Infos

Werbung

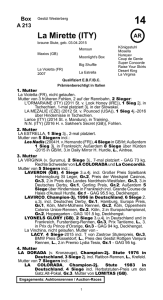

Leningrader Blockade (russ.: блокада Ленинграда) Teil von: Zweiter Weltkrieg, Krieg gegen die Sowjetunion 1941–1945 Die Ostfront zu Beginn der Belagerung von Leningrad Datum Ort Ausgang 8. September 1941–27. Januar 1944 Leningrad, Sowjetunion Sieg der Sowjetunion Konfliktparteien Achsenmächte Sowjetunion Befehlshaber Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb Kliment Woroschilow Georg von Küchler Georgi Schukow Truppenstärke 725.000 Soldaten 930.000 Soldaten Verluste unbekannt 16.470 Zivilisten durch Bombenangriffe und ca. 1.000.000 Zivilisten durch Unterernährung Bedeutende Militäroperationen während des Deutsch-Sowjetischen Krieges 1941: Białystok-Minsk – Dubno-LuzkRiwne – Smolensk – Uman – Kiew – Odessa – Leningrader Blockade – Rostow – Wjasma-Brjansk – Moskau 1942: Charkow – Operation Blau – Operation Braunschweig – Operation Edelweiß – Stalingrad – Operation Mars 1943: Woronesch-Charkow – Operation Iskra – Nordkaukasus – Charkow – Unternehmen Zitadelle – Smolensk – Dnepr 1944: Dnepr-Karpaten-Operation – Leningrad-Nowgorod – Krim – Wyborg– Petrosawodsk – Weißrussland – LwiwSandomierz – Iaşi–Chişinău – Belgrad – Petsamo-Kirkenes – Baltikum – Karpaten – Budapest 1945: Weichsel-Oder – Ostpreußen – Westkarpaten – Ostpommern – Plattensee – Oberschlesien – Wien – Berlin – Prag Als Leningrader Blockade (russisch: блокада Ленинграда) bezeichnet man die Belagerung Leningrads durch die deutsche Heeresgruppe Nord und finnische Truppen während des Zweiten Weltkrieges. Sie dauerte vom 8. September 1941 bis zum 27. Januar 1944. Schätzungen gehen von etwa 1,1 Millionen zivilen Bewohnern der Stadt aus, die in Folge der Blockade ihr Leben verloren. Der beabsichtigte Verzicht auf eine Einnahme der Stadt durch die deutschen Truppen, mit dem Ziel, die Leningrader Bevölkerung systematisch verhungern zu lassen, war eines der eklatantesten Kriegsverbrechen der deutschen Wehrmacht während des Krieges gegen die Sowjetunion.[1] Deutsche Offensive [Bearbeiten] Am 27. Juni 1941 entschied der Leningrader Rat der Deputierten des werktätigen Volkes, Tausende Menschen zur Anlage von Befestigungen zu mobilisieren. Mehrere Verteidigungsstellungen wurden gebaut. Eine verlief von der Mündung der Luga über Tschudowo, Gattschina, Urizk, Pulkowo zur Newa. Eine zweite verlief von Peterhof nach Gattschina, Pulkowo, Kolpino und Koltuschi. Eine dritte Stellung gegen die Finnen wurde in den nördlichen Vorstädten Leningrads gebaut. Insgesamt wurden 190 Kilometer Balkensperren, 635 Kilometer Stacheldrahtverhaue, 700 Kilometer Panzergräben, 5000 ErdHolz-Stellungen und Stahlbeton-Artilleriestellungen sowie 25.000 Kilometer Schützengräben von Zivilisten angelegt. Ein Geschütz des Kreuzers Aurora wurde auf den Pulkowskij-Höhen südlich von Leningrad installiert. Nachdem die sowjetischen Truppen der Nordwestfront Ende Juni im Baltikum großteils vernichtet worden waren, erzwang die Wehrmacht den Weg nach Ostrow und Pskow. Am 10. Juli waren beide Städte eingenommen und die Wehrmacht hatte Kunda und Kingissepp erreicht. Daraufhin rückten sie von Narwa, der Luschkij-Region und vom Südosten nach Leningrad, sowie nördlich und südlich des Ilmensees vor, um Leningrad vom Osten abzuschneiden und sich mit den finnischen Truppen auf dem Ostufer des Ladogasees zu verbinden. Der Artilleriebeschuss der Stadt begann am 4. September. Die Bombardierung am 8. September verursachte 178 Brände. Anfang Oktober verzichteten die Deutschen jedoch auf den weiteren Angriff auf die Stadt: Nachdem die Masse der sowjetrussischen Wehrmacht auf dem Hauptkriegsschauplatz zerschlagen oder vernichtet ist, liegt kein zwingender Grund mehr vor, russische Kräfte in Finnland durch Angriff zu fesseln. Um vor Eintritt des Winters Murmansk … zu nehmen oder … die Murmanbahn abzuschneiden, reichen die Stärke und die Angriffskraft der verfügbaren Verbände und die fortgeschrittene Jahreszeit nicht mehr aus. (Weisung Nr. 37 vom 10. Oktober 1941). Die Fortsetzung der Angriffe wurde für das Frühjahr 1942 geplant, danach aber aufgrund von logistischen Problemen immer weiter verschoben. Finnische Offensive [Bearbeiten] Im August, zu Beginn des Fortsetzungskrieges, hatten die Finnen den Isthmus von Karelien zurückerobert und rückten östlich des Ladogasees durch Karelien weiter vor, wodurch sie nun Leningrad im Westen und Norden bedrohten. Die finnischen Truppen hielten jedoch an der alten finnisch-russischen Grenze von 1939. Das finnische Hauptquartier wies deutsche Bitten um Luftangriffe gegen Leningrad zurück und rückte nicht weiter südlich über den Swir (160 Kilometer nordöstlich Leningrads) ins besetzte Ostkarelien vor. Der deutsche Vormarsch war dagegen sehr rasch und im September schlossen die deutschen Truppen Leningrad ein. Am 4. September reiste General der Artillerie Jodl zum finnischen Hauptquartier, um den Oberkommandierenden Mannerheim zu überreden, die finnische Offensive fortzusetzen. Mannerheim lehnte dieses Ansinnen ab. Nach dem Krieg sagte der frühere finnische Präsident Ryti: „Ich besuchte am 24. August 1941 das Hauptquartier von Marschall Mannerheim. Die Deutschen forderten uns auf, die alte Grenze zu überschreiten und die Offensive gegen Leningrad fortzusetzen. Ich sagte, daß die Eroberung Leningrads nicht unser Ziel sei und wir uns nicht daran beteiligen sollten. Mannerheim und der Kriegsminister Walden stimmten mir zu und lehnten die Angebote der Deutschen ab. Das Ergebnis war eine paradoxe Situation: die Deutschen waren nicht in der Lage, sich Leningrad von Norden zu nähern…“ Später wurde außerdem geltend gemacht, dass aus dem finnischen Territorium kein systematischer Artilleriebeschuss oder Luftangriffe vorgetragen worden wären. Belagerung [Bearbeiten] Lebensmittelkarte für Brot in Leningrad, 125-Gramm-Rationen, 1941 Mit der Schließung des Blockaderings wurden alle Versorgungslinien für die Millionenstadt abgeschnitten und die Versorgung war nur noch über den Ladogasee möglich. Allerdings war diese Route für die Erfordernisse der Stadt nicht ausgebaut, da es keine Anlegestelle und keine Zufahrtsstraßen gab. Die Parteikader Alexei Kusnezow und Pjotr Popkow waren für die Organisation des zivilen Lebens und die Verteilung der Nahrungsmittel innerhalb der Stadt zuständig. Sie ordneten den Bau provisorischer Zufahrtswege zum Westufer des Ladoga-Sees an. Luftangriffe [Bearbeiten] Die ersten Bombardements auf die Stadt erfolgten am 8. September. Dabei fielen 5000 Brandbomben auf den Moskowskij Rajon, 1311 weitere auf den Smolnij Rajon mit dem Regierungsgebäude und 16 auf den Krasnogwardejskij Rajon. Ab sofort erfolgten täglich schwere Angriffe auf die Stadt. Ganze Wohngebiete wurden schwer beschädigt (Awtowo, Moskowskij, Frunsenskij). Schwere Angriffe waren gegen das Kirow-Werk gerichtet, den größten Betrieb der Stadt, der von der Front nur drei Kilometer entfernt war. Gezielt wurden von der deutschen Luftwaffe die Badajew-Lagerhäuser beschossen, in denen ein Großteil der Lebensmittelvorräte der Stadt gelagert war. 3000 Tonnen Mehl und 2500 Tonnen Zucker verbrannten. Wochen nach Beginn der schweren Hungerkatastrophe wurde die süße Erde, in die der geschmolzene Zucker gelaufen war, zu hohen Preisen auf dem Schwarzmarkt verkauft Die deutsche Luftwaffe griff gezielt Kindergärten, Schulen, Betriebe, Straßenbahnhaltestellen an, um die Menschen zu demoralisieren und nutzte dabei als Orientierungspunkte die Schornsteine und hohen historischen Gebäude der Stadt (Isaakskathedrale, Admiralität, Peterund-Paul-Festung). Die deutsche Luftwaffe warf auf die Stadt insgesamt rund 100.000 Fliegerbomben ab. [2] Hunger [Bearbeiten] Am 2. September 1941 wurden die Nahrungsmittelrationen reduziert. Am 8. September wurde zusätzlich eine große Menge an Getreide, Mehl und Zucker durch deutsche Luftangriffe vernichtet, was zu einer weiteren Verschärfung der Ernährungssituation führte. Am 12. September wurde berechnet, dass die Rationen für Armee und Zivilbevölkerung für die folgende Zeit ausreichen würden: Getreide und Mehl – für 35 Tage; Grütze und Makkaroni – für 30 Tage; Fleisch (inklusive Viehbestand) – für 33 Tage; Fette – für 45 Tage; Zucker und Süßwaren – für 60 Tage. Der Abverkauf der Waren erfolgte sehr schnell, da die Menschen Vorräte anlegten. Restaurants und Delikatessläden verkauften weiterhin ohne Karten und nicht zuletzt auch deshalb gingen die Vorräte dem Ende entgegen. Zwölf Prozent aller Fette und zehn Prozent des Fleisches des städtischen Gesamtkonsums wurden so verbraucht. Am 20. November wurden die Rationen nochmals reduziert [3]. Arbeiter erhielten 500 