KEIN - WORDS + DER - Foreign Affairs Home Page

Werbung

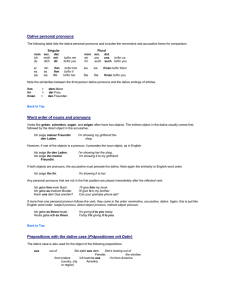

Grammar begrüßen_____________________________________ There are many different ways to greet people, here are the standard forms: Guten Morgen Guten Tag Guten Abend good morning good day good evening Grüß Gott is used often in southern Germany and Austria instead of Guten Morgen / Guten Tag / Guten Abend Grüß dich hi Hallo and even Hi are used frequently by young people . Here are some greetings and possible replies: Guten Morgen, wie geht es Ihnen, Herr Müller? Guten Tag, wie geht’s dir, Peter? Guten Abend, wie geht es Ihnen, Frau Scherer? Grüß dich, Claudia. Wie geht’s dir so? Hallo Bennie, wie geht’s? Danke, gut. Und Ihnen? Nicht schlecht. Und dir? Gut, danke. Und wie geht es Ihnen? Ach, mir geht’s nicht so gut. Oh du, mir geht’s schlecht. “Gute Nacht” is, of course, not a greeting but is used the same way as “Good Night” sich vorstellen___to introduce oneself_________ To introduce yourself you have several options: Guten Tag, mein Name ist Krüger, Udo Krüger. Hallo, ich heiße Jutta, Jutta Scheurig. Tag, ich bin (der) Olaf / (die) Conny and to ask for someone’s name you can use the following: Wie heißen Sie? Wer sind Sie? Wie ist Ihr Name? verabschieden Wie heißt du? Wer bist du? Wie ist dein Name? Wie heißt ihr? Wer seid ihr? < “Auf Wiedersehen” and “Tschüs” are the most common forms used for “Good Bye”. Auf Wiedersehen, Herr Keller. Tschüs Peter, bis morgen. Mach’s gut! Auf Wiedersehen, Frau Kaufmann. Tschüs Angelika, bis später. Macht’s gut! SIE Form - DU / IHR Form_____________________< Like French, German uses two forms of address: familiar and formal. The formal form of address - using the pronoun "Sie" or “Ihnen”- is used with persons one does not know well. The use of the formal form does not indicate coldness or unfriendliness, but respect. These forms are always capitalized. They are usually preceded by an introductory: “Herr” (Mr.) or “Frau” (Mrs/Ms/Miss).Sie / Ihnen use with Herr / Frau and last name Wo wohnen Sie, Herr Krause? (Where do you live, Mr. Krause?) Wie geht es Ihnen, Frau Meyer? (How are you, Mrs. Meyer?) The familiar form of address - using the pronouns "du", “dich” or “dir” for one person or "ihr" , “euch” for several people - is reserved for those people one knows very well, such as family, friends, and children. It is also used more frequently among young people, and within certain groups in society. du / ihr use with first name Wo wohnst du, Till? (Where do you live, Till?) Wie geht es dir, Till? (How are you, Till?) -----Hallo Ben, Nadja, was macht ihr heute abend? (Hi Ben, Nadja, what are you going to do tonight?) Hallo Ben, Nadja, wie geht’s euch so? (Hi Ben, Nadja, how are you? 2 Personal Pronouns______________________________< Personal pronouns are pronouns used to indicate or refer to the: - person(s) speaking 1st person (I / we) - person(s) spoken to 2nd person (you) - person(s) spoken about 3rd person (he, she, it / they) The personal pronouns in German referring to one person (singular form) are: 1st. person ich (I) 2nd person du (familiar form) Sie (formal form) (you) (you) 3rd. person masculine: er feminine: sie neuter: es (he) (she) (it) 3 GRAMMAR Article Words_________________________________________ Since the gender is not usually apparent in the noun itself it is expressed through other parts of speech such as pronouns, adjectives and articles. We deal with articles first. There are two types of articles 1. definite articles (the) 2. indefinite articles (a,an) In German the definite article has three forms in the singular: DER DIE DAS - for all masculine nouns for all feminine nouns for all neuter nouns (der Mantel) (die Bluse) (das Hemd) The indefinite article has only two forms EIN - for all masculine AND neuter nouns EINE - for all feminine nouns (ein Mantel - ein Hemd) (eine Bluse) Nouns_________________________________________ _ In German it is very easy to recognize nouns: they are all capitalized. Nouns are also classified in three grammatical genders: masculine feminine neuter DER DIE DAS Mantel Pullover Schuh Bluse Hose Jacke Hemd Kleid T-Shirt Unfortunately there is no particular rhyme or reason why a noun has its specific gender. That’s why you have to memorize the gender when you learn new nouns. 4 There is some help in predicting the gender of a noun - see list further down. Plural Forms of Nouns____________________________ Nouns also have a singular and a plural form. In English - with a few exceptions - you just add an -s to the singular form. In German there are several possibilities to form the plural: add add add add add add add add add (no change) Umlaut “ e Umlaut “e er Umlaut “er n en s se change um to en der Winter der Vater der Film der Sohn das Kind das Haus die Schwester die Uhr das Radio der Bus die Winter die Väter die Filme die Söhne die Kinder die Häuser die Schwestern die Uhren die Radios die Busse das Museum die Museen Again there is no particular rule and you’ll have to memorize the plural together with the meaning and the gender of each noun. Note: definite article for plurals As you can see from the list of plurals the definite article for plurals is always “DIE” no matter what the gender of the noun was in the singular. indefinite article. There is NO indefinite article for plurals. Here are some rules that can help you predict the gender of a noun: 5 Nouns Gender Indicators__________________________ MASCULINE FEMININE - all nouns referring to males, their professions and nationalities: - nouns referring to females (except: Mädchen), their professions, and nationalities: der Mann der Professor der Kanadier die Frau die Professorin die Kanadierin they often end in: NEUTER - nouns referring to young living beings: das Baby das Kind das Kalb - nouns with diminutive suffixes: - also nouns ending in: -er -ist der Musiker der Pianist Names of all seasons, months, days of the week parts of the day (EXCEPT: die Nacht) geographical directions der Westen der Norden weather phenomena der Wind der Regen -ei die Türkei -enz die Intelligenz -ette die Kassette -ie die Industrie -ik die Musik -ion die Situation -heit die Gesundheit -keit die Möglichkeit -schaft die Mannschaft -tät die Universität -ung die Prüfung -ur die Natur -lein and -chen das Mädchen das Brötchen das Tischlein Nouns ending in -um das Album das Museum das Zentrum and - ment das Regiment das Dokument das Element most nouns that end in: -or der Motor -ismus der Sozialismus NOTE: German has many compound nouns - nouns created by putting two or more nouns together to form a new word. 6 die Stadt die Natur das Jahr der Mittag der Sommer + + + + + das Zentrum = das Museum = die Zeit = das Essen = der Tag = das Stadtzentrum das Naturmuseum die Jahreszeit das Mittagessen der Sommertag (city centre) (nature museum) (season) (lunch) (summer day) Can you figure out the rule from these examples? What is the gender of a compound noun if the individual nouns have different genders? Pronouns______________________________________ _ Pronouns are “stand-ins” for nouns. Since there are three genders there are three different pronouns in the singular: All masculine nouns are represented by ER All feminine nouns are represented by SIE Die Familie ist groß. Der Pullover ist warm. Er ist warm. Sie ist groß. All neuter nouns are represented by ES All plural nouns are represented by SIE Die Eltern sind zu Hause. Das Haus ist neu. Es ist neu. Sie sind zu Hause. Adjective + Comparative___________________________ Adjectives indicate characteristics or qualities. The basic form of the adjective is called “positive” : Mein Bruder ist klein. Der Mann ist groß. Der Film ist lang. To indicate that a person or object has more of a certain quality than another, the comparative form of the adjective is used: Mein Bruder ist kleiner als ich. Der Mann ist größer als mein Vater Der Film ist länger als zwei Stunden. 