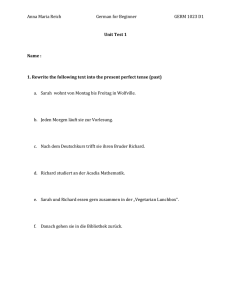

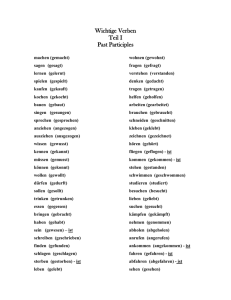

German Level 1 Study Guide

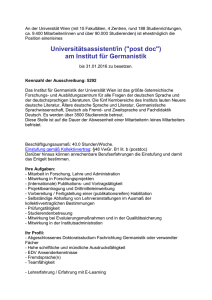

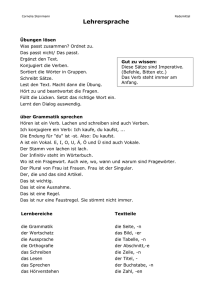

Werbung