Gramm Brot, Angestellte und Kinder 300 Gramm, andere Familienangehörige 250 Gramm. Die Ausgabe von Mehl und Grütze wurde ebenfalls reduziert, aber gleichzeitig die von Zucker, Süßwaren und Fetten erhöht. Die Armee und die Baltische Flotte hatten noch Bestände an Notrationen, die aber nicht ausreichten. Die zur Versorgung der Stadt eingesetzte LadogaFlottille war schlecht ausgerüstet und von deutschen Flugzeugen bombardiert worden. Mehrere mit Getreide beladene Lastkähne waren so im September versenkt worden. Ein großer Teil davon konnte später von Tauchern gehoben werden. Dieses feuchte Getreide wurde später zum Brotbacken verwendet. Nachdem die Reserven an Malz zur Neige gegangen waren, wurde es durch aufgelöste Zellulose und Baumwolle ersetzt. Auch der Hafer für die Pferde wurde gegessen, während die Pferde mit Laub gefüttert wurden. Nachdem 2000 Tonnen Schafsinnereien im Hafen gefunden worden waren, wurde daraus eine Gelatine hergestellt. Später wurden die Fleischrationen durch diese Gelatine und Kalbshäute ersetzt. Während der Blockade gab es insgesamt fünf Lebensmittelreduzierungen. Trotz der Beimischung verschiedener Ersatzstoffe zum Brot (Kleie, Getreidespelzen und Zellulose) reichten die Vorräte nicht aus und mit der Kürzung der Brotration am 1. Oktober begann die Hungersnot, Arbeiter erhielten zu diesem Zeitpunkt 400 Gramm und alle anderen 200 Gramm. Mitte Oktober litt bereits ein Großteil der Bevölkerung am Hunger. Im Winter 1941/1942 verloren die Menschen bis zu 45 Prozent ihres Körpergewichtes. Die Folge war, dass die Körper begannen, Muskelmasse zu verbrennen und Herz und Leber zu verkleinern. Die Dystrophie (Unterernährung) wurde zur Haupttodesursache. Es begann das Massensterben. Opfer der Zivilbevölkerung [Bearbeiten] Die folgende Tabelle gibt die Anzahl der monatlichen Todesfälle während des ersten Jahrs der Belagerung wieder. Monat Juni Oktober November Dezember Januar Februar 1941 1941 1941 1941 1942 1942 Todesopfer 3.273 6.199 9.183 39.073 96.751 96.015 März 1942 April 1942 Mai 1942 Juni 1942 keine 64.294 49.794 33.668 Angaben Insgesamt starben von Juni 1941 bis Juni 1942 etwa 470.000 Menschen. Die Menschen richteten ihre gesamte Energie auf die Nahrungssuche. Gegessen wurde alles, was organischen Ursprunges war, wie Klebstoff, Schmierfett und Tapetenkleister. Lederwaren wurden ausgekocht und im November 1941 gab es in Leningrad weder Katzen oder Hunde noch Ratten und Krähen. Die Not führte zu einer Auflösung der öffentlichen Ordnung: Petr Popkow erzählte dem Militärberichterstatter Tschakowski, dass er neben der Nahrungsmittelversorgung seine Hauptaufgabe im Kampf gegen Plünderer und Marodeure sehe.[4] Es traten die ersten Fälle von Kannibalismus auf. Insgesamt wurden dem NKWD bis zum Februar 1942 1025 Fälle bekannt. Kinderschlitten wurden zum einzigen Transportmittel. Mit ihnen wurden Wasser, Brot und Leichen transportiert. In den Straßen lagen Leichen; Menschen brachen auf der Straße zusammen und blieben einfach liegen. Der Tod wurde zur Normalität. In den eiskalten Wohnungen lebten die Menschen zusammen mit ihren toten Angehörigen, die nicht beerdigt wurden, weil der Transport zum Friedhof für die entkräfteten Menschen zu beschwerlich war. Spezielle Komsomolzenbrigaden, die aus meist jungen Frauen bestanden, durchsuchten täglich hunderte von Wohnungen nach Waisenkindern, doch oft lebte in den Wohnungen niemand mehr. Die Gesamtzahl der Opfer der Blockade ist immer noch umstritten. Nach dem Krieg meldete die sowjetische Regierung 670.000 Todesfälle in der Zeit vom Beginn 1941 bis Januar 1944, wovon die meisten durch Unterernährung und Unterkühlung verursacht worden waren. Einige unabhängige Schätzungen gaben viel höhere Opfernzahlen an, die von 700.000 und 1.500.000 reichen. Die meisten Quellen gehen aber von einer Zahl von etwa 1.100.000 Toten aus. Leben in der belagerten Stadt [Bearbeiten] Zwar wurden bis zum Winter 1941/1942 etwa 270 Betriebe und Fabriken geschlossen, aber das riesige Kirow- und Ishorskij-Werk und die Admiraltejskij-Werft arbeiteten weiter. Auch die Hochschulen und wissenschaftlichen Institute blieben geöffnet. 1000 Hochschullehrer unterrichteten im Blockadewinter und 2500 Studenten schlossen ihr Studium ab. 39 Schulen hielten den Lehrbetrieb aufrecht. 532 Schüler beendeten die 10. Klasse. Strom und Energie [Bearbeiten] Wegen mangelnder Stromversorgung mussten viele Fabriken geschlossen werden und im November wurde der Betrieb der Straßenbahnen eingestellt. Mit Ausnahme des Generalstabs, des Smolnij, der Distriktausschüsse, der Luftabwehrstellungen und ähnlicher Institutionen war die Nutzung von Strom überall verboten. Ende September waren alle Reserven an Öl und Kohle verbraucht. Die letzte Möglichkeit zur Energiegewinnung war, die verbliebenen Bäume im Stadtgebiet zu fällen. Am 8. Oktober beschlossen der Exekutivausschuss von Leningrad (Ленгорисполком) und der regionale Exekutivausschuss (облисполком), mit dem Holzeinschlag in den Distrikten Pargolowo und Wsewolschskij im Norden der Stadt zu beginnen. Es gab jedoch weder Werkzeug noch Unterkünfte für die aus Jugendlichen gebildeten Holzfällergruppen, die aus diesem Grund nur geringe Mengen an Holz liefern konnten. Straße des Lebens [Bearbeiten] → Hauptartikel: Straße des Lebens Im Chaos des ersten Kriegswinters war kein Evakuierungsplan vorhanden, weshalb die Stadt und ihre Außenbezirke bis zum 20. November 1941 in vollständiger Isolation hungerte. Zu diesem Zeitpunkt wurde die als Straße des Lebens (offiziell: „Militärische Autostraße Nummer 101―) bezeichnete Eisstraße über den zugefrorenen Ladogasee eröffnet. Die über die Straße herangeschafften Lebensmittel reichten aber bei weitem nicht aus, alle Einwohner der Stadt zu versorgen. Immerhin gelang es, über die Straße eine große Anzahl von Zivilisten zu evakuieren. In den Sommermonaten des Jahres 1942 wurde die Versorgungsroute mit Hilfe von Schiffen aufrecht erhalten. Nach der Schaffung eines schmalen Landkorridors am südlichen Ufer des Ladoga-Sees im Januar 1943 schwand die Bedeutung des Weges über den See, obgleich er bis zum Ende der Belagerung im Januar 1944 in Benutzung blieb. Sowjetische Entsatzangriffe [Bearbeiten] Bereits im Januar 1942 wurde eine erste sowjetische Gegenoffensive zur Überwindung der Blockade eingeleitet. (→Ljubaner Operation) Diese scheiterte jedoch bereits im Ansatz an schlechter Planung durch die sowjetischen Befehlshaber, nicht vorhandener Tarnung sowjetischer Angriffsformationen und einer gut organisierten Abwehr durch die Armeen der deutschen Heeresgruppe Nord.[5] Nach verlustreichen Angriffen wurde die Offensive im April 1942 beendet. Ein deutscher Gegenangriff im Juni 1942 führte zur Vernichtung der sowjetischen 2. Stoßarmee in einem Kessel. Ein weiterer Versuch der Roten Armee, die Blockade zu beenden, wurde im August 1942 mit der Sinjawinsker Operation unternommen. Auch dieser in der deutschen Geschichtsschreibung Erste Ladoga-Schlacht bezeichnete Angriff endete im Oktober 1942 mit einem ähnlichen Ergebnis wie zuvor die Ljubaner Operation. Die vollständige Blockade dauerte noch bis zum 12. Januar 1943, dem Tag, an dem mit der Operation Iskra ein weiterer Großangriff von Truppen der Leningrader und der WolchowFront gestartet wurde. Nach schweren Kämpfen überwanden Einheiten der Roten Armee die starken deutschen Befestigungen südlich des Ladogasees und am 18. Januar trafen die Leningrad- und die Wolchow-Front aufeinander. Ein Landkorridor in die Stadt war geöffnet, der jedoch noch in der Reichweite deutscher Artillerie lag. Im Juli 1943 startete die Rote Armee erneut eine Offensive mit dem Ziel die Belagerung der Stadt vollständig zu beenden. Dieser in der deutschen Militärgeschichtsschreibung als Dritte Ladoga-Schlacht bekannte Angriff führte nur zu geringen Geländegewinnen für die sowjetische Armee, die unter unverhältnismäßig hohen Verlusten erkauft wurden. Die dramatische Lage der deutschen Truppen an anderen Frontabschnitten führte im Herbst 1943 auch zu einer Schwächung der Leningrad belagernden deutschen Heeresgruppe Nord, die Einheiten an andere Großverbände abgeben und zusätzliche Frontabschnitte verteidigen musste. Diese Reduzierung der deutschen Kampfkraft und ein wesentlich verbesserter Angriffsplan der Roten Armee führten wenig später zum Rückzug der Deutschen. Im Januar 1944 wurde die Belagerung während der Leningrad-Nowgoroder Operation aufgehoben, als es den sowjetischen Truppen gelang, aus dem Brückenkopf Oranienbaum heraus die starken deutschen Verteidigungslinien von hinten zu durchbrechen. Sechs Monate später wurden die Finnen schließlich