7 The comparative in German is always formed by adding -er to the adjective, even in the case of long ones like “intelligent”: Mein Hund ist intelligenter als meine Katze. Most one-syllable adjectives with vowels that can carry an Umlaut do so in the comparative. Some adjectives never or rarely have a comparative form, the colours for instance. Some adjectives have irregular forms: Das Mittagessen war gut. Der Wein war besser. To compare things of different value the adjective in the comparative form is followed by the word “als” . It has the same function as the English “than” after a comparative. Mein Bruder ist kleiner als ich. Der Mann ist größer als mein Vater Der Film ist länger als zwei Stunden. To compare two things of equal value you use the adjective in the positive form preceeded by the word “so” and followed by the word “wie”. They fulfill the same function as the English “as ... as”. Meine Schwester ist so groß wie mein Bruder. Mein Onkel ist so alt wie meine Mutter. Zeit (time)__________________________________________________ To find out what time it is now, you can use the following questions: Entschuldigen Sie, bitte ! (Excuse me, please) Wie viel Uhr ist es? Wie spät ist es ? In Germany the official time works on the 24 hour system, informally one uses 12 hours. And these are possible answers: 8 Es ist acht (Uhr). Es ist 8.00Uhr (20.00 Uhr). Es ist zehn nach neun. Es ist 9.10 Uhr (21.10 Uhr). Es ist sieben vor zwölf. Es ist 11.53 Uhr (23.53 Uhr). Es ist Viertel nach fünf. Es ist 5.15 Uhr (17.15Uhr). Es ist Viertel vor zehn. Es ist 9.45 Uhr (21.45 Uhr). Es ist halb drei. Es ist 2.30 Uhr (14.30 Uhr) To find out at what time something begins, ends etc. you can ask: Um wie viel Uhr beginnt das Konzert / der Film? Um wie viel Uhr ist das Konzert / der Film zu Ende? Wann beginnt das Konzert / der Film? Wann ist das Konzert / der Film zu Ende? Das Konzert beginnt um acht Uhr. Das Konzert beginnt um 20.00 Uhr. Der Film ist um halb elf zu Ende. Der Film ist um 22.30 Uhr zu Ende. To find out on what day something happens you can ask: Wann kommt Großmutter / Tante Erna? Großmutter kommt am Donnerstag um 10.30Uhr. Tante Erna kommt auch am Donnerstag aber um Viertel nach elf. To find out what time of the year something happens you again ask: Wann beginnt die Universität / der Frühling? Die Uni beginnt im September. Der Frühling beginnt im März. Here are some rules to remember: to express an exact time (at) to express (in the + time of day) to express (on + day of the week) to express (in the + month or season) 9 use use use use UM: AM: AM: IM : um neun Uhr am Abend am Dienstag im Sommer To find out the duration of an event , you can use the following question: Wie lange dauert das Konzert / der Film ? Das Konzert dauert zwei Stunden und zehn Minuten. Der Film dauert von sieben (Uhr ) bis acht Uhr dreißig. Was machst du im Sommer? Im Juli gehe ich nach Europa. Am 10. Juli fliege ich nach Frankfurt. Der Abflug ist am Abend um elf Uhr in Halifax. Der Flug dauert sechs Stunden und die Maschine landet am nächsten Morgen um zehn in Frankfurt. Und was machst du? Am Freitag fahre ich mit meinem Bruder nach Westen. Am Sonntag sind wir in Montreal und am Dienstag in Toronto. Am Abend ist dort ein Baseballspiel. Es beginnt um sieben Uhr. Im Juli sind wir dann in den Rocky Mountains und wandern dort eine Woche. Im August kommen wir wieder zurück. 10 Personal Pronouns < Personal pronouns are used to indicate or refer to the: person speaking 1st person singular ( I ) persons speaking: 1st person plural ( we ) person spoken to: 2nd person singular ( you ) persons spoken to: 2nd person plural ( you ) person spoken about: 3rd person singular (he / she /it) persons spoken about: 3rd person plural (they ) The personal pronouns in German are: Singular Plural 1st person: 2nd person familiar formal: Sie rd 3 person masculine: feminine: neuter: NOTE: 1. 2. 3. 4. ich du wir ihr Sie er sie es sie for all genders The pronoun "sie" carries four meanings: she they you (singular) you (plural) Heute ist sie hier. Sind Jan und Anne zu Hause? Nein, sie sind nicht hier. Herr Weiß, wie alt sind Sie? Woher sind Sie? Wir sind aus Kanada. Conjugation of SEIN (to be) A verb conjugation is a list of six possible forms of a verb for a particular tense. Each form corresponds to one of the six “persons” from the personal pronouns list. In English regular verb forms change very little. German verbs show greater differences when conjugated, but they are quite predictable. One verb that is irregular in both German and English is the verb “sein” or “to be”. (Sein / to be is the base form of the verb. This form is called: infinitive. It’s the form you’ll find if you look up the verb in a dictionary.) 11 < Here is the conjugation of “sein” for the present and the past tense: present tense singular simple past tense plural singular plural 1. ich bin wir sind 1. ich war wir waren 2. du bist ihr seid 2. du warst ihr wart (formal) 3. er sie ist es Sie sind (formal) Sie waren sie sind 3. er sie war es sie waren Nationalitäten < Länder Nationalitäten Adjektive (das Land) (die Nationalität) (not capitalized) der Amerikaner/der Engländer/der Franzose/n* der Deutsche/n* der Kanadier/der Mexikaner/der Österreicher/der Spanier/der Italiener der Schweizer/- amerikanisch englisch französisch deutsch kanadisch mexikanisch österreichisch spanisch italienisch schweizer(isch) America Great Britain France Germany Canada Mexico Austria Spain Italy Switzerland U.S. Amerika England Frankreich Deutschland Kanada Mexiko Österreich Spanien Italien die Schweiz die USA Countries have a gender - most of them are neuter - but the article is only used if the name is connected with an adjective. However, Switzerland is one of the few exceptions. It is feminine: "die Schweiz" and the name is always used with its article. Das ist Deutschland, und das ist die Schweiz. Ich fahre in die USA. NOTE: The words for many nationalities usually end in -er and the nouns do not change to form a plural. However, there are exceptions. The word for German, for example, is an adjective; one says: der Deutsche (masculine) die Deutsche (feminine) die Deutschen (plural) but without the article it is: Ich bin Deutscher (masculine) Ich bin Deutsche (feminine) 12 Wir sind Deutsche (plural) Berufe < der Arzt/"e der Lehrer/- physician teacher der Professor/-en der Sekretär/e professor secretary German nouns are of three genders, the genders being indicated with the help of articles. Contrary to English, however, nouns indicating nationalities and professions do not use any article if they are connected with a form of the verb to be: Michael ist Lehrer. Er ist Kanadier. Michael is a teacher. He is a Canadian. The Feminine Forms < "Engländer", "Lehrer", and other nouns denoting nationalities and professions refer to a male person; the noun denoting the female counterpart is formed by adding "-in" to the masculine form. At the same time the gender changes from masculine to feminine: der Engländer der Lehrer der Franzose die Engländerin die Lehrerin die Französin (The Umlaut is an exception) Unless the masculine version of the nouns does not end in "-er", the plural form is the same as the singular. The feminine plural is formed by adding "-nen" to the singular: der Kanadier die Kanadierin der Mechaniker die Mechanikerin die Kanadier die Kanadierinnen die Mechaniker die Mechanikerinnen The indefinite article < "Ein" and "eine" are the indefinite articles in German. They correspond to the English "a" or "an". masc. sg.: fem. sg.: neuter sg.: ein ein Tisch (der Tisch - table) eine ein eine Tasche ein Buch (die Tasche - bag) (das Buch - book) 13 The indefinite articles for masculine and neuter nouns are the same. They lack the distinctive endings "r" and "s" respectively. Negation