Hochgeladen von

rh2rh

Rhetorik und Musik: Die historische Verbindung zwischen Sprache und Musik

Werbung

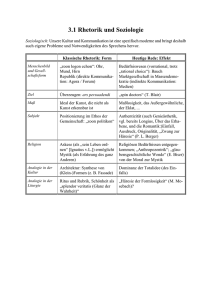

Analog zur seit der Antike tradierten Rhetorik, die den bestmöglichen Einsatz sprachlicher Mittel bei der Gestaltung einer Rede lehrt(e), sah die musikalische Rhetorik seit dem 14. Jh. „Zweck und Absicht“ darin, „die gehörige und beste Anwendung der Ton- oder Ideensprache“ zu garantieren. Dieses Verdikt, von J. N. Forkel noch 1788 formuliert, basiert auf der Ansicht, dass die Musik selbst eine „Sprache“ sei und als solche sowohl den Gesetzen der Rhetorik zu gehorchen als auch „Inhaltliches“ zu vermitteln habe. Und ebenso analog sah man wie der sprachlichen auch der musikalischen Rhetorik eine Grammatik vorgelagert: Diese lehrte „die Zusammensetzung einzelner Gedanken aus Tönen und Accorden, von ihrer ersten Bildung und Biegung an, bis zur allmähligen Zusammensetzung erst einzelner, dann mehrerer musikalischen Wörter zu einem Satze“. Bekanntlich hatte bereits die Notation von Musik ihren Ausgang bei Rhetorik und Prosodie genommen, und die hochmittelalterliche Modalrhythmik fußte auf einer Versmaß-adäquaten Übertragung von Längen und Kürzen der Silben. Im weiteren Verlauf der Musikgeschichte verfestigte sich das allgemeine Bewusstsein von einer tiefgehenden Verwandtschaft von Musik und Rhetorik noch mehr, und diese Verwandtschaft drückte sich auf drei Ebenen aus. Zunächst einmal wurden „rhetorische“ Mittel zur Textaussage, zur Verdeutlichung des „Inhalts“, herangezogen, und hier konnten ganz bewusst auch „Fehler“ eingesetzt werden. So verglich Marchettus von Padua bereits 1325 die „colores ad pulchritudinem consonantiarum“ in der Musik mit den „colores rhetorici ad pulchritudinem sententiarum“ in der Grammatik: Die Farbwirkungen der Klänge glichen seiner Meinung nach den rhetorischen Mitteln, die den Schönheiten der Sprache gewidmet seien; und um (in Vokalmusik) den jeweiligen Textausdruck adäquat zu erreichen, dürften sie sich sogar „falscher“ Wendungen bedienen. Um 1380 forderte dann Heinrich Eger von Kalkar: „Ornatus habet musica proprios sicut rhetorica“ – die Musik besitzt wie die Rhetorik ganz spezifische Mittel für den „Schmuck“ (der „musikalischen Rede“). 1477 schließlich wendete Johannes Tinctoris für solche Lizenzen in Anlehnung an die Rhetorik-Lehrbücher des Marcus Fabius Quintilianus den Begriff figura an, und Joachim Burmeister legte um 1600 eine Übersicht über die melodischen und harmonischen „Figuren“ vor. In seinem Gefolge entstanden dann bis weit ins 18. Jh. hinein, ja partiell noch im frühen 19. Jh., zahlreiche Lehrbücher, die die (über 100) „musikalisch-rhetorischen“ Figuren erklären, systematisieren und inhaltlich entschlüsseln, und allgemein herrschte die Meinung vor, man könne ein Musikwerk gar nicht verstehen, geschweige denn vernünftig interpretieren, wenn man nicht seine in allgemeinen Symbolen (Tonsymbolik) und speziellen Figuren verborgene „gantze Meinung“ kenne. Noch 1817 zählte der Prager Kantor J. J. Ryba 31 Figuren auf, darunter (neben melodischen und rhythmischen Symbolen) bildhafte „Malereien“ als Weiterentwicklung der „Mimesis“-Ästhetik sowie akustische Nachahmungen. Und der in Wien wirkende Beethoven-Freund F. A. Kanne bediente sich 1821 weitgehend des Vokabulars der rhetorischen Figuren, um „Inhalt“ und Affektgehalt von W. A. Mozarts Klaviersonaten darzulegen. Insgesamt spiegelt sich hier eine Mehrpoligkeit der Figurenlehre wider, die Kanne als„obund subjektive Vermischung“ sah und in der „alte“ Nachahmungsästhetik und „neue“ Gefühlsästhetik einen umfangreichen Fundus von text- und inhaltsausdeutenden Mitteln bilden. Die zweite Ebene, auf der sich die Sinneinheit von Rhetorik und Musik konstituierte, war die „sprachlichgrammatikalische“. Sie prägte sich in Formen wie dem Rezitativ aus, sie schlug sich in einer „musikalischen Deklamation“ nieder, die taktfrei oder doch zumindest nicht sklavisch nach dem Takt zu erfolgen hatte, sie führte aber auch zu jenem kleingliedrigen „sprechenden“ Artikulieren, durch welches sich das Interpretieren von älterer Musik von dem üblichen spätromantischen „Dauer-Legato“ unterscheiden muss. Noch für L. v. Beethoven bezeichnete sein erster Biograph A. Schindler „das rhetorische Prinzip“ als „Grundwesen aller seiner Musik“ und deren deklamatorische Ausführung als die allein richtige und mögliche. Die dritte