auf die andere Seite der Bucht von Wyborg und des Flusses Wuoksi zurückgeworfen. (→Wyborg-Petrosawodsker Operation) Darstellung der Blockade [Bearbeiten] Nach dem Ende des Krieges wurde die Leningrader Blockade schnell zum Gegenstand unterschiedlichster kultureller und wissenschaftlicher Darstellungen. Geschichtswissenschaft in Deutschland [Bearbeiten] Der Versuch, die deutschen Motive für die Durchführung und Art der folgenschweren Belagerung von Leningrad herauszuarbeiten und zu bewerten, hat in der deutschen Geschichtswissenschaft kontroverse Ergebnisse hervorgebracht. Umstritten ist dabei vor allem die Frage, wie das deutsche Vorgehen völkerrechtlich und moralisch zu bewerten sei. Vor allem ältere (west-)deutsche Forschungen haben häufig einerseits, zum Teil basierend auf nach dem Krieg entstandenen Darstellungen von Wehrmachtsoffizieren, Hitler persönlich die hauptsächliche Schuld zugewiesen. Der Diktator habe die Belagerung aus Hass und Verachtung gegenüber dem traditionellen kulturellen Zentrum des zaristischen Russland wie gegenüber der Wiege der bolschewistischen Revolution befohlen. Andererseits wird in diesen Darstellungen aber betont, dass die Strategie der Belagerung von Städten nicht ungewöhnlich, vielmehr in der Kriegshistorie häufig angewendet worden sei. In diesem Sinne könne zwar die hohe Anzahl von Opfern im Falle Leningrads als besonders tragisch betrachtet werden, jedoch nicht von einem Bruch mit gängiger militärischer Praxis und daher auch nicht von einem eine moralische Verurteilung der Wehrmacht legitimierenden Kriegsverbrechen die Rede sein. Hauptmotiv der Deutschen, auf eine militärische Eroberung der Stadt zu verzichten und stattdessen den Versuch zu unternehmen, diese durch Aushungern zur Aufgabe zu zwingen, sei nach diesen Interpretationen die Furcht vor dem erwarteten Widerstand von Roter Armee und Freischärlern und vor einem daraus folgenden, erbitterten und verlustreichen Straßenkampf gewesen. Eine wichtige Rolle hätten bei der Entscheidung Ende August, Anfang September 1941 aktuelle taktische Erwägungen, weniger langfristige Kriegsziele gespielt. Demgegenüber setzt die jüngere deutsche Forschung die Belagerung Leningrads häufiger in den Kontext eines von den Nationalsozialisten in bewusstem Bruch mit Kriegs- und Völkerrechtstraditionen durchgeführten Vernichtungskrieges. Mit dessen Zielen und Praktiken hätten sich die meisten höheren Wehrmachtsoffiziere identifiziert. Auch die konkrete Entscheidung für die Belagerung Leningrads sei nicht nur aus kriegstaktischen Gründen erfolgt. Verantwortlich sei vielmehr eine strategische Umorientierung nach dem bald zutage tretenden Scheitern des Blitzkrieg-Konzeptes im Falle der Sowjetunion gewesen, was eine Reduktion von eigenen Operationen und Risiken notwendig gemacht habe. In der Folge setzte sich demnach unter den deutschen Militärs schnell eine Rhetorik durch, in der die komplette Vernichtung der Stadt und ihrer Bevölkerung zum eigentlichen Ziel der Belagerung erhoben wurde. In einer Fachstudie bezeichnete der Historiker Jörg Ganzenmüller im Jahr 2005 den blockadebedingten Tod von Hunderttausenden von Leningradern so als von den Deutschen gezielt herbeigeführten „Genozid―, basierend auf einer „rassistisch motivierten Hungerpolitik―. [6] Sowjetische Literatur [Bearbeiten] In den Jahren, die kurz auf die Blockade folgten, wurde die grausame Realität der Leiden der Leningrader Bevölkerung in der sowjetischen Literatur ungeschönt und wirklichkeitsnah wiedergegeben. Alexander Tschakowski, Olga Bergholz, Iwan Kratt oder Wera Inber gehören zu den heute bekannten Autoren von Werken über die Leningrader Blockade. Nachdem jedoch Alexei Kusnezow und Pjotr Popkow 1949 während der Leningrader Affäre verhaftet und hingerichtet worden waren, begann auch die Säuberung der sowjetischen Literatur über die Blockade. Eingezogen oder vernichtet wurden Bücher, die eine viel zu „aufrichtige und grausame― Darstellung der Leiden der Leningrader Bevölkerung enthielten oder das Verhalten der Leningrader ―unpatriotisch‖ und ―ideologielos‖ schilderten. Die Zensur allzu realitätsnaher Berichte über die Blockade hielt in der Sowjetunion bis in die 1980er Jahre hinein an. Statt dessen wurden nur patriotisch überhöhte und parteiideologisch korrekte Werke zugelassen.[7] Erst nach dem Ende der Sowjetunion konnten seriöse Schilderungen der Blockade in Russland ungehindert verbreitet werden. Einflüsse auf die Kultur [Bearbeiten] Der Belagerung von Leningrad wurde in den späten 1950er-Jahren durch den Grüngürtel des Ruhmes gedacht, einem Band von Bäumen und Denkmälern entlang des früheren Frontverlaufs. Leningrad wurde als erster Stadt der Sowjetunion der Titel Heldenstadt verliehen. Dmitri Schostakowitsch schrieb seine Siebente, die Leningrader Symphonie. Ich widme meine Siebente Sinfonie unserem Kampf gegen den Faschismus, unserem unabwendbaren Sieg über den Feind, und Leningrad, meiner Heimatstadt ... (Schostakowitsch am 19. März 1942 in der Prawda). 2003 publizierte die US-Autorin Elise Blackwell „Hunger―: einen Roman über die Ereignisse am Rande der Belagerung. Der amerikanische Sänger Billy Joel schrieb ein Lied mit dem Titel „Leningrad―, das sich auf die berühmte Blockade bezog. Das Lied handelt zum Teil von einem jungen Russen namens Viktor, der seinen Vater während der Einschließung verlor. In dem Buch Stadt der Diebe des amerikanischen Autors David Benioff werden die Geschehnisse während der Belagerung der Stadt behandelt. Siehe auch [Bearbeiten] Tanja Sawitschewa Daniil Charms Literatur [Bearbeiten] Jörg Ganzenmüller: Das belagerte Leningrad 1941-1944. Die Stadt in den Strategien von Angreifern und Verteidigern. Ferdinand Schöningh, Paderborn 2005. ISBN 3-506-72889-X Leon Gouré: The Siege of Leningrad. Stanford: Stanford UP, 1962. Gerhart Hass: Die deutsche Historiografie und die Belagerung Leningrads (1941–1944), Zeitschrift für Geschichtswissenschaft 54.2 (2006), 139-162. Werner Haupt: Leningrad - Die 900-Tage-Schlacht, 1941–1944. Friedberg: Podzun-PallasVerlag, 1980. ISBN 3-7909-0132-6 Peter Jahn (Hrsg.): Blockade Leningrads – Блокада Ленинграда. Berlin: Links, 2004. Antje Leetz, Barbara Wenner: Blockade, Leningrad 1941–1944 – Dokumente und Essays von Russen und Deutschen. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt, 1992. William Lubbeck, David B. Hurt: At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North. Philadelphia, PA: Casemate, 2006 (hardcover, ISBN 1-932033-55-6). Dimitrij W. Pawlow: Die Blockade von Leningrad 1941. Frauenfeld und Stuttgart: Huber, 1967. Harrison E. Salisbury: 900 Tage: Die Belagerung von Leningrad. Frankfurt a.M.: S.Fischer, 1970. Ella Foniakowa: Das Brot jener Jahre: Ein Kind erlebt die Leningrader Blockade. Stuttgart und Berlin: Mayer, 2000. Jaap ter Haar: Oleg oder Die belagerte Stadt. München: dtv junior, 1977. ISBN 3-423-07858-8 Gennadi Gor: Blockade. Gedichte. [1942–1944]. Russisch / deutsch. A. d. Russ von Peter Urban. Wien: Edition Korrespondenzen 2007. ISBN 978-3-902113-52-8 Alexander Tschakowski: Die Blockade. Berlin: Verlag Volk und Welt, 1975 (aus dem Russischen von Harry Burck) Arlen Wiktorowitsch Bljum: Das Thema der Leningrader Blockade unter der Blockade der Zensur - aus Archivdokumenten der Glawlit der UdSSR, Zeitschrift Newa Nr. 1 2004, S. 238245 (russisch, online) Weblinks [Bearbeiten] Artikel zum 60. Jahrestag des Durchbruchs der Blockade in der Wochenzeitung „Die Zeit“ Informationen zur Straßenbahn während der Blockade [2] Deutsche Wochenschau No. 577 1941 – Vor Leningrad Die Blockade Leningrads – Fakten und Mythen einer russischen Kriegstragödie Einzelnachweise [Bearbeiten] 1. ↑ Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung: Verbrechen der Wehrmacht - Dimensionen des Vernichtungskrieges 1941-1944, Ausstellungskatalog der korrigierten Fassung der Wehrmachtsausstellung, Hamburger Edition 2002, ISBN 3-930908-74-3, S.308 2. ↑ http://findarticles.com/p/articles/mi_m1310/is_1985_May/ai_3752759 3. ↑ [1] 4. ↑ A.B. Tschakowski: Die Blockade, S.96 5. ↑ David M. Glantz: Soviet Military Deception in the Second World War, Verlag Frank Cass New York, ISBN 0-7146-3347-X, S.68-71 6. ↑ Jörg Ganzenmüller, Das belagerte Leningrad (siehe Literaturliste), S.13-82, Zitate S. 17 und 20. 