of the indefinite article The negation of the indefinite article is "kein". It is the equivalent of "no", "not a", "not any". It negates nouns. Thus sentences like: I have no answer. This is not a bad idea. I do not need any money. Ich habe keine Antwort. Das ist keine schlechte Idee. Ich brauche kein Geld. use only the negation "kein" in German. Do not confuse "kein" with "nicht", which means strictly "not" and is used to negate sentences, phrases, verbs and adverbs, but not nouns. Das ist nicht weiß. BUT: Das ist kein guter Computer. (This is not white) (This is not a good computer) The word "kein" is treated exactly as "ein". Thus the rules above for "ein" apply likewise to "kein". In fact, for practical reasons, "ein" and "kein" are grouped together and can be referred to as KEIN-WORDS. Unlike "ein", the indefinite article "kein" is able to form a plural: keine (the same last letter as with the plural of the definite article) Nein, das sind keine Kanadier. Nein, das sind keine Professorinnen. Nein, das sind keine Radios. Possessives < Possessives are a group of words that show possession: Singular Plural 1. mein (my) unser (our) 2. dein (your) euer (your) Ihr 3. sein ihr sein (formal) Ihr (his) (her) (its) ihr 14 (formal) (their) The possessives are "KEIN-WORDS", they get the same endings as "kein": Masculine (ich) mein Onkel (du) dein Onkel (er,es) sein Onkel (sie) ihr Onkel Feminine meine Tante deine Tante seine Tante ihre Tante Neuter mein Buch dein Buch sein Buch ihr Buch Plural meine Tische deine Taschen seine Taschen ihre Bücher (wir) unser Onkel (ihr) euer Onkel (sie) ihr Onkel unsere Tante eure Tante ihre Tante unser Buch euer Buch ihr Buch unsere Tische eure Bücher ihre Taschen Ihre Ihr Ihre and formal: (Sie) Ihr Onkel Tante Buch Bücher NOTE: The possessive itself points to the "possessor"; the ending of the possessive is determined by the following noun: Seine Tante ist dort drüben. His aunt is over there. "Sein" points to the owner. The "-e" ending on "sein" is determined by the gender of the noun "Tante". If a possessive is replaced by a pronoun, the regular personal pronouns are used to replace them: Wo ist mein Computer? Er war hier. Das ist meine Uhr. Sie ist neu. Hier ist dein Buch. Es ist interessant. KEIN - WORDS + DER - WORDS Kein - Words ein eine kein keine mein meine dein deine sein seine ihr ihre unser unsere euer a Der - Words der die das die welcher welche welches welche dieser diese dieses diese jeder jede jedes (+ masc / neut) (+ fem) not a (+ masc/ neut) (+ fem) my (+ masc / neut) (+ fem) your (+ masc / neut) (+ fem) his (+ masc / neut) (+ fem) her (+ masc / neut) (+ fem) our (+ masc / neut) (+ fem) < your (+ masc / neut) 15 the (masc) (fem) (neut) (plural) which (masc) (fem) (neut) (plural this (masc) (fem) (neut) (plural) each every (masc) (fem) (neut) eure ihr ihre Ihr + Ihre (+ fem) their (+ masc / neut) alle (+ fem) you formal 16 all Adjectives and their endings < I. Adjectives preceded by a DER-WORD der die dieses welche gute warme kalte guten Wein Milch Bier Studenten ? If an adjective is preceded by a DER-WORD, the ending is "e" before a noun in singular, "en" before a plural noun. II. Adjectives preceded by a KEIN-WORD Since the indefinite articles for masculine and neuter nouns do not show the characteristic endings for masc. and neut., an adjective placed between a KEIN-WORD and a noun has to pick up the characteristic letter. the "r" in "der" is characteristic for masculine nouns the "e" in "die" is characteristic for feminine nouns the "s" in "das" is characteristic for neuter nouns mein deine ein keine guter warme kaltes guten Wein Milch Bier Studenten If an adjective is preceded by an KEIN-WORD, the ending before a noun in the singular is "-er" for masculine, "-es" for neuter and "-e" for feminine nouns. Before a plural noun the ending is "-en". III. Adjectives NOT preceded by either a KEIN-WORD or a DER-WORD Das ist guter Das ist warme Das ist kaltes Sind das gute Wein. Milch. Bier. Studenten If an adjective is not preceded by a KEIN- or DER-WORD, adjective endings before a noun in the singular are "-er" for masculine, "-es" for neuter and "-e" for feminine nouns. Before plural nouns it is "-e"! 17 18 GRAMMAR ZAHLEN < Numbers above 100 100 einhundert hundert 1000 eintausend tausend 1 000 000 (eine) Million 1 000 000 000 (eine) Milliarde 115 einhundertundfünfzehn hundertfünfzehn eintausendeinhundertundfünfzehn tausendeinhundertfünfzehn 1115 In German, a comma is used to set off decimals: 1,3 (eins Komma drei) Large numbers are usually grouped in blocks of 3 digits: 20 000 000 ORDINALZAHLEN __________________ < The numbers used in counting are cardinal numbers (Kardinalzahlen). When things are placed in order, first, second, third, etc., one uses ordinal numbers. In German, they are usually formed by adding "-t" onto the cardinal numbers. There are some exceptions: erstzweitdritt- first second third viertfünftsechst- siebtachtneunt- zehntelftzwölft- From "twentieth" and higher "-st" is added to the number: zwanzigstdreißigstsiebzigst- einundzwanzigst- zweiundzwanzigstvierzigstfünfzigstsechzigstachzigstneunzigst- hunderst- Most ordinal numbers are adjectives and are never used without endings. 19 Ordinal numbers not written out as words appear as numbers followed by a period: 1. = 1st 2. = 2nd 3. = 3rd 4. = 4th etc. Date: Ordinal numbers are used in German for writing the date; January 1, 1997 is often written like this: 1. 1. 97 15. 11. 97 (first day of the first month of 1997) (November 15, 1996) The first number refers always to the day, the second to the month, the last to the year. Written out, like in a letter, it looks like this: Wolfville, den 15. November 1997 Es gibt / gern / man < Es gibt The expression “es gibt” (from the verb “geben” = to give) means “there exists”, but is usually represented in English by “there is” (singular) or “there are” (plural) Es gibt nur eine Universität in Wolfville. (There is only one University in Wolfville.) Es gibt keine blauen Äpfel. (There are no blue apples.) gern The adverb “gern” can be added to many verbs and it changes the meaning in the sense of “to like to do” something. In English “to like” precedes the verb expressing what is liked, in German “gern” follows the verb. Alex liest gern Bücher. (Alex likes to read books) Gordon hört gern Jazz. (Gordon likes to listen to Jazz.) man The German pronoun “man” is used for an unspecific person. It is always impersonal and used in the 3rd person singular (like er, sie, es). Its English equivalent is usually “one”, sometimes “they” , “people”, ”we” or “you”. In diesem Seminar lernt man viel. (In this seminar one learns a lot.) Man sagt, Heidelberg ist eine schöne Stadt. (They say, H. is a beautiful city.) 20 Accusative < When we speak about actions, i.e. what somebody or something is doing, we imply the "doer" of the action as well as the receiver of the action. In this sentence "Ich hole eine Pizza." subject case (NOMINATIVE), direct object case (ACCUSATIVE). the "doer" (Ich), the subject, is in the the object of the action (die Pizza) is in the A large majority of verbs both in English and in German take a direct object. NOTE: the verbs "sein" (to be) and "heißen" (to be called) do not take a direct object. What follows "sein" and "heißen" is the subjective complement (in the NOMINATIVE): Dieser Mann heißt Herr Mayer. Max ist ein guter Mechaniker. Only the article word of a masculine noun is visibly different from the nominative. In the accusative "der" changes to "den", "ein" to "einen" ("kein" to "keinen" etc.). Masculine Feminine Neuter Plural NOMINATIVE der Pullover ein Pullover kein Pullover die Jacke eine Jacke keine Jacke das Buch ein Buch kein Buch die Bücher --Bücher keine Bücher ACCUSATIVE den Pullover die Jacke einen Pullover eine Jacke keinen Pullover keine Jacke das Buch ein Buch kein Buch die Bücher --Bücher keine Bücher The possessives ("mein", "dein", etc.), too, add an "-en" for the masculine singular in the accusative: Masculine meinen Pullover deinen Pullover seinen Pullover ihren Pullover unseren Pullover euren Pullover ihren Pullover Feminine meine Jacke deine Jacke seine Jacke ihre Jacke unsere Jacke eure Jacke ihre Jacke Neuter mein Auto dein Auto sein Auto ihr Auto unser Auto euer Auto ihr Auto 21 Plural meine Autos deine Jacken seine Pullover ihre Jacken unsere Autos eure Pullover ihre Autos Interrogatives < The interrogative for the "doer", the subject, is "wer" (for persons) and "was" (for things). When you ask about the receiver of an action, the direct object, the interrogative is "wen" (for persons) and "was" (for things), the same as English "whom" and "what": Nominative Accusative Wer ist das? Was ist das? Wen fragst du? Was holt er? Accusative pronouns < The pronouns in the nominative: ich, du, er, sie, es, wir, ihr, sie, (Sie) These pronouns also have a form for the accusative: 1. 