Ebene der Verwandtschaft zwischen Rhetorik und Musik ist die großformale. Johann Mattheson etwa meinte 1739, dass Kompositionen wie eine Rede aus „Eingang, Bericht, Antrag, Bekräfftigung, Widerlegung und Schluß“ bestünden, Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart sah die Sonate 1784 als „musikalische Conversation, oder Nachäffung des Menschengesprächs“, H. C. Koch das Konzert 1802 als „leidenschaftliche Unterhaltung des Concertspielers mit dem ihn begleitenden Orchester" und A. Reicha noch 1824 die Sonatenhauptsatzform als zweiteiliges Drama über ein „Thema“ im inhaltlichen Sinne: der 1. Teil sei die „Exposition der Vorgeschichte“, der 2. Teil die „Schürzung des Knotens" (die „Intrige“) sowie seine „Auflösung“. Die Lehre, wie eine Rede (und somit auch eine „Klangrede“) zu verfassen (bzw. auszuarbeiten) ist, umfasste auch in der Musik die Arbeitsstufen Inventio, Dispositio, Elocutio (Elaboratio), (eventuell) Memoria sowie Executio (bzw. Actio oder Pronuntiatio). Die Inventio lehrte das „Finden“ von Gedanken (aus dem „Vorratsmagazin“ der „Topik“) durch Analogieschlüsse, Assoziationen, konnotativ verbundene Affektfelder oder auch durch speziell erfundene Zuordnungen. Die Dispositio war die Gliederung der Werke und geschah ebenfalls analog zur sprachlichen Rh., wie dies oben bei Mattheson oder Reicha zu sehen war. Die Elocutio (Elaboratio) ging dann mit Hilfe aller kompositionstechnischen und variativen Mittel vor sich und war zunächst für den Schmuck (ornatus) der „musikalischen Rede“ verantwortlich, hatte aber in erster Linie durch Symbole und „Figuren“ für „Inhalt“ und „Bedeutung“ der Musik zu sorgen. Zweck der Musik war dabei – wie Page 1 of 3 bei der Rede – sowohl movere als auch docere sowie delectare, also zu „bewegen“, zu „lehren“ und zu „erfreuen“. Der Elocutio folgten schließlich die Memoria, das Lernen, vornehmlich aber das Auswendiglernen, sowie die Executio (Pronuntiatio), die Ausführung (das „sprechende Vortragen“) der Rede bzw. der Musik. Und diese Ausführung hatte nun sowohl selbst den rhetorischen Gesetzen zu gehorchen, erforderte also eine „sprechende“ Artikulation, wie sie auch den von Symbolen und Figuren vermittelten Inhalt weitergeben musste, um den Hörer wirklich zu erreichen, zu „affizieren“. Hartmut Krones, Art. „Rhetorik und Musik‟, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, Zugriff: 27.4.2020(https://www.musiklexikon.ac.at/ml/musik_R/Rhetorik_und_Musik.xml). Analogous to the rhetoric handed down since antiquity, which teaches the best possible use of linguistic means in the composition of a speech, musical rhetoric since the 14th century has seen "purpose and intention" in guaranteeing "the proper and best use of the language of sounds or ideas". This verdict, formulated by J. N. Forkel as late as 1788, is based on the view that music itself is a "language" and as such must both obey the laws of rhetoric and convey "content". And a grammar was seen to precede linguistic rhetoric as well as musical rhetoric: this taught "the composition of individual thoughts from sounds and chords, from their initial formation and bending, to the gradual composition of first individual, then several musical words into a sentence". As is well known, the notation of music had already begun with rhetoric and prosody, and the modal rhythm of the High Middle Ages was based on a transfer of syllable lengths and shortening that was adequate to the verse. In the further course of music history, the general awareness of a deep relationship between music and rhetoric became even more firmly established, and this relationship was expressed on three levels. First of all, "rhetorical" means were used to express the text, to clarify the "content", and here "mistakes" could also be used quite deliberately. As early as 1325, Marchettus of Padua compared the "colores ad pulchritudinem consonantiarum" in music with the "colores rhetorici ad pulchritudinem sententiarum" in grammar: in his opinion, the color effects of the sounds resembled the rhetorical means dedicated to the beauties of language; and in order to adequately achieve (in vocal music) the respective text expression, they could even use "wrong" turns. Around 1380, Heinrich Eger then demanded of Kalkar: "Ornatus habet musica proprios sicut rhetorica" - music, like rhetoric, possesses very specific means for "adornment" (of "musical