7. ↑ Arlen Bljum: Das Thema der Leningrader Blockade unter der Blockade der Zensur - aus Archivdokumenten der Glawlit der UdSSR, Zeitschrift Newa Nr. 1 2004, S. 238-245, online Von „http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leningrader_Blockade“ Kategorien: Militärische Operation im Krieg gegen die Sowjetunion 1941–1945 | Sankt Petersburg | Belagerung | 1941 | 1942 | 1943 | 1944 Siege of Leningrad From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jump to: navigation, search Siege of Leningrad Part of the Eastern Front of World War II Diorama of the Siege of Leningrad, in the Museum of the Great Patriotic War, in Moscow Date September 8, 1941 - January 27, 1944 Location Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union Result Soviet victory Belligerents Germany Finland[1][2][3] Italy[4] Soviet Union Commanders W.R. von Leeb Georg von Küchler C.G.E. Mannerheim[5][6] Kliment Voroshilov Georgy Zhukov Leonid Govorov Strength 725,000[citation needed] 930,000[citation needed] Casualties and losses Axis troops unknown Red Army:[7] 1,017,881 killed, captured or missing 2,418,185 wounded and sick Civilians:[7] 642,000 during the siege, 400,000 at evacuations [show] v•d•e Eastern Front [show] v•d•e Leningrad and the Baltics 1941–1944 [show] v•d•e Operation Barbarossa The Siege of Leningrad, also known as the Leningrad Blockade (Russian: блокада Ленинграда, transliteration: blokada Leningrada) was a prolonged military operation by the German Army Group North and the Finnish Defence Forces to capture Leningrad in the Eastern Front theatre. It started on 8 September 1941, when the last land connection to the city was severed. Although the Soviets managed to open a narrow land corridor to the city on 18 January 1943, the total lifting took place on 27 January 1944, 872 days after it began. It was one of the longest and most destructive sieges in history and the most costly in terms of casualties.[8] [edit] Background The capture of Leningrad was one of three strategic goals in the German plan, codenamed Operation Barbarossa for the Eastern Front. The strategy was motivated by Leningrad's political status as the former capital of Russia and the symbolic capital of the Russian Revolution, its military importance as a main base of the Soviet Baltic Fleet and its industrial strength, housing numerous arms factories.[9][10] Hitler was so confident of capturing Leningrad that he had the invitations to the victory celebrations to be held in the city's Hotel Astoria already printed.[11] The siege was to be laid by the Army Group North as part of Operation Barbarossa, launched on 21 June 1941 with assistance from the Finnish Defence Forces.[12] The preconditions for the siege were created by the Barbarossa in the south and the Finnish reconquest of the Karelian Isthmus from the north of the city. [edit] Preparations [edit] German plans Army Group North under Field Marshal von Leeb advanced to Leningrad, its primary objective. Von Leeb's plan called for capturing the city on the move, but due to strong resistance from Soviet forces, and also Hitler's recall of 4th Panzer Group, he was forced to besiege the city after reaching the shores of Lake Ladoga, while trying to complete the encirclement and reaching the Finnish Army under Marshal Mannerheim waiting at the Svir River, east of Leningrad.[13] Finnish military forces were located north of Leningrad, while German forces occupied territories to the south.[14] Both German and Finnish forces had the goal of encircling Leningrad and maintaining the blockade perimeter, thus cutting off all communication with the city and restricting them from getting any food or goods.[2][13][15][16][17][18] [edit] Leningrad fortified region On 27 June 1941 the Council of Deputies of the Leningrad administration organized "First response groups" of civilians. In the next days the entire civilian population of Leningrad was informed of the danger and over a million citizens were mobilized for the construction of fortifications. Several lines of defenses were built along the perimeter of the city, in order to repulse hostile forces approaching from north and south by means of civilian resistance.[2][5] One of the fortifications ran from the mouth of the Luga River to Chudovo, Gatchina, Uritsk, Pulkovo and then through the Neva River. The other defense passed through Peterhof to Gatchina, Pulkovo, Kolpino and Koltushy. Another defense line against the Finns, the Karelian Fortified Region, had been maintained in the northern suburbs of Leningrad since the 1930s, and was now returned to service. A total of 190 km of timber barricades, 635 km of wire entanglements, 700 km of anti-tank ditches, 5,000 earth-and-timber emplacements and reinforced concrete weapon emplacements and 25,000 km[citation needed] of open trenches were constructed or excavated by civilians. Even the guns from the Aurora cruiser were moved inland on the Pulkovskiye Heights to the south of Leningrad. [edit] Establishment The 4th Panzer Group from East Prussia took Pskov following a swift advance, and reached the neighborhood of Luga and Novgorod, within operational reach of Leningrad. But it was stopped by fierce resistance south of the city. However, the 18th Army with some 350,000 men lagged behind — forcing its way to Ostrov and Pskov after the Soviet troops of the Northwestern Front retreated towards Leningrad. On 10 July both Ostrov and Pskov were captured and the 18th Army reached Narva and Kingisepp, from where advance toward Leningrad continued from the Luga River line. This had the effect of creating siege positions from the Gulf of Finland to Lake Ladoga, with the eventual aim of isolating Leningrad from all directions. The Finnish Army was then expected to advance along the eastern shore of Lake Ladoga.[19] [edit] Orders of battle Showing Army Group North's advance into USSR in 1941. Coral up to Jul 9. Pink up to Sep 1. Green up to Dec 5. [edit] Germany Army Group North (Field Marshal von Leeb)[20] o 18th Army (von Küchler) XXXXII Corps (2 infantry divisions) XXVI Corps (3 inf divisions) o 16th Army (Busch) XXVIII Corps (2 inf, 1 armored divisions) I Corps (2 inf divisions) X Corps (3 inf divisions) II Corps (3 inf divisions) (L Corps — Under 9. Army) (2 inf divisions) o 4th Panzergruppe (Hoepner) XXXVIII Corps (1 inf division) XXXXI Motorized Corps (Reinhard) (1 inf, 1 motorized, 1 armored divisions) LVI Motorized Corps (von Manstain) (1 inf, 1 mot, 1 arm, 1 panzergrenadier divisions) [edit] Finland Finnish Defence Forces HQ (Marshal of Finland Mannerheim)[21] o I Corps (2 infantry divisions) o II Corps (2 inf divisions) o IV Corps (3 inf divisions) [edit] Soviet Union Northern Front (Lieutenant General Popov)[22] o 7th Army (2 rifle, 1 militia divisions, 1 marine brigade, 3 motorized rifle and 1 armored regiments) o 8th Army X Rifle Corps (2 rifle divisions) XI Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions) Separate Units (3 rifle divisions) o 14th Army XXXXII Rifle Corps (2 rifle divisions) Separate Units (2 rifle divisions, 1 Fortified area, 1 motorized rifle regiment) o 23rd Army XIX Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions) Separate Units (2 rifle, 1 mot divisions, 2 Fortified areas, 1 rifle regiment) o Luga Operation group XXXXI Rifle Corps (3 rifle divisions) Separate Units (1 armored brigade, 1 rifle regiment) o Kingisepp Operation Group Separate Units (2 rifle, 2 militia, 1 armored divisions, 1 Fortified area) o Separate Units (3 rifle divisions, 4 guard militia divisions, 3 Fortified areas, 1 rifle brigade) From these, 14th Army defended Murmansk and 7th Army defended Ladoga Karelia; thus they did not participate in the initial stages of the siege. 8th Army was initially part of the Northwestern Front and retreated through the Baltics. (8th army was transferred to Northern Front on July 14). At 23 August the Northern front was divided to Leningrad front and Karelian front, as it become impossible for front HQ to control everything between Murmansk and Leningrad. [edit] Severing lines of communication On 6 August Hitler repeated his order: "Leningrad first, Donetsk Basin second, Moscow third."[23] From August 1941 to January 1944 anything that happened between the Arctic Ocean and Lake Ilmen concerned the Wehrmacht's Leningrad siege operations.[5] Arctic convoys using the Northern Sea Route delivered American Lend-Lease food and war material supplies to the Murmansk railhead (although the rail link to Leningrad became cut by Finnish armies just north of the city); and also supplies to several other locations in Lapland.[citation needed] [edit] Encirclement of Leningrad Finnish intelligence was particularly helpful for Hitler, as the Finns had broken some of the Soviet military codes and were able to read their low-level correspondence.[24] He constantly requested intelligence information about Leningrad.