2. 3. singular mich dich ihn sie es plural uns euch (Sie) (Sie) sie Of course, these pronouns (like the ones in nominative) are used when something specific is meant: "Hertie" verkauft den neuen Sony-Walkman. ("Hertie" sells the new Sony-Walkman) Er kostet 200 Euro. Kaufst du ihn? (It costs 200 euros.) (Are you going to buy it?) Prepositions with accusative < There are six prepositions which require the use of the accusative: bis until Er wohnt bis nächsten Mai in Deutschland. (He lives in Germany until next May.) durch through Stefan geht durch das Kaufhaus. (Stefan walks through the department store.) für for Peter lernt heute für einen Test. (Peter studies for a test today.) gegen against Sie sind gegen diesen Politiker. 22 (They are against this politician.) ohne without Frau Maier kommt ohne ihren Mann. (Frau Maier comes without her husband.) um around Die Mutter geht um den Tisch. (Mother walks around the table.) at (time) Seine Freundin möchte um 6 Uhr kommen. (His girl-friend would like to come at six o'clock.) Adjective endings in the accusative < The weak adjective endings in the accusative are like the weak nominative endings, except for the masculine ending: NOM: Autos ACC: Autos masculine feminine neuter der rote Mantel die gelbe Jacke das gute Auto die ein roter Mantel eine gelbe Jacke ein rotes Auto keine guten Autos den roten Mantel die gelbe Jacke das gute Auto die ein gutes Auto keine guten Autos einen roten Mantel eine gelbe Jacke plural guten guten The characteristic (strong) endings are the same one finds on the definite articles: masculine Nominative Accusative -er -en feminine -e -e Nominative: Das ist guter Wein. Das ist kalte Milch. Das ist dunkles Bier. Das sind alte Freunde. neuter plural -es -es -e -e Accusative: Er trinkt guten Wein. Sie holt kalte Milch. Wir kaufen dunkles Bier. Er sieht alte Freunde. DER-Words < 23 "DER-Words" ("dies-" and "welch-") are declined the same way as "der", "die", "das"; "die", that is, they get the same characteristic endings, in the nominative as well as the accusative. Masculine NOM: welcher Film dieser Film ACC: welchen Film diesen Film Feminine Neuter All Plurals welche Klasse diese Klasse welche Klasse diese Klasse welches Buch dieses Buch welches Buch dieses Buch welche Filme diese Filme welche Filme diese Filme Nominative Wo ist der Mantel? Welcher? Dieser. Accusative Möchten Sie den Mantel? Welchen? Diesen. There are more "DER-Words": "jede/r/s" and "alle" "Jede/r/s" means "each" or "every" and can only be used in the singular. "Alle", its counterpart in a way, only picks up the plural endings. Masculine dieser jeder ---diesen jeden ---- Nominative Accusative Feminine diese jede ---diese jede ---- Neuter dieses jedes ---dieses jedes ---- Plural diese ---alle diese ---alle Position of "nicht" The negating word "nicht" is usually placed in front of the element of the sentence which one wishes to negate: Der Tisch ist nicht groß. Ich bin heute nicht hier. (The table isn't big.) (I'm not here today) When the sentence contains a direct object, however, it is normally placed after the direct object (especially when the direct object is a pronoun): Ich habe das Radio nicht. (I don't have the radio) Ich habe es nicht. (I don't have it.) The verb-form "möchte" 24 "Möchte" comes from the verb "mögen" (which we will treat in detail later) and means "would like to". It is a helping (auxiliary) verb that is often accompanied by another verb, a so-called infinitive completion, which is placed at the end of the sentence: Ich möchte einen Wintermantel kaufen. Wir möchten nach München fahren. (I would like to buy a winter coat) (We would like to go to Munich) The verb "möchte" can also be used a. alone in the sense "I would like to have", where the infinitive "have" is left out b. when the infinitive is understood: a. Ich möchte ein Glas Wasser (haben). (I would like [to have] a glass of water) b. Er möchte nach Hause (gehen). (He would like to go home) "Möchte" has an irregular form in its conjugation. The third person singular does not have the usual "-t" ending Singular Plural_____ 1. ich möchte wir möchten 2. du möchtest ihr möchtet 3. er, sie, es möchte sie möchten Expressions of time < Expressions of time (if they do not follow prepositions that require other cases) are in the accusative case: Marlies fährt jeden Tag nach Köln. (Marlies drives to Cologne every day.) Gerhard studiert nächstes Jahr in Wien. (Gerhard is going to study in Vienna next year) Ich bin diesen Samstag in Stuttgart. (I'm in Stuttgart this Saturday.) GRAMMATIK 1: The Present Perfect Tense The present perfect tense is the tense normally used in German to talk about events in the past. It is a compound tense, that is, it consists of two parts: 1. the auxiliary ("haben" or "sein") in normal second place position in the sentence 2. and the past participle, which usually begins with the prefix ge- and ends with the suffixes –t or –en. The past participle is always at the end of the sentence. 25 Ich habe meinen Mantel geholt. Hast du den Mercedes gekauft? Er ist nach Berlin gefahren. It is the auxiliary that is conjugated according to person and number (2nd person singular, 3rd person plural, etc.); the participle remains the same. Er hat seinen Mantel geholt. Was hast du gestern gegessen? Wir sind nach Berlin gefahren. Past Participle of REGULAR Verbs Regular verbs generally form their past participle by adding the prefix ge- and the ending -t to the verb stem. Verbs with stems ending in -d or -t add -et. infinitive stem auxiliary and past participle kaufen kosten reisen kaufkostreis- hat gekauft hat gekostet ist gereist Verbs ending in the suffix -ieren do not add the prefix ge- in the past participle! reparieren studieren telefonieren reparstudiertelefon- hat repariert hat studiert hat telefoniert Past Participle of IRREGULAR Verbs There are many verbs in the German language that do not follow the regular pattern of past participle formation. These irregular verbs generally form their past participle by adding the prefix ge- and the ending -n or -en to the verb stem. In addition, many irregular verbs change their stem vowel and occasionally some consonants in the stem. For this reason, the past participle of each irregular verb will be listed in the vocabulary section and must be memorized. IRREGULAR VERBS CHAPTER 1-6 VERB Conjugation Pattern of verbs with stem vowel change: PAST PARTICIPLE 26 English anrufen beginnen behalten bekommen bleiben bringen essen fahren finden fliegen geben gehen kennen kommen laufen lesen nehmen schlafen schreiben schwimmen sehen sein sprechen steigen tragen treffen trinken verbringen vergessen werden er behält er isst er fährt er gibt er läuft er liest er nimmt er schläft er sieht irregular er spricht er trägt er trifft er vergisst du wirst / er wird hat angerufen hat begonnen hat behalten hat bekommen ist geblieben hat gebracht hat gegessen ist gefahren hat gefunden ist geflogen hat gegeben ist gegangen hat gekannt ist gekommen ist gelaufen hat gelesen hat genommen hat geschlafen hat geschrieben ist geschwommen hat gesehen ist gewesen hat gesprochen ist gestiegen hat getragen hat getroffen hat getrunken hat verbracht hat vergessen ist geworden to call to begin to keep to receive, get to stay, remain to bring to eat to drive to find to fly to give to go, walk to know to come to run, go to read to take to sleep to write to swim to see to be to speak to climb to wear, carry to meet to drink to spend to forget to become The use of the auxiliary verb "sein" with the past participle Some German verbs use "sein" rather than "haben" as their auxiliary verb in the present perfect tense: Sie ist gestern nach Halifax gefahren. Du bist viel zu früh gekommen. These verbs fulfill two conditions: 1. 