speech"). Finally, in 1477 Johannes Tinctoris used the term figura for such licenses, following the rhetoric textbooks of Marcus Fabius Quintilianus, and Joachim Burmeister presented a survey of the melodic and harmonic "figures" around 1600. In his wake, numerous textbooks were written well into the 18th century, and in some cases even in the early 19th century, which explain, systematize and decode the (more than 100) "musicalrhetorical" figures, and in general the opinion prevailed that one could not understand a musical work, let alone interpret it sensibly, if one did not know his "whole opinion" hidden in general symbols (tone symbolism) and special fi-gures. As late as 1817 the Prague cantor J. J. Ryba listed 31 figures, among them (besides melodic and rhythmic symbols) pictorial "paintings" as a further development of the "mimesis" aesthetic as well as acoustic imitations. And in 1821, the Beethoven friend F. A. Kanne, who was active in Vienna, made extensive use of the vocabulary of rhetorical figures to describe the "content" and emotional content of W. A. Mozart's piano sonatas. All in all, this reflects a multipolarity in the theory of figures, which Kanne saw as an "ob- and subjective mixture" and in which "old" imitative aesthetics and "new" emotional aesthetics form an extensive pool of means of interpreting text and content. The second level on which the sensory unit of rhetoric and music was constituted was the "linguistic-grammatical" one. It was expressed in forms such as the recitative, it was reflected in a "musical declamation" that had to be performed without time signature or at least not slavishly to the beat, but it also led to that smallminded "speaking" articulation by which the interpretation of older music must differ from the usual late Romantic "permanent legato". Still for L. v. Beethoven, his first biographer A. Schindler described "the rhetorical principle" as the "basic essence of all his music" and its declamatory execution as the only correct and possible one. The third level of the relationship between rhetoric and music is the large-format one. Johann Matthe-son, for example, said in 1739 that compositions like a speech consisted of "entrance, report, request, affirmation, refutation and conclusion", Christian Friedrich Daniel Schubart saw the sonata in 1784 as a "musical conversation, or imitation of the conversation between people", H. C. Koch saw the 1802 concerto as "passionate entertainment of the concert player with the orchestra accompanying him" and A. Reicha still saw the sonata Page 2 of 3 form in 1824 as a two-part drama about a "theme" in the sense of content: the first part was the "exposition of prehistory", the second part the "shortening of the knot" (the "intrigue") and its "dissolution". The teaching of how to compose (or elaborate) a speech (and thus also a "sound speech") also encompassed in music the working stages Inventio, Dispositio, Elocutio (Elabora-tio), (possibly) Memoria as well as Executio (or Actio or Pronuntiatio). Inventio taught the "finding" of thoughts (from the "stock magazine" of "Topik") by means of analogies, associations, connotatively connected fields of affect or also by specially invented assignments. The Dispositio was the structure of the works and was also analogous to the linguistic Rh. as seen above in Mattheson or Reicha. Elocutio (Elaboratio) then proceeded with the help of all compositional and variable means and was initially responsible for the ornamentation (ornatus) of the "musical speech", but had to provide for the "content" and "interpretation" of the music primarily through symbols and "figures". The purpose of the music was - as with the speech - to "move", to "teach" and to "delight", both movere and docere as well as delectare. The elocutio was followed by the memoria, the learning, but primarily the memorization, as well as the execution (pronuntiatio), the execution (the "speaking recitation") of the speech or music. And this execution itself had to obey the rhetorical laws, and thus required a "speaking" articulation, just as it had to pass on the content conveyed by symbols and figures in order to really reach the listener, to "affect" him. Hartmut Krones, Art. „Rhetorik und Musik‟, in: Oesterreichisches Musiklexikon online, Zugriff: 27.4.2020(https://www.musiklexikon.ac.at/ml/musik_R/Rhetorik_und_Musik.xml). Page 3 of 3