[5] Finland's role in Operation Barbarossa was laid out in Hitler's Directive 21, "The mass of the Finnish army will have the task, in accordance with the advance made by the northern wing of the German armies, of tying up maximum Russian strength by attacking to the west, or on both sides, of Lake Ladoga".[25] The last rail connection to Leningrad was severed on August 30, when Germans reached the Neva River. On September 8, the last land connection to the besieged city was severed when the Germans reached Lake Ladoga at Orekhovets. Bombing on September 8 caused 178 fires.[26] Hitler's directive on October 7, signed by Alfred Jodl was a reminder not to accept capitulation.[27] [edit] Finland and Germany By August 1941, the Finns had advanced within 20 km of the northern suburbs of Leningrad, threatening the city from the north, and were also advancing through Karelia, east of Lake Ladoga, threatening the city from the east. However, Finnish forces halted their advance several kilometers away from the suburbs of Leningrad at the old Soviet-Finnish border on the Karelian Isthmus.[28] The Finnish headquarters rejected German pleas for aerial attacks against Leningrad[29] and did not advance farther south from the River Svir in the occupied East Karelia (160 kilometers northeast of Leningrad), which they reached on September 7. In the southeast, Germans captured Tikhvin on November 8, but failed to complete the encirclement of Leningrad by advancing further north to join with the Finns at the Svir River. A month later, on December 9 a counter-attack of the Volkhov Front forced the Wehrmacht to retreat from the Tikhvin positions to the River Volkhov line.[2][5] Hitler with Finland's Marshal Carl Gustav Mannerheim and President Risto Ryti; meeting in Imatra, Finland, 200 km north-west of Leningrad, in 1942 On the 6th of September 1941 Mannerheim received the Order Of The Iron Cross for his command in the campaign[citation needed]. Germany's Chief of Staff Jodl brought the award to him with a personal letter from Hitler for the award ceremony held at Helsinki. Mannerheim was later photographed wearing the decoration while meeting Hitler.[30][31] Jodl's main reason for coming to Helsinki was to persuade Mannerheim to continue the Finnish offensive. During 1941 Finnish President Ryti declared in numerous speeches to the Finnish Parliament that the aim of the war was to gain more territories in the east and create a "Greater Finland"[32][33][34] However, after the war he was sentenced to prison for crimes against humanity, then he changed his story and stated: "On August 24, 1941 I visited the headquarters of Marshal Mannerheim. The Germans aimed us at crossing the old border and continuing the offensive to Leningrad. I said that the capture of Leningrad was not our goal and that we should not take part in it. Mannerheim and the military minister Walden agreed with me and refused the offers of the Germans. The result was a paradoxical situation: the Germans could not approach Leningrad from the north..." In fact the German and Finnish armies maintained the siege together until January 1944, but there was little, or no systematic shelling or bombing from the Finnish positions.[14] The proximity of the Finnish army's positions - 33-35 kilometers from the center of Leningrad — and the threat of a Finnish attack complicated the defense of the city. At one point the Front Commander Popov could not release reserves facing the Finnish Army for deployment against the Wehrmacht because they were needed to bolster the 23rd Army's defence on the Karelian Isthmus.[35] On August 31, 1941 Mannerheim ordered a stop to the offensive when the Finnish advance reached the 1939 border at the shores of the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, after which Finnish offensives only continued by way of reducing the salients of Beloostrov and Kirjasalo,[36] which threatened Finnish positions at the coast of the Gulf of Finland and south of river Vuoksi respectively.[36] As the Finns reached the line during the first days of September, Popov experienced a reduction in pressure on Red Army forces, allowing him to transfer two divisions to the German sector on September 5.[37] However, in November 1941, Finnish forces made another advance towards Leningrad and crossed the Sestra River, but were stopped again at the Sestroretsk and Beloostrov settlements 20–25 km north of Leningrad's outer suburbs.[14][38] There is no information in Finnish sources of such an offensive and neither do Finnish casualty reports indicate any excess casualties at the time.[39] On the other hand, Soviet forces captured the so-called "Munakukkula" hill one kilometer west from Lake Lempaala in the evening of November 8, but Finns recaptured it next morning.[40] Later, in the summer of 1942, a special Naval Detachment K was formed from Finnish, German and Italian naval units under Finnish operational command. Its purpose was to patrol the waters of Lake Ladoga, and it became involved in clashes against Leningrad supply route on southern Ladoga[14][24][41] [edit] Defensive operations Initial defence of Leningrad was undertaken by the troops of the Leningrad Front commanded by Marshal Kliment Voroshilov which included the 23rd Army in the northern sector between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga, and the 48th Army (Soviet Union) occupying the western sector between Gulf of Finland and the Slutsk-Mga position. Also in the Front were the Leningrad Fortified Region, the Leningrad garrison, the Baltic Fleet forces, and the Koporsk, Southern and Slutsk-Kolpin operational groups. [edit] Defense of civilian evacuees By September 1941 the link with the Volkhov Front (commanded by Kirill Meretskov) was severed and the defensive sectors were held by four armies: 23rd Army in the northern sector, 42rd Army on the western sector, 55th Army on the southern sector, and the 67th Army on the eastern sector. The 8th Army of the Volkhov Front had the responsibility of maintaining the logistic route to the city in coordination with the Ladoga Flotilla. Air cover for the city was provided by the Leningrad military district PVO Corps and Baltic Fleet naval aviation units. The defense operation to protect the 1,400,000 civilian evacuees was part of the Leningrad counter-siege operations, and was carried under the command of Andrei Zhdanov, Kliment Voroshilov, and Aleksei Kuznetsov. Additional military operations were carried in coordination with the Baltic Fleet naval forces under the general command of Admiral Vladimir Tributs. Major military involvement in helping evacuation of the civilians was carried by the Ladoga Flotilla under the command of V. Baranovsky, S.V. Zemlyanichenko, P.A. Traynin, and B.V. Khoroshikhin. [edit] Bombardment By September 8, 1941 German forces had largely surrounded the city, cutting off all supply routes to Leningrad and its suburbs. Unable to press home their offensive, and facing defenses of the city organized by Marshal Zhukov, the Axis armies laid siege to the city for 872 days. Artillery bombardments of Leningrad began in August 1941, increasing in intensity during 1942 with the arrival of new equipment. It was stepped up further during 1943, when several times as many shells and bombs were used as in the year before. Torpedoes were often used for night bombings by the Luftwaffe.[citation needed] Against this, the Soviet Baltic Fleet Navy aviation made over 100,000 air missions to support their military operations during the siege.[42] German shelling and bombings killed 5,723 and wounded 20,507 civilians in Leningrad during the siege.[43] [edit] Supplying the defenders To sustain the defense of the city it was vitally important for the Red Army to establish a route for bringing constant supplies into Leningrad. This route was effected over the southern part of Lake Ladoga, by means of watercraft during the warmer months and land vehicles driven over thick ice in the winter. The security of the supply route was ensured by the Ladoga Flotilla, the Leningrad PVO Corps, and route security troops. The route would also be used to evacuate civilians from the besieged city. This was because no evacuation plan had been made available in the chaos of the first winter of the war, and the city literally starved in complete isolation until November 20, 1941 when the ice road over Lake Ladoga became operational. This road was named the Road of Life (Russian: Дорога жизни). As a road it was very dangerous. There was the risk of vehicles becoming stuck in the snow or sinking through broken ice caused by the constant German bombardment. Because of the high winter death toll the route also became known as the "Road of Death". However, the lifeline did bring military and food supplies in and took civilians out, allowing the city to continue resisting the enemy. [edit] Effect on the city Main article: Effect of the Siege of Leningrad on the city The two-and-a-half year siege caused the greatest destruction and the largest loss of life ever known in a modern city.