2. They are intransitive (they do not take a direct object). They indicate change of location or condition. Er ist zum Postamt gelaufen. change of location (irregular verb) (He ran to the post office.) Wir sind nach Bonn gereist. change of location (regular verb) 27 (We traveled to Bonn.) Ich bin um 7 Uhr aufgewacht. (I woke up at 7 o’clock.) change of condition (regular verb) Erika ist Lehrerin gewesen. change of condition (irregular verb) (Erika was a teacher.) NOTE: Whether a verb is irregular or regular does NOT determine the use of "haben" or "sein" as an auxiliary. Both regular (i.e.:"reisen") and irregular verbs (i.e.:"fahren") may use the auxiliary "sein". Wir sind letztes Jahr durch Deutschland gereist. Mein Vater ist gestern nach Toronto gefahren. There are two common verbs that are exceptions to this rule. Both do not show motion nor change of condition but still use "sein" as auxiliary in the present perfect tense: 1. 2. sein (to be) bleiben (to stay, remain) Ich bin in der Stadt gewesen. Du bist zu Hause geblieben. GRAMMATIK 2: Separable and Inseparable Prefixes Inseparable Prefixes An inseparable prefix is normally a two- or three-letter syllable at the beginning of a verb. bekommen (to receive, get), erzählen (to tell), entschuldigen (to excuse), missverstehen (to misunderstand), vergessen (to forget), zerbrechen (to break) Inseparable prefixes do not separate from the verb when the verb is conjugated: Peter bekommt morgen einen Brief. Sie erzählt eine schöne Geschichte. Mein Freund vergisst seinen Pass. (Peter will get a letter tomorrow) (She's telling a nice story) (My friend forgets his passport) 28 These are the most frequently used prefixes: be- / er- / ent- / miss- / ver- / zer- Separable Prefixes Separable prefixes are joined to the verb only in the infinitive form. Otherwise they separate from the conjugated form of the verb and are placed at the end of the clause. Mark Twain uses the verb to depart, in German: abfahren or abreisen ; one word in the infinitive but used in a sentence the prefix ab separates from the verb and is placed at the end of the clause: Der Zug fährt gleich ab. (The train will depart soon) As Twain points out there is quite a number of separable prefixes in German. They are themselves words, especially prepositions or adverbs like "mit", for example, which means "with" (as a preposition) or "along" (as a prefix). Sie bringt ihren Freund mit. (She is bringing her friend along.) Some of the more frequently used separable prefixes are: ab off, away an on, at auf up, open aus out of ein the prefix form of "in" her toward hin away mit with, along um indicating change weg away weiter further, continue Wir fahren morgen früh ab. (We are leaving tomorrow morning.) Peter kommt um drei Uhr an. (Peter arrives at 3 o'clock.) Die Studenten machen die Bücher auf. (The students are opening their books.) Chris steigt in Zürich aus. (Chris gets out [of the train] in Zürich.) Andrea steigt gleich ein. (Andrea gets in [the train] right away.) Komm bitte her! (Come here, please.) Am Dienstag fahren wir dort hin. (Tuesday we'll go there.) Kommst du mit? (Are you coming along?) Klaus steigt in Basel um. (Klaus changes [trains] in Basel.) Torsten fährt übermorgen weg. (Torsten goes away the day after tomorrow.) Nach einer Minute liest sie weiter. 29 zu to or closed zurück back (After a minute, she continues to read.) Machen Sie bitte die Tür zu! (Close the door, please.) Wann kommst du heute abend zurück? (When will you come back tonight?) The meaning of these prefixes is not always the same. It may change depending on the verb they are affixed to. (i.e."zumachen" means "to close" , "zusprechen" means "to encourage") Present Perfect Tense of verbs with inseparable and separable prefixes Verbs with inseparable prefixes also do not add the prefix ge- in the past participle. besuchen behalten hat besucht hat behalten Verbs with separable prefixes have the ge- inserted between prefix and verb. einkaufen hat eingekauft aussteigen ist ausgestiegen 30 GRAMMATIK DATIVE CASE < In addition to the nominative (subject) case and the accusative (direct object) case German has another case: the DATIVE CASE. The DATIVE CASE has three main functions: A. B C. it is used after certain prepositions it is used to denote the indirect object and it is used in certain idiomatic expressions and after certain verbs Once more it is primarily the article that changes in the DATIVE CASE as seen in the following table. (Nominative and accusative are also given for the sake of contrast.) Masculine Feminine Neuter Plural NOMINATIVE der Mann ein Mann die Frau eine Frau das Kind ein Kind die Männer keine Frauen ACCUSATIVE den Mann einen Mann die Frau eine Frau das Kind ein Kind die Kinder keine Kinder DATIVE dem Mann der Frau dem Kind einem Mann einer Frau einem Kind den Männern den Frauen den Kindern keinen Männern NOTE: To form the dative in the plural the noun picks up an "-n", if it does not already have one in the nominative plural form ( exceptions are names : “den Meyers” and nouns with foreign roots: “den Autos”, “den Kameras”. ADJECTIVE ENDING In the DATIVE all modifying adjectives following an article word end in -en dem (einem) der (einer) dem (einem) den (keinen) dicken Mann großen Frau kleinen Kind interessanten Männern 31 DATIVE CASE PRONOUNS _______ < The pronouns for the subject case (NOMINATIVE) and the direct object case (ACCUSATIVE) have already been introduced. Here they are listed again plus the DATIVE CASE PRONOUNS. SINGULAR PLURAL Nom. Acc. Dat. Nom. Acc. Dat. 1. ich mich mir wir uns uns 2. du dich dir ihr euch euch 3. er ihn ihm sie sie ihnen sie sie ihr es es ihm Sie Sie Ihnen 2. person formal (singular / plural) DATIVE CASE INTERROGATIVES < There is only one interrogative form for the DATIVE CASE: wem Examples: to whom, for whom Wem gehört der Audi? Wem schenkst du das Buch? To whom does the Audi belong? To whom do you give the book? DATIVE CASE PREPOSITIONS < After the following nine prepositions one must use the DATIVE CASE. aus (out of) Er kommt gleich aus dem Kino. (Soon he'll come out of the movie theatre) (from) Jan kommt aus Berlin. (Jan is from Berlin.) außer (besides) Sie hat außer dem Audi noch einen VW. (Besides the Audi she owns a VW.) bei (near) Das Kaufhaus steht bei der Post. (The department store is situated near the post office.) (at) Richard arbeitet bei Siemens. 