Aromastoffe in ausgewählten alltäglichen Lebensmitteln

Werbung

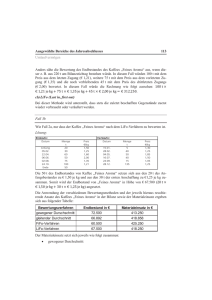

SCIENCE AND PRACTICE WISSENSCHAFT UND PRAXIS Aromastoffe in ausgewählten alltäglichen Lebensmitteln Flavouring substances in chosen daily consumed foodstuffs K. Eisinger, D. Majchrzak Zusammenfassung Summary Die vorliegende Arbeit bietet einen Überblick über die bisher auf dem Gebiet der Geruchsaromastoffe durchgeführten Studien zu Lebensmitteln, die im alltäglichen Verzehr vorkommen (Obst und Obstsäfte, Gemüse, Milch- und Milchprodukte, Getreideprodukte). Die Studienergebnisse wurden gegenübergestellt, um Unterschiede und Gemeinsamkeiten der Aromaprofile der ausgewählten Lebensmittel zu erhalten und vor allem jene Substanzen zu erheben, die für die Besonderheiten eines Aromas von Bedeutung sind. Jedes Lebensmittel weist ein charakteristisches Aroma auf, das sich aus einer Vielzahl an Aromastoffen in unterschiedlichen Konzentrationen zusammensetzt. Beim Vergleich verschiedener Sorten einer Lebensmittelgruppe wurden einige Aromakomponenten gefunden, die in allen Proben vorkamen und andere, die wiederum nur in einzelnen Sorten enthalten waren. Jene Substanzen, die nicht in allen analysierten Lebensmitteln vorkommen, können gemeinsam mit Konzentration und Schwellenwert des jeweiligen Stoffes für die Unterschiede der Aromen verantwortlich gemacht werden. The aim of this work was to develop a combination of the so far studies on aroma of foodstuffs which are used in the daily consumption (fruit and fruit juices, vegetables, milk and milk products, grain products). The findings of these studies have been compared to elevate the differences and similarities of the aroma profiles of chosen foods, especially those substances that are responsible for the characteristic attributes of the aroma. Each foodstuff shows a characteristic aroma that is composed of a multiplicity of flavouring substances. The comparison of different cultivars in one category of foodstuffs showed components that have been identified in each sample, some others only in single cultivars. The substances, that do not occur in each analysed foodstuff, combined with the concentrations and the thresholds of these substances, are responsible for the differences of the aroma. Kennwörter: Flavouring substance, aroma, flavour, daily-consumed foodstuffs Aromastoffe, Aroma, Flavour, alltägliche Lebensmittel 1. Einleitung und Fragestellung Die sensorische Qualität von Lebensmitteln umfasst die Merkmale Aussehen, Geruch, Geschmack und Textur [1], sie wird mit Hilfe des Gesichts-, Geruchs-, Geschmacks-, Tast- sowie des Gehörsinns beurteilt. Der Genusswert, welcher auch die Auswahl und Akzeptanz von Lebensmitteln beeinflusst, wird jedoch hauptsächlich durch das Aroma bestimmt [2]. Dieser Begriff bezeichnet den olfaktorischen und gustatorischen Gesamteindruck einer Probe [3], wobei ein Unterschied zum Geruch darin besteht, dass viele der beteiligten Stoffe erst beim Kauen freigesetzt werden und über die Nasen-Rachen-Verbindung zur Empfindung des Aromas beitragen. Das Aroma eines Nahrungsmittels setzt sich aus einer Vielzahl chemischer, flüchtiger Verbindungen, den Aromastoffen, die zum charakteristischen Geruch und Geschmack eines Lebensmittels beitragen, zusammen [4]. Diese Komponenten können ihren Ursprung aufgrund von biologischen und enzymatischen Prozes- 14 Keywords: sen schon im Rohmaterial haben, können aber auch