[14] On Hitler's express orders, most of the palaces of the Tsars, such as the Catherine Palace, Peterhof Palace, Ropsha, Strelna, Gatchina, and other historic landmarks located outside the city's defensive perimeter were looted and then destroyed, with many art collections transported to Nazi Germany.[44] A number of factories, schools, hospitals and other civil infrastructure were destroyed by air raids and long range artillery bombardment. The diary of Tanya Savicheva, a girl of 11, her notes about starvation and deaths of her grandmother, then uncle, then mother, then brother, the last record saying "Only Tanya is left." She died of progressive dystrophy shortly after the siege. Her diary was shown at the Nuremberg trials. The 872 days of the siege caused unparalleled famine in the Leningrad region through disruption of utilities, water, energy and food supplies. This resulted in the deaths of up to 1,500,000[45] soldiers and civilians and the evacuation of 1,400,000 more, mainly women and children, many of whom died during evacuation due to starvation and bombardment.[1][2][5] Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery alone in Leningrad holds half a million civilian victims of the siege. Economic destruction and human losses in Leningrad on both sides exceeded those of the Battle of Stalingrad, the Battle of Moscow, or the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The siege of Leningrad is the most lethal siege in world history, and some historians speak of the siege operations in terms of genocide, as a "racially motivated starvation policy" that became an integral part of the unprecedented German war of extermination against populations of the Soviet Union generally.[46][47] Civilians in the city suffered from extreme starvation, especially in winter of 1941–1942. For example, from November 1941 to February 1942 the only food available to the citizen was 125 grams of bread, which by 50–60 per cent consisted of sawdust and other inedible admixtures, and distributed with ration cards. For about 2 weeks at the beginning of January 1942 even this food was availible only for workers and military personnel. In conditions of extreme temperatures (down to −30 °С) and city transport being out of service a few kilometers to the food distributing kiosks were insurmountable obstacle for many citizens. In January-February of 1942 about 700–10,000 citizens died every day, most of them from hunger. People often died on the streets, and citizens shortly became accustomed to look of death. Reports of cannibalism appeared in the winter of 1941-1942, after all birds, rats and pets were eaten by survivors.[48] Leningrad police even formed a special unit to combat cannibalism.[49] [edit] Soviet relief of the siege Soviet ski troops by the Hermitage Museum in Leningrad. [edit] Sinyavin Offensive The Sinyavin Offensive was a Soviet attempt of breaking the blockade of the city in early autumn 1942. The 2nd Shock and the 8th armies were to link up with the forces of the Leningrad Front. At the same time the German side was preparing an offensive Operation Nordlicht to capture the city, using the troops freed up after the capture of Sevastopol.[50] Neither side was aware of the other's intentions until the battle started. The Sinyavin offensive started on the 27th August 1942, with some small-scale attacks by the Leningrad front on the 19th, pre-empting "Nordlicht" by a few weeks. The successful start of the operation forced the German to redirect troops from the planned "Nordlicht" to counterattack the Soviet armies. The counteroffensive saw the first deployment of the Tiger tank, though with limited success. After parts of the 2nd strike army were encircled and destroyed, the Soviet offensive was halted. However the German forces had to abandon their offensive on Leningrad as well. [edit] Operation Iskra The encirclement was broken in the wake of Operation Iskra - (English: Operation Spark) - a full-scale offensive conducted by the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts. This offensive started in the morning of January 12, 1943. After fierce battles the Red Army units overcame the powerful German fortifications to the south of Lake Ladoga, and on January 18, 1943 the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts met, opening a 10–12 km wide land corridor, which could provide some relief to the besieged population of Leningrad. [edit] Lifting the siege The siege continued until January 27, 1944, when the Soviet Leningrad-Novgorod Strategic Offensive expelled German forces from the southern outskirts of the city. This was a combined effort by the Leningrad and Volkhov Fronts, along with the 1st and 2nd Baltic Fronts. The Baltic Fleet provided 30% of aviation power for the final strike against the Wehrmacht.[42] In the summer of 1944, the Finnish Defence Forces were pushed back to the other side of the Bay of Vyborg and the Vuoksi River. [edit] Timeline [edit] 1941 April: Hitler intends to occupy and then destroy Leningrad, according to plan Barbarossa and Generalplan Ost[51] June 22: The Axis powers' invasion of Soviet Union begins with Operation Barbarossa. June 23: Leningrad commander M. Popov, sends his second in command to reconnoiter defensive positions south of Leningrad.[52] June 29: Construction of the Luga-line defense fortifications begins[53] together with evacuation of children and women. June–July: Over 300 thousand civilian refugees from Pskov and Novgorod escaping from the advancing Germans come to Leningrad for shelter. The armies of the North-Western Front join the front lines at Leningrad. Total military strength with reserves and volunteers reaches 2 million men involved on all sides of the emerging battle.[citation needed] July 19–23: First attack on Leningrad by Army Group North is stopped 100 km south of the city.[citation needed] July 27: Hitler visits Army Group North, angry at the delay. He orders Field Marshal von Leeb to take Leningrad by December.[51] July 31: Finns attack the Soviet 23rd Army at the Karelian Isthmus, eventually reaching northern pre-Winter War Finnish-Soviet border. August 20 – September 8: Artillery bombardments of Leningrad hit industries, schools, hospitals, and civilian houses. August 21: Hitler's Directive No.34 orders "Encirclement of Leningrad in conjunction with the Finns."[54] August 20 – 27: Evacuation of civilians is blocked by attacks on railroads and other exits from Leningrad.[55] August 31: Finnish forces go on the defensive and straighten their front line.[28] This involves crossing the 1939 pre-Winter War border and occupation of municipalities of Kirjasalo and Beloostrov.[28] September 6: German High Command's Alfred Jodl fails to persuade Finns to continue offensive against Leningrad.[29] September 2 - 9: Finns capture the Beloostrov and Kirjasalo salients and conduct defensive preparations.[36][38] September 8: Land encirclement of Leningrad is completed when the German forces reach the shores of Lake Ladoga.[14][51] September 10: Joseph Stalin appoints General Zhukov to replace Marshal Voroshilov as Leningrad Front commander.[56] September 12: The largest food depot in Leningrad, the Badajevski General Store, is destroyed by a German bomb.[57] September 15: von Leeb has to remove the 4th Panzergruppe from the front lines and transfer it to Army Group Center for the Moscow offensive.[58] September 19: German troops are stopped 10 km from Leningrad. Citizens join the fighting at the defense lines.[citation needed] 1,496,000 Soviet personnel were awarded the medal for the defence of Leningrad from 22nd December 1942. September 22: Hitler directs that "Saint Petersburg must be erased from the face of the Earth".[59] September 22: Hitler declares, "....we have no interest in saving lives of the civilian population."[59] November 8: Hitler states in a speech at Munich: "Leningrad must die of starvation."[14] November 10: Soviet counter-attack begins, forcing Germans to retreat from Tikhvin back to the Volkhov River by December 30, preventing them from joining Finnish forces stationed at the Svir River east of Leningrad.