32 (Richard works at Siemens.) (at the house of) Wir sind heute bei unseren Freunden. (Today, we are at our friends’ house/place.) gegenüber (opposite) Meine Wohnung ist gegenüber dem Kino. (My apartment is opposite the movie theatre.) mit (with) Helga spielt mit ihren Freunden. (Helga plays with her friends.) nach (to) Fährt Manfred morgen nach Köln? (Is Manfred going to Cologne tomorrow?) (after) Nach der Schule spielen die Kinder hier. (The kids play here after school.) seit (since) Karl studiert seit 1994 in Hamburg. Carl has been studying in Hamburg since 1994.) (for) Ich wohne seit zwei Monaten in Bonn. (I have been living in Bonn for two month.) von (from) Sie kommt von dem [vom] Postamt. (She's coming from the post office.) (by) Das Buch ist von Thomas Mann. (The book is by Thomas Mann.) (of, about) Die Studenten sprechen von ihrer Arbeit. (The students talk about their work.) zu (to) Ich fahre zu dem [zum] Einkaufszentrum. (I'm driving to the shopping centre.) (to my place) Kommt ihr heute Abend zu mir?. (Are you coming to my place tonight.) CONTRACTIONS of DATIVE PREPOSITIONS < The prepositions "bei", "von" and "zu" often contract with the definite article dem, and "zu" also contracts with the definite article der. bei dem beim Frau Schneider wohnt beim Kino. (Mrs. Schneider lives near the movie theatre.) von dem vom Sie kommt vom Postamt. (She comes from the post office.) zu dem zum Geht ihr zum Einkaufszentrum? (Are you going to the shopping centre?) zu der zur Ich fahre jetzt zur Universität. (I'm driving to the university now.) VERBS with the DATIVE CASE < 33 The following verbs take a so-called DATIVE-OBJECT, not a direct object. antworten (to answer) Er antwortet dem Lehrer. (He answers the teacher.) danken (to thank) Sie dankt ihrem Freund für den Brief. (She thanks her friend for the letter.) gefallen gehören (to please) (to appeal to) Der Film gefällt meiner Schwester. (to belong) Das Buch gehört seiner Professorin. (The film appeals to my sister./My sister likes the film.) (The book belongs to his professor.) gratulieren (to congratulate) Sie gratulieren ihren Kindern. (They congratulate their children.) helfen (to help) Ich helfe den Touristen. (I help the tourists.) passen (to fit) Der Pullover passt meiner Frau. (The sweater fits my wife.) (to be convenient, used with „es“) Um wie viel Uhr passt es deinem Lehrer? (At what time is it convenient for your teacher?) The verb "glauben" takes an indirect object only when it refers to persons. glauben (to believe someone) Ich glaube deinem Freund nicht. (I don't believe your friend.) BUT: glauben (to believe something) Ich glaube diese Geschichte nicht. (I don't believe this story.) EXPRESSIONS with the DATIVE CASE < There are several very common expressions in German which use the DATIVE: Wie geht es Ihnen (dir, euch)? How are you? Es geht mir gut. I am fine. Es tut mir leid. I am sorry. The DATIVE CASE is also used to denote the INDIRECT OBJECTS < 34 The accusative case identifies the receiver of the action (the direct object). The DATIVE case identifies the indirect object. It is usually a person (or group of persons, an organization, etc.) who does not receive but is indirectly involved with the action expressed by the verb. In most instances one could say that the indirect object denotes the beneficiary of an action: SUBJECT VERB INDIRECT DIRECT OBJECT OBJECT Ich gebe dem Professor das Buch. I give the professor the book. or I give the book to the professor. NOTE:English has two ways of expressing the beneficiary: 1. the prepositional phrase "...to the professor" or 2. the pure dative case (without the preposition). German, much more than English, prefers the pure dative case (that is indirect objects). Many verbs that take a direct object can also pick up an indirect object. When both the direct and the indirect objects in a sentence are nouns, the indirect object (DATIVE CASE) is placed before the direct object (ACCUSATIVE CASE): indirect object direct object Ich schreibe einen Brief. Ich schreibe meiner Freundin einen Brief. (I write a letter.) ( I write my girlfriend a letter) Er holt ein Glas Wasser. Er holt der alten Frau ein Glas Wasser. (He gets a glas of water.) (He gets the old lady a glass of water.) Sie kauft eine Jacke. Sie kauft ihrem Freund eine Jacke. (She buys a jacket.) (She buys her friend a jacket.) Wir schenken immer Bücher. Wir schenken unseren Eltern immer Bücher. (We always give books as presents) (We always give our parents books as presents.) Schickst du eine Email? Schickst du mir eine Email? (Do you send an email?) (Are you sending me an email? NOTE: The rule of thumb is: the indirect object precedes the direct object. 35 Ich kaufe meiner Freundin diese Jacke. If, however, one object happens to be a pronoun, then it precedes the other object: Ich kaufe meiner Freundin diese Jacke. Ich kaufe ihr diese Jacke. Ich kaufe sie meiner Freundin. If both objects are pronouns, the ACCUSATIVE precedes the DATIVE: Ich kaufe meiner Freundin diese Jacke. Ich kaufe sie ihr. Double pronoun combinations like these are not very frequent and combinations, that sound alike i.e. ihn/ihm or ihn/ihr are avoided altogether. Verbal nouns (infinitives used as nouns) < The infinitive of a verb may take over the function of a noun in a sentence. It then becomes a neuter noun and may be used with article words and prepositions. The English equivalents of these nouns normally end in "-ing", e.g. Einkaufen = shopping; Schwimmen = swimming; vor dem Einkaufen = before shopping; nach dem Schwimmen = after swimming, etc. Common combinations are the prepositions "bei","von" und "zu" with verbal nouns: beim Essen (at/during the meal, while eating), zum Einkaufen gehen (to go shopping) vom Schwimmen kommen (to come from swimming). EXAMPLES: Nach dem Einkaufen bin ich immer müde. (After shopping I'm always tired.) Das Schwimmen macht Spaß. (Swimming is fun.) Hörst du Musik beim Lernen? (Do you listen to music while studying?) Ich gehe später zum Skifahren. (I go skiing later.) Peter kommt vom Schlittschuhlaufen zurück. (Peter is coming back from skating.) 36 GRAMMATIK 1: The Present Perfect Tense A list of strong and irregular weak verbs so far introduced (including Kapitel Acht): infinitive 3rd person sg. (depart) (begin) (arrive) (call [on phone]) (give up) (write down) (get up) (spend [money]) (get out, climb out) (begin) (keep) (get, receive) (stay, remain) (bring) (invite) (get in, climb in) (eat) (drive, go) (watch TV) (find) (fly) (give) (appeal to, like) (walk, go) (help) (come out) (come down) (climb up) (go in) (know – s.o.) (come) (run, walk) (read) (drive off) (bring along) (drive along) (take along) (take) ab/fahren an/fangen an/kommen an/rufen auf/geben auf/schreiben auf/stehen aus/geben aus/steigen beginnen behalten bekommen bleiben bringen ein/laden ein/steigen essen fahren fern/sehen finden fliegen geben gefallen gehen helfen heraus/kommen herunter/kommen hinauf/steigen hinein/gehen kennen kommen laufen lesen los/fahren mit/bringen mit/fahren mit/nehmen nehmen fährt...ab fängt...an (sleep) (write) (swim) schlafen schreiben schwimmen schläft aux. + past participle ist abgefahren hat angefangen ist angekommen hat angerufen gibt ... auf hat aufgegeben hat aufgeschrieben ist aufgestanden gibt ... aus hat ausgegeben ist ausgestiegen hat begonnen behält hat behalten hat bekommen ist geblieben hat gebracht lädt...ein hat eingeladen ist eingestiegen isst hat gegessen fährt ist gefahren sieht ... fern hat ferngesehen hat gefunden ist geflogen gibt hat gegeben gefällt hat gefallen ist gegangen hilft hat geholfen kommt ... heraus ist herausgekommen kommt ... herunter ist heruntergekommen steigt ... hinauf ist hinaufgestiegen geht ... hinein ist hineingegangen hat gekannt ist gekommen läuft ist gelaufen liest hat gelesen fährt ... los ist losgefahren hat mitgebracht fährt ... mit ist mitgefahren nimmt ... mit hat mitgenommen nimmt hat genommen 37 hat geschlafen hat geschrieben ist geschwommen (see) sehen sieht hat gesehen (be) sein ist ist gewesen (sit) sitzen hat gesessen (speak) sprechen spricht hat gesprochen (stand) stehen hat gestanden (wear, carry) tragen trägt hat getragen (meet) treffen trifft hat getroffen (drink) trinken hat getrunken (do) tun hat getan (change [trains etc.]) um/steigen steigt ... um ist umgestiegen (to move) um/ziehen ist umgezogen (spend [time]) verbringen hat verbracht (forget) vergessen vergisst hat vergessen (pass on) weiter/geben gibt ... weiter hat weitergegeben (become) werden wird ist geworden (drive back) zurück/fahren fährt...zurück ist zurückgefahren GRAMMATIK 2: Special Prefixes “hin” und “her” The prefixes "hin" and "her" I. _______________________________ These prefixes deserve special attention. "Hin" indicates movement away from the point of reference. "Her" means movement towards the point of reference: (usually the speaker): Sie fährt heute hin. (She is going there today.) II. < Sie kommt heute her. (She is coming here today.) The prefixes "hin" and "her" can combine with other separable prefixes forming double prefixes. These prefixes, usually denoting position, are made more precise by this addition: 38 Hans geht hinauf. Hans kommt herunter. The prefix "hinauf" denotes both "up" and "away" from the point of reference. The prefix "herunter" indicates "down" and "towards" the speaker, at the bottom of the stairs. The speaker standing at the top of the stairs would be saying: Hans kommt herauf. Hans geht hinunter. The verb "kommen", of course, already implies "her" and "gehen" implies "hin". The prefixes "auf" (up) and "unter" (under) are not the only ones "hin" or "her" can combine with, although they are found quite frequently. hineingehen herauskommen Die Leute gehen hinein. Wer kommt heraus? NOTE: when an infinitive with separable prefix is used as an infinitive completion the prefix is joined to the main part of the infinitive: Ich möchte nach Bremen zurückfahren. Herr Maier möchte hereinkommen. (I would like to go back to Bremen.) (Mr. Maier would like to come in.) GRAMMATIK 3: Command Forms Commands < 39 There are three forms for the German command (imperative), one for the formal form of address and two for the familiar form of address, one each for singular and plural. 1. FORMAL FORM Sprechen Sie lauter! (Speak up!) Vergessen Sie Ihr Buch nicht! (Don't forget your book!) Steigen Sie ein! (Get in!) Machen Sie das nicht! (Don't do that!) Rufen Sie mich an! (Call me!) Contrary to English, this imperative uses the personal pronoun "Sie". An exclamation mark may be added for urgency. 2. FAMILIAR SINGULAR FORM Steig ein! (Get in!) Mach das nicht! (Don't do that!) Ruf mich an! (Call me!) The familiar singular form of the command uses the stem of the verb without an ending. 3. FAMILIAR PLURAL FORM Steigt ein! (Get in!) Macht das nicht! (Don't do that!) Ruft mich an! (Call me!) The familiar plural form of the command uses the stem of the verb with the ending –t. 40 Note: Verbs with stems ending in -t, -d add an –e to the stem: (Don’t work too much! - sing.) (Don’t work too much! - pl.) Arbeite nicht so viel! Arbeitet nicht so viel! Strong verbs with a vowel change in the present tense (i.e. "sprechen", "geben", "essen") maintain that change only in the familiar command form singular: Sprich lauter! Lies das Buch! Vergiss die Fahrkarten nicht! (Speak louder!) (Read the book!) (Don’t forget the tickets!) No change occurs in the plural forms: Sprecht lauter! Lest das Buch! Vergesst die Fahrkarten nicht! (Speak louder!) (Read the book!) (Don’t forget the tickets!) Verbs with a vowel change from "a" to "ä" are an exception. In the command form there is NO umlaut: Schlaf jetzt! Fahr jetzt los! (Sleep now!) (Drive off now!) Familiar command form plural: Schlaft jetzt! Fahrt jetzt los! (Sleep now!) (Drive off now!) The word "DOCH" is often added to soften the imperative statements. It carries the meaning "why don't you": Steigen Sie doch ein! Ruft mich doch an! Sprich doch lauter! GRAMMATIK 4: Polite Requests 41 POLITE REQUESTS < There is a way of asking someone to do something without using a command, which might sound too forceful. It uses the conditional form of the auxiliary "werden": "würde" (would). This form is conjugated like "möchte": singular plural ich würde wir würden du würdest ihr er sie es würde sie würden würdet The construction of a sentence with "würde" is also similar to that with "möchte": Möchten Sie die Zeitung lesen? (Would you like to read the newspaper?) Würden Sie mich heute Abend anrufen? (Would you call me tonight?) Würdest du mich bitte hinfahren? (Would you drive me there, please?) Würdet ihr bitte einsteigen? (Would you get in, please?) 42 GRAMMATIK There are six verbs known as modal auxiliaries: können müssen sollen wollen dürfen mögen (to be able to, "can") (to have to, must) (to be supposed to, should) (to want to) (to be allowed to, may) (to like) As in English these verbs really describe what might be called an "attitude" toward another action: I want to give a party. This sentence does not say you give a party; it describes your feelings, your desire to give a party. The same in the German sentence: Ich will eine Party machen. Since these modals describe attitudes toward actions, they are usually not used alone but need a completion in the form of an infinitive. One cannot really say: "I must." alone, without some other action at least being understood: "I must work (write letters, visit my friends, etc.)". In German the infinitive completion always goes at the end of the sentence without "zu" - "to"! Er kann deinen Freund heute Abend nicht sehen. The conjugation of the modal auxiliaries differs from the regular German verb conjugation. dürfen sg. 1. 2. 3. ich du er sie es darf darfst können pl. sg. wir dürfen ihr dürft sie dürfen ich du er sie es darf (Sie dürfen) mögen 1. 2. 3. ich du er sie es mag magst pl. kann kannst wir können ihr könnt sie können kann (Sie können) müssen wir mögen ihr mögt sie mögen ich du er sie es mag (Sie mögen) sollen muss musst muss wollen 43 wir müssen ihr müsst sie müssen (Sie müssen) sg. 1. 2. 3. ich du er sie es soll sollst pl. sg. wir sollen ihr sollt sie sollen ich du er sie es soll (Sie sollen) pl. will willst wir wollen ihr wollt sie wollen will (Sie wollen) Note the vowel change in the singular (in some modals) and the missing "e" and "t" endings in the 1st and 3rd persons singular! Negative of "müssen" and "dürfen" English "must" and "have to" have the same meaning in positive sentences but not in negative ones. So there are different German equivalents. Positive: Ich muss gehen. Ich darf gehen. Negative: Ich muss nicht gehen. Ich darf nicht gehen. I must go. I have to go. I may go. I'm allowed to go. I don't have to go. I must not go. Present perfect tense of modal auxiliaries Modal verbs are usually used with a dependent infinitive. Ich muß sehr viel schreiben. Wir wollen nach Hause gehen. Instead of changing to a past participle when used in the prsent perfect tense, the modal verbs follow the dependent infinitive as another infinitive. The auxiliary for all modals in the present perfect tense is "haben". Ich habe sehr viel schreiben müssen. Wir haben nach Hause gehen wollen. Only when there is no dependent infinitive, the modals may form past participles. All modal verbs are weak and have past participles on the pattern ge________t, but the Umlaut of the infinitive disappears. dürfen Karl hat das nicht gedurft. können Das hat er nicht gekonnt. mögenSie hat mich nicht gemocht. 44 müssen wollen Hast du das wirklich gemusst? Ich habe das nicht gewollt! The modal "sollen" is not used as a participle. Omission of the infinitive completion with modals The infinitive completion is often omitted in sentences with a modal when the meaning of the infinitive is clear from the context. Ich kann es nicht. (I can't.) = Ich kann es nicht tun (I can't do it.) Ich muss nach Hause. (I have to go home.) = Ich muss nach Hause gehen. (I have to go home.) DO NOT CONFUSE a. “wollen” (to want to) or b. „ich will", "er, sie, es will" with the English "will" (future tense). "mögen" (to like) with "möchten" (would like) The German verb "wollen" means "to want to"! ================================================================= The verb "wissen" Another verb, "wissen" (to know), - although not a modal auxiliary - is conjugated like the modals: wissen sg. pl. 1. 