandeln Nosokomiale Pneumonie Diagnose und Therapie „invasive Strategie“ Keine weiteren Untersuchungen beobachten Beobachten, anderen Herd suchen nein Klinischer Verdacht auf Infektion ja sofort PSB/BAL Beobachten, anderen Herd suchen nein Bakterienkultur positiv? Schwere Sepsis? nein nein Direktpräparat: Bakterien? ja ja gezielte AB-Therapie ja sofort gezielte AB-Therapie Bakterienkultur positiv? ja Antibiotika anpassen Chastre J, Fagon JY (2002) AJRCCM 165:867-903 nein AB fortsetzen od. anpassen, anderen Herd suchen Invasives Vorgehen: Vorteile Höhere Sicherheit bei der Diagnosestellung Durch Erregernachweis zielgerichtete Antibiotikatherapie möglich Kontaminationen mit der Flora aus den oberen Atemwegen werden vermieden Bewirkt restriktiven Einsatz von Antibiotika und dadurch eine geringere Resistenzentwicklung Weniger Todesfälle Schnellere Normalisierung von Organdysfunktionen, Geringerer Antibiotikaverbrauch Fagon et al (2000) Ann Intern Med Invasives Vorgehen: Nachteile Invasive Methoden mit Risiken behaftet Kosten Technische Grenzen der Kulturverfahren Verzögerung der initialen Antibiotikatherapie Bei einem negativen Resultat, das evtl. falsch ist, erhält der Patient keine Therapie Ergebnis erst verfügbar, wenn der Verlauf der Infektion nicht mehr beeinflusst werden kann Fagon et al (2000) Ann Intern Med Diagnosis of Nosocomial Pneumonia Nosocomial Pneumonia moderate severe VAP (sputum), serology, blood cultures, Legionella-antigen therapy progress Bronchoscopy: PSB or BAL quantitative Bacteriology of Hospital-Acquired Pneumonia Early-Onset Pneumonia Late-Onset Pneumonia Other S. Pneumoniae P. aeruginosa Anaerobic bacteria H. Influenzae Enterobacter spp. Legionella pneumophila Moraxella catarrhalis Acinetobacter spp. Influenza A and B S. aureus K. pneumoniae Respiratory syncitial virus S. marcescens E. coli Fungi Aerobic gram-negative bacilli* Other gram-negative bacilli S. aureus** Francioli et al.Clin Microbiol Infect 1997; 3(suppl 1):61-76 *in patients with risk factors, **including methicillin-resistant S. aureus Stenotrophomonas maltophilia Studie Kennzahlen • Untersuchungszeitraum: Juli 1997 bis Juni 1998 • 273 Aufnahmen auf die ITS (8 Betten) • 111 Pat. in die Studie eingeschlossen (31 w, 80 m, 58 ±13,3 J.) • 65/111 Pat. (59%) mit signifikantem Nachweis pathogener Erreger in den Untersuchungsmaterialien. • 16 Pat. (14%) mit Stenotrophomonas-Nachweis (2 w, 14 m) im Bronchialsekret (68%), Sputum (19%), Pleuraexsudat (13%) Stenotrophomonas-Infektionen auf der Intensivstation - Epidemiologie A´Court et al. : SMA verantwortlich für 5% der nosokomialen Pneumonien auf der ITS Thorax 1992,47,465-473 Ibrahim EH, Ward S, Sherman G, Kollef MH.: Vergleichende Analyse von Intensivpatienten mit early-onset und late-onset Pneumonien. 3.668 Intensivpatienten (internistisch und chirurgisch) 420 nosokomiale Pneumonien (11,5%) 235 early onset Chest 2000,117,1434-42 185 late onset pneumonia P. aeruginosa (38,4%) ORSA (21,1%) S. maltophilia (11,4%) OSSA (10,8%) Gesamtletalität: 41% Antibiotic Therapy in Nosocomial Pneumonia Monotherapy versus Antibiotic combination Lower cost Higher cost Lower risk of side-effects Possible lower risk of emergence of resistance? No antagonistic effect of antibiotics Synergistic effect No pharmacologic interactions Wider spectrum Equal efficacy? Lower antibiotic dose Antibiotic Monotherapy in HAP Reference Drugs Results (Cure/Improv.) Comments R.D. Manji et al AJM 1988 Cefoperazone versus Cefazol/Gentamycin Cefoper.: 87% Combin.: 72% Lower costs for monotherapy M.P. Fink et al AAC 1994 Ciprofloxacin versus Imipenem Ciprofloxacin: 64% Imipenem: 6% seizures Imipenem: 56% Ciprofloxacin: 1% A. Cometta etal AAC 1994 Imipenem versus Imipenem/Netilmicin Imipenem: 80% Combination: 11 Combination: 86% nephrotoxic reaction E. Rubinstein, H. Lode et al Ceftazidime versus Ceftazidime: 85% Combination: 9 Combination: 77% nephrotoxic reaction CID 1995 Ceftriaxone/Tobramycin Combination Therapy as a Tool to Prevent Emergence of Bacterial Resistance Design: Overview of experimental data analysing antimicrobial mono-versus combination therapy. Results: In vitro Pk and animal data indicate that emergence of resistance with combination therapy is less common. Problems: - Demonstrated only in P. aeruginosa infections - No strong clinical trials Mouton JW. Infection 1999 Mean Change (log values) of MIC for Ceftazidime of Pseudomonas aeruginosa During Monotherapy or Combined With Tobramycin in a in vitro Pharmacokinetic Model mean increase factor MIC 8 6 4 2 0 0h Mouton JW. 1999 8h 16 h 24 h Clinical Indications of Combinations Difficult to treat Gram-nagatives Enterobacter Pseudomonas Acinetobacter Clinical Arguments Avoid mutation Obtain synergistic effect Possible prevention of the emergence of resistance Extend the spectrum of antibacterial activities: against enterococci (using penicillin) against anaerobes (using metronidazole) Bergogne-Bérézine. Phoenix 1995 PK/PD Parameters: A First Sight • Peak • Through • Area under the curve concentration Serum Concentration varying with time peak area under the curve through time AUIC Prediction of Clinical and Microbiological Outcome in RTI Forrest A et al. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993;37:1073-1081 Pharmacodynamic Evaluation of Factors Associated With the Development of Bacterial Resistance in Acutely Ill Patients During Therapy Design: Analysis of 107 pat. suffering from LRTI; 128 pathogens and 5 antimicrobial regimes. Parameters: - MIC - before/after treatment - AUC 0-24 - PK/PD model (Hill equation) Thomas JK et al. AAC 1998; 42:521-27 AUIC versus Resistance Thomas JK et al. AAC 1998 Scheduled Change of Antibiotic Classes (I) A strategy to decrase the incidence of ventilator-associated pneumonia Study design: Prospective before - after study Patients: 680 with cardiac surgery Location: ICU-St. Louis, Missouri Barnes-Jewish Hospital (900 beds) Intervention: During 12-months period (8/95-8/96) empiric treatment - first 6-months period: ceftazidime - second 6-months period: ciprofloxacin Kollef MH. AJRCCM 1997; 156:1040 VAP (all etiologies) 12 10 VAP (due to ARGNB) 11,6 8 6 4 6,7 4 2 0,9 0 Before-Period Kollef et al.AJRCCM 1997:165:1040-48 After-Period Scheduled Change of Antibiotic Classes (II) Results Incidence of VAP: Before 11.6% (n = 327) After 6.7% (n = 353) VAP with resist. GNB: 4.0% versus 0.9% Bacteremia due to ARGNB: 1.7% versus 0.3% Conclusion: These data suggest that a scheduled change of antibiotic classes can reduce the incidence of VAP attributed to ARGNB. Kollef MH. AJRCCM 1997; 156:1040 Classifying Patients With Hospital-acquired Pneumonia Severity of illness severe mild to moderate no risk factors with risk factors with risk factors onset any time onset any time early onset late onset onset any time Group 1 Group 2 Group 1 Group 3 Group 3 no risk factors Consensus Statement of the American Thoracic Society: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153:1711-1725 Patients with mild to moderate hospital-acquired Group 1 pneumonia, no unusual risk factors, onset any time or patients with severe hospital acquired pneumonia with early onset* Core organisms Core antibiotics Enteric gram-negative bacilli (Non-Pseudomonal) Enterobacter spp. generation E. coli Klebsiella spp. Proteus spp. Serratia marcescens Haemophilus influenzae S. aureus (Methicillin-sensitive) Streptococcus pneumoniae Cephalosporin second generation or Nonpseudomonal third Beta-lactam / beta-lactamaseinhibitor combination If allergic to penicillin: Fluoroquinolone or Clindamycin + aztreonam *Excludes patients with immunosuppression Consensus Statement of the American Thoracic Society: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153:1711-1725 Group 2 Patients with mild to moderate hospital-acquired pneumonia, with risk factors, onset any time* Core organisms plus: Core antibiotics plus: Anaerobes (recent abdomial surgery) lactamasewitnessed aspiration) Staphylococcus aureus (coma, head trauma, diabetes mellitus, renal failure) Legionella (high dose steroids) Pseudomonas aeruginosa (prolonged ICU stay, steroids, antibiotics, structural lung disease) Clindamycin or beta-lactam / betainhibitor (alone) +/- Vancomycin (until methicillin- resistant S. aureus is ruled out) Erythromycin +/- Rifampicin ** Treat as severe hospital-acquired pneumonia (Group 3) *Excludes patients with immunosuppression; ** Rifampicin may be added if Legionella species is documented Consensus Statement of the American Thoracic Society: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153:1711-1725 Group 3 Patients with severe hospital-acquired pneumonia, with risk factors, early onset or patients with severe hospital acquired pneumonia with late onset* Core organisms plus: Therapy P. aeruginosa Acinetobacter spp. Consider MRSA Aminoglycoside or ciprofloxacin plus one of the following: Antipseudomonal penicillin beta-lactam / beta-lactamase inhibitor Ceftazidime or cefoperazone Imipenem Aztreonam** +/- Vancomycin *Excludes patients with immunosuppression ** Aztreonam efficacy is limited to enteric gram-negative bacilli and should not be used in combination with aminoglycoside if gram-positive or H. influenzae infection is of concern Consensus Statement of the American Thoracic Society: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 153:1711-1725