[60] December: Winston Churchill wrote in his diary "Leningrad is encircled, but not taken."[61] December 6 Great Britain declared war on Finland. This was followed by declaration of war from Canada, Australia, India and New Zealand.[62] [edit] 1942 January 7: Soviet Lyuban Offensive is launched; it lasts 16 weeks and is unsuccessful, resulting in the loss of the 2nd Shock Army. January: Soviets launch battle for the Nevsky Pyatachok bridgehead in an attempt to break the siege. This battle lasts until May 1943, but is only partially successful. Very heavy casualties experienced by both sides. April 4 - 30: Luftwaffe operation Eis Stoß (Ice impact) fails to sink Baltic Fleet ships iced in at Leningrad.[63] June–September: New German artillery bombards Leningrad with 800 kg shells. August: The Spanish Blue Division (División Azul) transferred to Leningrad. August 14 – October 27 : Naval Detachment K clashes with Leningrad supply route on Lake Ladoga.[14][24][41] August 19: Soviets begin a 8 week long Sinyavin relief offensive, which fails to lift the siege, but thwarts German offensive plans (Nordlicht).[64] [edit] 1943 January–December: Increased artillery bombardments of Leningrad. January 12 – January 30: Operation Iskra penetrates the siege by opening a land corridor along the coast of Lake Ladoga into the city. [edit] 1944 January 14 - March 1: Several Soviet offensive operations begin, aimed at ending the siege. January 27: Siege of Leningrad ends. Germans forces pushed 60–100 km away from the city. January: Before retreating the German armies loot and destroy the historical Palaces of the Tsars, such as the Catherine Palace, Peterhof Palace, the Gatchina, and the Strelna. Many other historic landmarks and homes in the suburbs of St. Petersburg are looted and then destroyed, and a large number of valuable art collections is moved to Nazi Germany. During the siege, 3200 residential buildings, 9000 wooden houses (burned), 840 factories and plants were destroyed in Leningrad and suburbs.[65] [edit] Additional notes [edit] Controversy over Finnish participation Almost all historians regard the siege as a German operation and do not consider that the Finns effectively participated in the siege.[66] Only Nikolai Baryshnikov has been a strong supporter of the view that active Finnish participation occurred. The main issues which count in favour of the former view are: (a) the Finns stayed at the pre-winter war border at the Karelian Isthmus, despite German wishes and requests, and (b) they did not bombard the city from planes or with artillery and did not allow the Germans to bring their own land forces to Finnish lines. [edit] Monument to the 'Road of Life' On October 29, 1966 a monument to the Road of Life was erected. Entitled 'Broken Ring,' designed and created by Konstantin Simun, this monument pays tribute not only to the lives saved via the frozen Ladoga, but also the many lives broken by the blockade. The monument is a huge bronze ring with a gap in it, pointing towards the site that the Russians eventually broke through the encircling German forces. The German bunker they captured is preserved as a momento opposite the break. In the centre a Russian mother cradles her dying soldier son. It is customary for all newlyweds to come here to give thanks to the fallen. Whilst being sited in the centre of a roundabout it is easily accessed. The monument implies that the siege lasted 900 days. [edit] See also Operation Barbarossa Eastern Front (World War II) Adolf Hitler Mannerheim Tanya Savicheva World War II casualties Naval Detachment K List of famines Blue Division (División Azul) Effect of the Siege of Leningrad on the city Consequences of German Nazism Piskaryovskoye Memorial Cemetery Lake Ladoga Nevsky Pyatachok Leningrad Affair [edit] External links External images the Siege of Leningrad Russian map of the operations around Leningrad in 1943 Blue are the German and co-belligerent Finnish troops. The Soviets are red.[67] map of the advance on Leningrad and relief Blue are the German and allied Finnish troops. The Soviets are red.[68] (Youtube) Leningrad blockade part1 (Retrieved on June 29, 2008) [edit] References Backlund, L.S. (1983), Nazi Germany and Finland, University of Pennsylvania. University Microfilms International A. Bell & Howell Information Company, Ann Arbor, Michigan Baryshnikov, N.I.; Baryshnikov, V.N. (1997), Terijoen hallitus, TPH Baryshnikov, N.I.; Baryshnikov, V.N.; Fedorov, V.G. (1989), Finlandia vo vtoroi mirivoi voine (Finland in the Second World War), Lenizdat, Leningrad Baryshnikov, N.I.; Manninen, Ohto (1997), Sodan aattona, TPH Baryshnikov, V.N. (1997), Neuvostoliiton Suomen suhteiden kehitys sotaa edeltaneella kaudella, TPH Bethel, Nicholas; Alexandria, Virginia (1981), Russia Besieged, Time-Life Books, 4th Printing, Revised Brinkley, Douglas; Haskey, Mickael E. (2004), The World War II. Desk Reference, Grand Central Press Carell, Paul (1963), Unternehmen Barbarossa — Der Marsch nach Russland Carell, Paul (1966), Verbrannte Erde: Schlacht zwischen Wolga und Weichsel (Scorched Earth: The Russian-German War 1943-1944), Verlag Ullstein GmbH, (Schiffer Publishing), ISBN 088740-598-3 Cartier, Raymond (1977), Der Zweite Weltkrieg (The Second World War), R. Piper & CO. Verlag, München, Zürich Churchill, Winston S., Memoires of the Second World War. An abridgment of the six volumes of The Second World War, Houghton Mifflin Company, Boston, ISBN 0-395-59968-7 Clark, Alan (1965), Barbarossa. The Russian-German Conflict 1941-1945, Perennial, ISBN 0688-04268-6 Fugate, Bryan I. (1984), Operation Barbarossa. Strategy and Tactics on the Eastern Front, 1941, Presidio Press, ISBN 0891411976, ISBN 978-0-89141-197-0 Ganzenmüller, Jörg (2005), Das belagerte Leningrad 1941-1944, Ferdinand Schöningh Verlag, Paderborn, ISBN 350672889X Гречанюк, Н. М.; Дмитриев, В. И.; Корниенко, А. И. (1990), Дважды, Краснознаменный Балтийский Флот (Baltic Fleet), Воениздат Higgins, Trumbull (1966), Hitler and Russia, The Macmillan Company Jokipii, Mauno (1987), Jatkosodan synty (Birth of the Continuation War), ISBN 951-1-08799-1 Juutilainen, Antti; Leskinen, Jari (2005), Jatkosodan pikkujättiläinen, Helsinki Kay, Alex J. (2006), Exploitation, Resettlement, Mass Murder. Political and Economic Planning for German Occupation Policy in the Soviet Union, 1940 - 1941, Berghahn Books, New York, Oxford Miller, Donald L. (2006), The story of World War II, Simon $ Schuster, ISBN 0-74322718-2 National Defence College (1994), Jatkosodan historia 1-6, Porvoo, ISBN 951-0-15332-X Seppinen, Ilkka (1983), Suomen ulkomaankaupan ehdot 1939-1940 (Conditions of Finnish foreign trade 1939-1940), ISBN 951-9254-48-X Симонов, Константин (1979), Записи бесед с Г. К. Жуковым 1965–1966, Hrono Suvorov, Victor (2005), I take my words back, Poznao, ISBN 83-7301-900-X Vehviläinen, Olli; McAlister, Gerard (2002), Finland in the Second World War: Between Germany and Russia, Palgrave [edit] Notes 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. 24. 25. 26. 27. 28. 29. 30. 31. ^ a b Brinkley 2004, p. 210 ^ a b c d e Wykes 1972, pp. 9-21 ^ Siege of Leningrad. Encyclopedia Britannica. ^ Baryshnikov 2003; Juutilainen 2005, p. 670; Ekman, P-O: Tysk-italiensk gästspel på Ladoga 1942, Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet 1973 Jan.–Feb., pp. 5–46. ^ a b c d e f Carell 1966, pp. 205-210 ^ Salisbury 1969, p. 331 ^ a b Glantz 2001, pp. 179 ^ The Siege of Leningrad, 1941 - 1944 ^ Carell 1963 ^ By 1939 the city was responsible for 11% of all Soviet industrial output. (Encyclopedia Britannica. Saint Petersburg, Vol 26, p 1044. 15th edition, 1997) ^ Orchestral manoeuvres (part one). From the Observer ^ Carell 1966, pp. 205-240 ^ a b Carell 1966, pp. 205-208 ^ a b c d e f g h Baryshnikov 2003 ^ Higgins 1966 ^ Brinkley 2004, pp. 210 ^ Miller 2006, pp. 67 ^ Willmott 2004 ^ Хомяков, И (2006) (in Russian). История 24-й танковой дивизии ркка. Санкт-Петербург: BODlib. pp. 232 с. http://www.soldat.ru/force/sssr/24td/24td-4.html. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 367 ^ National Defence College 1994, pp. 2:194,256 ^ Glantz 2001, p. 351 ^ Higgins 1966, pp. 151 ^ a b c Juutilainen 2005, pp. 187-9 ^ Führer Directive 21. Operation Barbarossa ^ "St Petersburg - Leningrad in the Second World War" 9th May 2000. Exhibition. The Russian Embassy. London ^ "Nuremberg Trial Proceedings Vol. 8", from the The Avalon Project at Yale Law School ^ a b c National Defence College 1994, p. 2:261 ^ a b National Defence College 1994, p. 2:260 ^ "Hitler–Mannerheim meeting (fragment)". http://www.feldgrau.net/phpBB2/viewtopic.php?p=88528. ^ Mannerheim - Commander-in-Chief from mannerheim.fi 32. ^ Vehviläinen 2002 33. ^ Пыхалов, И (2003). "«великая оболганная война»". Военная литература. Со сслылкой на Барышников В.