2. 3. ich du er sie es weiß weißt wir ihr sie wissen wisst wissen (Sie wissen) weiß Note the lack of endings on the first and third persons, singular. "wissen", "kennen" und "können" 45 The English equivalent of both "wissen" and "kennen" is "to know"; "wissen" means to know something as a fact "kennen" means to be acquainted with a person, place or thing. "können" means "to be able to do something" Ich weiß, wer Frau Bauer ist. Ich kenne Frau Bauer gut. Ich kann sehr gut Italienisch. I know who Mrs. Bauer is. I know Mrs. Bauer well. I know Italian very well. ("kennen" was used in Middle English and is still used in Scottish. The noun "ken" means perception or understanding: "That's beyond my ken.") Other infinitive completions Modal auxiliaries are not the only verbs to take infinitive completions. Many other verbs do, too. The big difference is that almost all verbs other than the modals (and "möchten" + "würden") take the word "zu" with the infinitive: Ich versuche, deine Tasche zu finden. Es ist schwer, Japanisch zu lernen. Es ist schön, nichts machen zu müssen. (I try to find your bag.) (It is difficult to learn Japanese.) (It is nice not having to do anything.) (In the last example the modal is an infinitive completion not the main verb!) When the infinitive completion is a verb with a separable prefix, then "zu" is inserted between the prefix and the stem of the infinitive: Max versucht, die Tür aufzumachen. (Max tries to open the door.) "Um ... zu" + infinitive construction The preposition "um" is used in a construction with the infinitive to express purpose (in order to). One action is done to achieve another. The infinitive is placed at the end of the sentence as usual and is always preceded by "zu"; anything else, direct objects, prepositional phrases, etc., is placed in between "um" and "zu" + infinitive (this infinitive constructions is separated from the main clause by a comma): Ich borge sein Auto, um nach Bonn zu fahren. (I borrow his car [in order] to drive to Bonn.) Oliver braucht noch Käse, um eine Pizza zu machen. (Oliver still needs cheese [in order] to make a pizza.) Seine Freundin geht zum Metzger, um Wurst zu kaufen. (His [girl-] friend goes to the butcher shop [in order] to buy cold cuts.) This construction can only be used when the subject carrying out the action of the main 46 clause and the action in the infinitive construction are the same. Although the "um ... zu" + infinitive construction cannot stand alone separated from a main clause, in conversation it's often used without it: Warum brauchst du Harros Auto? (Why do you need Harro's car?) Um nach Bonn zu fahren. ([In order] to drive to Bonn.) "ein paar" + "einige" and "etwas" + "ein bisschen" a. The terms "ein paar" and "einige" mean "a few" or "some" and express an undefined number, more than two but not many. Möchtest du ein paar Weintrauben? Ich lade einige Freunde ein. b. (Would you like a few grapes?) (I'll invite some friends.) The meaning of "etwas" is determined by its function in a sentence. If "etwas" is used as an indefinite pronoun it refers to things and ideas and means "something". Ich muss jetzt etwas essen. (Now I have to eat something.) If "etwas" is used as an adjective preceding a noun it means "some". Möchten Sie etwas Wein? (Would you like some wine?) In this function "etwas" can be replaced by "ein bisschen" meaning "a little bit" Möchten Sie ein bisschen Wein? (Would you like a little bit of wine?) 47 GRAMMATIK Either/Or-Prepositions In previous chapters we studied prepositions which require the ACCUSATIVE: bis, durch, für, gegen, ohne, um and prepositions which require the DATIVE: aus, von, außer, mit, gegenüber, seit, nach, zu, bei Here is a group of prepositons which can be used EITHER with the accusative OR the dative. an auf in vor über unter hinter neben zwischen on (a vertical surface) on, to (rivers, lakes, sea) at, by (bordering at places) on, onto (horizontal surface) in, into in front of, before over, above under, below behind beside, next to between All these prepositions usually describe local relationships. The term "EITHER / OR PREPOSITIONS" refers to the fact that these prepositions require either the ACCUSATIVE case or the DATIVE case. If the verb describes a movement towards a certain goal or area and thereby implies a change of place, the noun or pronoun following one of these prepositions must be in the ACCUSATIVE case. The corresponding interrogative here is "wohin?" (where to?). If the verb expresses that someone or something remains in the same place, that there is no change of place including either no motion/movement or motion without a specific goal, the noun or pronoun following the above prepositions must be in the DATIVE case. The corresponding interrogative is then "wo?" (where?). NOTE: The verb in the dative case might include a motion within certain boundaries. To determine the correct case check if the object passes/crosses real or imaginary borders. 48 ACCUSATIVE : Wohin? Motion with goal - change of place Er geht ans Fenster. Sie geht auf die Straße. Das Flugzeug fliegt über die Stadt. (He goes to the window.) (She goes on to the street.) (The plane is passing over the city.) DATIVE : Wo? No motion Sie steht am Fenster. (She stands at the window) Sie steht auf der Straße. (She is standing on the street.) Motion with no goal - no change of place Er geht auf dem Schiff spazieren. (He is walking on the ship.) Sie geht auf der Straße. (She is walking on the street.) Das Flugzeug fliegt über der Stadt. (The plane is flying over the city.) The Verbs liegen/legen, sitzen/setzen, stehen/stellen, hängen and sein The verbs liegen, sitzen and stehen are strong verbs. They indicate that an either/orpreposition is followed by the dative case. The same is true for the verb sein. The verbs legen, setzen and stellen are weak verbs and they indicate the accusative case. The verb hängen can express both the action of hanging something and the position of 49 something hanging. Compare also the examples on the following page. Either/Or-Prepositions Preposition Akkusativ Dative an Markus geht an das Fenster. (Markus goes to the window.) Markus steht am Fenster. (Markus stands at the window.) auf Sie legt ihre Brille auf den Tisch. (She puts her glasses on the table.) Die Brille liegt auf dem Tisch. (The glasses are on the table.) hinter Wir stellen das Sofa hinter den Tisch. (We put the sofa behind the table) Das Sofa steht hinter dem Tisch. (The sofa stands behind the table.) in Er geht in das Geschäft. (He goes into the shop.) Er wartet im Geschäft. (He is waiting inside the shop.) neben Maja stellt den Stuhl neben das Fenster. (Maja puts the chair next to the window.) Der Stuhl steht neben dem Fenster. (The chair stands next to the window.) über Sabine hängt eine Lampe über den Tisch. (Sabine hangs a lamp over the table.) Eine Lampe hängt über dem Tisch. (A lamp is hanging over the table.) unter Der Hund geht unter das Bett. (The dog goes under the bed.) Der Hund ist unter dem Bett. The dog is under the bed. vor Der Bus fährt vor den Bahnhof. (The bus drives up in front of the train station.) Die Kinder spielen vor dem Haus. (The children are playing in front of the house.) zwischen Er stellt die Schachtel zwischen das Regal und den Kühlschrank. (He puts the box between the shelf and the fridge.) Die Schachtel steht zwischen dem Regal und dem Kühlschrank. (The box is between the shelf and the fridge.) Contractions with "either / or" prepositions The following contractions can be formed: Dative: an + dem = am Accusative: an + das = ans in + dem = im in + das = ins In colloquial German hinterm überm unterm vorm are often used in the dative and aufs hinters übers unters vors are often used in the accusative. 50