Н.Вступление Финляндии во Вторую мировую войну. 1940-1941 гг. СПб. Militera. pp. с. 28. http://militera.lib.ru/research/pyhalov_i/11.html. Retrieved 200709-25. 34. ^ "«и вновь продолжается бой...»". Андрей Сомов. Центр Политических и Социальных Исследований Республики Карелия.. Politika-Karelia. http://politikakarelia.ru/shtml/article.shtml?id=16. Retrieved 2007-09-25. 35. ^ Glantz 2001, pp. 33–34 36. ^ a b c National Defence College 1994, pp. 2:262-267 37. ^ Platonov 1964 38. ^ a b "Approaching Leningrad from the North. Finland in WWII (На северных подступах к Ленинграду)" (in Russian). http://www.aroundspb.ru/finnish/saveljev/war1941.php. 39. ^ "Database of Finns killed in WWII". War Archive. Finnish National Archive. http://kronos.narc.fi/menehtyneet/. 40. ^ National Defence College 1994, p. 4:196 41. ^ a b Ekman, P-O: Tysk-italiensk gästspel på Ladoga 1942, Tidskrift i Sjöväsendet 1973 Jan.– Feb., pp. 5–46. 42. ^ a b Гречанюк 1990 43. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 130 44. ^ Nicholas, Lynn H. (1995). The Rape of Europa: the Fate of Europe's Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. Vintage Books 45. ^ Salisbury 1969, pp. 590f 46. ^ Ganzenmüller 2005, pp. 17,20 47. ^ Barber 2005 48. ^ 900-Day Siege of Leningrad 49. ^ This Day in History 1941: Siege of Leningrad begins 50. ^ E. Manstein. Lost victories. Ch 10 51. ^ a b c Cartier 1977 52. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 31 53. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 42 54. ^ Higgins 1966, pp. 156 55. ^ The World War II. Desk Reference. Eisenhower Center director Douglas Brinkley. Editor Mickael E. Haskey. Grand Central Press, 2004. Page 8. 56. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 64 57. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 114 58. ^ Glantz 2001, p. 71 59. ^ a b Hitler, Adolf (1941-09-22). "Directive No. 1601" (in Russian). http://www.hrono.ru/dokum/194_dok/19410922.html. 60. ^ Carell 1966, pp. 210 61. ^ Churchill, Winston (2000) [1950]. The Second World War (The Folio Society ed.). London: Cassel & Co. pp. Volume III, pp.. 62. ^ pp.98-105, Finland in the Second World War, Bergharhn Books, 2006 63. ^ Bernstein, AI; Бернштейн, АИ (1983). "Notes of aviation engineer (Аэростаты над Ленинградом. Записки инженера — воздухоплавателя. Химия и Жизнь №5)" (in Russian). pp. с. 8–16. http://xarhive.narod.ru/Online/hist/anl.html. 64. ^ Glantz 2001, pp. 167-173 65. ^ Siege of 1941-1944 66. ^ Baryshnikov 2003, p. 3 67. ^ "ОТЕЧЕСТВЕННАЯ ИСТОРИЯ. Тема 8". Ido.edu.ru. http://www.ido.edu.ru/ffec/hist/h8.html. Retrieved 2008-10-26. 68. ^ "ИТАР-ТАСС :: 60 ЛЕТ ВЕЛИКОЙ ПОБЕДЕ ::" (in (Russian)). Victory.tass-online.ru. http://victory.tass-online.ru/?page=gallery&gcid=9. Retrieved 2008-10-26. [edit] Bibliography Wikimedia Commons has media related to: Siege of Leningrad Barber, John; Dzeniskevich, Andrei (2005), Life and Death in Besieged Leningrad, 1941–44, Palgrave Macmillan, New York, ISBN 1-4039-0142-2 Baryshnikov, N.I. (2003), Блокада Ленинграда и Финляндия 1941–44 (Finland and the Siege of Leningrad), Институт Йохана Бекмана Glantz, David (2001), The Siege of Leningrad 1941–44: 900 Days of Terror, Zenith Press, Osceola, WI, ISBN 0-7603-0941-8 Goure, Leon (1981), The Siege of Leningrad, Stanford University Press, Palo Alto, CA, ISBN 08047-0115-6 Granin, Daniil Alexandrovich (2007), Leningrad Under Siege, Pen and Sword Books Ltd, ISBN 9781844154586 Kirschenbaum, Lisa (2006), The Legacy of the Siege of Leningrad, 1941–1995: Myth, Memories, and Monuments, Cambridge University Press, New York, ISBN ISBN 0-521-86326-0 Lubbeck, William; Hurt, David B. (2006), At Leningrad's Gates: The Story of a Soldier with Army Group North, Pen and Sword Books Ltd, ISBN 9781844156177 Platonov, S.P. ed. (1964), Bitva za Leningrad, Voenizdat Ministerstva oborony SSSR, Moscow Salisbury, Harrison Evans (1969), The 900 Days: The Siege of Leningrad, Da Capo Press, ISBN 0-306-81298-3 Simmons, Cynthia; Perlina, Nina (2005), Writing the Siege of Leningrad. Women's diaries, Memories, and Documentary Prose, University of Pittsburgh Press, ISBN 9780822958697 Willmott, H.P.; Cross, Robin; Messenger, Charles (2004), The Siege of Leningrad in World War II, Dorling Kindersley, ISBN 978-0-7566-2968-7 Wykes, Alan (1972), The Siege of Leningrad, Ballantines Illustrated History of WWII [show] v•d•e World War II Allies (Leaders) Ethiopia · China · Czechoslovakia · Poland · United Kingdom · India · France · Australia · New Zealand · South Africa · Canada · Norway · Belgium · Netherlands · Egypt · Greece · Yugoslavia · Soviet Union · United States · Philippines · Mexico · Brazil Axis and Axis-aligned Italy · Japan · Germany · Slovakia · Bulgaria · Croatia · Finland · Hungary · Romania · Thailand · Manchukuo · Italian Social Republic · Iraq (Leaders) Resistance Austria · Baltic States · Belgium · Czech lands · Denmark · Estonia · Ethiopia · France · Germany · Greece · Italy · Jewish · Korea · Latvia · Netherlands · Norway · Philippines · Poland · Thailand · Soviet Union · Slovakia · Western Ukraine · Vietnam · Yugoslavia Prelude Africa · Asia · Europe 1939 Invasion of Poland · Phoney War · Winter War · Battle of the Atlantic 1940 Denmark and Norway · Battle of the Netherlands · Battle of Belgium · Battle of France · Battle of Britain · Libya and Egypt · British Somaliland · Baltic states · Bessarabia and Northern Bukovina · Invasion of French Indochina · Invasion of Greece · Operation Compass 1941 East Africa Campaign · Invasion of Yugoslavia · Yugoslav Front · Battle of Greece · Battle of Crete · Invasion of the Soviet Union (Operation Barbarossa) · Continuation War · Middle East Campaign · Battle of Kiev · Siege of Leningrad · Battle of Moscow · Siege of Sevastopol · Attack on Pearl Harbor 1942 Changsha · Battle of the Coral Sea · Battle of Midway · Case Blue · Battle of Stalingrad · Battle of Gazala · Second Battle of El Alamein · Operation Torch · Guadalcanal Campaign 1943 End in Africa · Battle of Kursk · Battle of Smolensk · Solomon Islands · Invasion of Sicily · Lower Dnieper Offensive · Invasion of Italy · Gilbert and Marshall Islands 1944 Cassino and Anzio · Narva · Cherkassy · Operation Tempest · Operation IchiGo · Invasion of Normandy · Mariana and Palau Islands · Operation Bagration · Lvov–Sandomierz Offensive · Warsaw Uprising · Jassy– Kishinev Offensive · Belgrade Offensive · Liberation of Paris · Gothic Line · Operation Market Garden · Operation Crossbow · Operation Pointblank · Lapland War · Budapest Offensive · Battle of Leyte Gulf · Battle of the Bulge · Burma Campaign 1945 Vistula–Oder Offensive · Battle of Iwo Jima · Battle of Okinawa · Final offensive in Italy · Battle of Berlin · Prague Offensive · Siege of Budapest · Surrender of Germany · Soviet invasion of Manchuria · Philippine liberation · Atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki · Surrender of Japan General Attacks on North America · Blitzkrieg · Comparative military ranks · Cryptography · Home front · Military awards · Military equipment · Military production · Nazi plunder · Technology · Total war Aftermath Effects · Expulsion of Germans · Operation Paperclip · Occupation of Germany · Morgenthau Plan · Territorial changes · Soviet occupations: Romania, Poland, Hungary, Baltic States · Occupation of Japan · First Indochina War · Cold War · Decolonization · Contemporary culture War crimes Allied war crimes · German war crimes · Italian war crimes · Japanese war crimes · Soviet war crimes · United States war crimes · The Holocaust · Bombing of civilians · Bengal famine of 1943 War rape Rape during the occupation of Japan · Comfort women · Rape of Nanking · Mass rape of German women by Soviet Red Army Prisoners Italian prisoners of war in the Soviet Union · Japanese prisoners of war in the Soviet Union · Japanese prisoners of war in World War II · German prisoners of war in the Soviet Union Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Siege_of_Leningrad" Categories: World War II aerial operations and battles of the Eastern Front | Strategic operations of the Red Army in World War II | Sieges involving Germany | Sieges involving the Soviet Union | History of Saint Petersburg | Conflicts in 1941 | Baltic operations of World War II | Battles and operations of World War II involving Germany | Cannibalism