aus enzymatischen, mikrobiologischen, thermischen oder chemischen Vorgängen bei Herstellungsprozessen oder der Lagerung resultieren. Die Ergebnisse der Analysen sind neben den charakteristischen Eigenschaften des zu untersuchenden Lebensmittels auch von der Analysenmethode und deren Leistung abhängig. Daher ist eine sorgfältige Auswahl einer repräsentativen Probe und der idealen Methode von größter Bedeutung. Bis heute wurde das Aromaprofil von vielen Lebensmitteln untersucht und als Ergebnis wurden tausende flüchtige Stoffe, die in unterschiedlichen Zusammensetzungen das Aroma eines Lebensmittels bestimmen, dokumentiert [5]. Ziel der durchgeführten Literaturrecherche war es, die bisher auf dem Gebiet der Aromastoffe publizierten wissenschaftlichen Studien, ausgehend von nicht aromatisierten Lebensmitteln, die im alltäglichen Verzehr vorkommen (Obst und Obstsäfte, Gemüse, Milch- und Milchprodukte, Getreideprodukte), zu erfassen. ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 So wurden zu einem Lebensmittel durchgeführte Studien und deren Ergebnisse gegenübergestellt, um Unterschiede und Gemeinsamkeiten in Bezug auf enthaltene Aromastoffe zu erkennen. Auf Grundlage dieser Erkenntnisse können auch die in unterschiedlichen Produkten einer Lebensmittelgruppe enthaltenen Aromastoffe verglichen werden, um so vor allem jene Substanzen zu erkennen, die für die Besonderheiten des Aromas eines Lebensmittels von Bedeutung sowie für die Differenzen zwischen den Aromen der einzelnen Lebensmittel entscheidend sind. 2. Aromastoffe in alltäglichen Lebensmitteln 2.1. Obst Ein wichtiges Merkmal verschiedener Obstsorten wie Kern-, Stein- und Beerenobst sowie Wild-, Zitrus- und Südfrüchte ist ein charakteristisches Aroma, welches sich im Allgemeinen erst in der Reifephase bildet [4, 6]. Die Konzentration des Gesamtaromas variiert ebenso wie die Zusammensetzung der Fruchtaromen je nach Sorte, Klima, Lage, Reifegrad, Erntezeitpunkt und Lagerbedingungen [7-16]. Aromaveränderungen können insbesondere auch bei der Zerstörung des Zellverbandes eintreten, wenn durch enzymatische Hydrolyse- oder Oxidationsvorgänge Aromastoffe gebildet werden [4]. 2.1.1. Kernobst Anhand des Vergleichs der Kernobstsorten Äpfel und Birnen ist ersichtlich, dass in beiden Früchten Hexanal, Butylacetat, Hexylacetat sowie Ethylbutanoat wesentlich zum Aroma beitragen [9, 13, 18]. Hexanol, 2-Methylbutylacetat, Ethyl-2-methylbutanoat, 3-Methylbutylhexanoat, Hexylbutanoat, Hexylhexanoat sowie ß-Damascenon [9, 10, 17] werden hingegen nur als für das Apfelaroma charakteristisch erachtet, während Methyl-2,4-decadienoat, Ethyl-2,4-decadienoat und 1,3-Dihydroxypropanon für Birnenaroma kennzeichnend sind [13, 18]. Der Erntezeitpunkt beeinflusst die Entstehung von Aromastoffen in Äpfeln: So zeigte sich bei einer Ernte vor Eintritt der Pflückreife eine verminderte und später einsetzende Synthese des Aromas [9]. Diese Erkenntnisse werden dadurch gestützt, dass es noch während des Rötungs- und Reifungsprozesses vor der Ernte der Äpfel zu einem Anstieg des Gesamtaromas kommt [11]. Zudem wurde festgestellt, dass sich flüchtige Inhaltsstoffe von nachreifenden Früchten, zu denen sowohl Äpfel als auch Birnen zählen, nach dem respiratorischen Klimakterium anreichern, ihr Gehalt während der weiteren Lagerung aber wieder abnimmt. Eine verringerte Aromastoffproduktion ist die Folge der Lagerung von Birnen unter kontrollierter Atmosphäre bei verringertem Sauerstoffgehalt sowie von Äpfeln bei Lagerung mit 1,5 % O2 und 1,5 % CO2 bei 1 °C [7]. ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 2.1.2. Steinobst Jede der Steinobstsorten Marille, Nektarine und Pfirsich beinhaltet im Reifezustand als aromawirksame Substanzen Decalacton und Linalool [19]. Marillen enthalten als charakteristische Verbindungen zudem Ethylacetat, Hexylacetat, (E)-Hexen-2-al, ß-Ionon, ß-Cyclocitral, Limonen und 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-on, Nektarinen hingegen γ-Hexalacton, γ-Octalacton sowie Terpinolen und Pfirsiche γ- und δ-Dodecalacton [12, 19, 20]. Eine Untersuchung zur Veränderung der Komposition flüchtiger Substanzen während des Wachstums und der Reifung von Nektarinen und Pfirsichen ergab ein breites Spektrum quantitativer und qualitativer Variationen. So stellen C6-Aldehyde und Alkohole, wie Hexanal, (E)-2-Hexanal, Hexanol und (E)-2-Hexenol, die Hauptkomponenten in unreifen Pfirsichen dar. Mit Ausnahme von (Z)-3-Hexenol, welches in reifen Früchten sein Konzentrationsmaximum erreicht, nimmt die Menge an Aldehyden, Alkoholen und Estern während des Wachstums ab. Lactone, vorwiegend γ- und δ-Decalactone sowie γ- und δ-Dodecalactone, nehmen hingegen zu. Auch der Gehalt an Benzaldehyd und Linalool sinkt signifikant und erreicht in reifen Früchten die höchste Konzentration. Zudem wurden bei Pfirsichen mit weißem Fruchtfleisch signifikant höhere Konzentrationen an Hexanal, (E)-2-Hexenal, Linalool, Phellandren sowie γ- und δ-Decalacton festgestellt als in Sorten mit gelbem Fruchtfleisch [12]. 2.1.3. Beerenobst Im Brombeeraroma stellen p-Cymen-8-ol und Heptanol relevante Komponenten dar, aber auch die Aldehyde Hexanal, (E)-2-Hexanal und 3-Methylbutanal sind von Bedeutung [21]. Wichtige Substanzen für das Aroma von Erdbeeren sind (Z)-3-Hexenal, Butylacetat, Methyl- und Ethylbutanoat, Methyl- und Ethylhexanoat sowie Furaneol [22, 23, 24, 25]. Zudem wurden Methylcinnamat, Linalool, Methylhexanoat, Octylbutanoat und Nerolidol identifiziert [24, 26, 27]. Zum Himbeeraroma hingegen trägt 4-(4-Hydroxyphenyl)-butan-2-on, das Himbeerketon, erheblich bei, aber auch Ethylheptanoat und die Terpene α- und βIonon, α-Pinen, Citral, Terpinolen sowie Caryophyllen sind wesentlich [6, 28]. In Bezug auf die Lagertemperatur wurde festgestellt, dass Erdbeeren, die bei einer Temperatur von 5 °C oder 10 °C gelagert wurden, einen höheren Gehalt der identifizierten Aromakomponenten und eine verbesserte antioxidative Kapazität aufwiesen als jene Früchte, die bei 0 °C gelagert wurden [29]. 2.1.4. Zitrusfrüchte Schalenöle von Orangen enthalten in etwa 90 % Monoterpene, von denen rund 60 bis 95 % auf Limonen entfallen. Die Aromastoffe des Fruchtfleisches bestehen ebenfalls zu einem beträchtlichen Teil aus 15 Terpenkohlenwasserstoffen, wobei gegenüber den Schalenölen der Anteil an Alkoholen, Aldehyden und Estern erheblich höher ist. Aufgrund der Gehalte und Schwellenwerte dürften Limonen, Linalool und Ethylbutanoat für das Aroma von Orangen ausschlaggebend sein. Des Weiteren wurden Citral, Myrcen, Sabinen, Valencen, α-Terpineol, α-Pinen, Decanal, Nonanal, Octanal, Ethylacetat sowie Ethyl-3-hydroxyhexanoat als Substanzen beschrieben, die für das Aroma einen wichtigen Beitrag leisten [6, 30, 31]. 2.1.5. Südfrüchte Unter den Südfrüchten können bei Ananas Methylund Ethyl-3-(Methylthio)-Propanoat, Methylbutanoat, Methylhexanoat, Ethylhexanoat sowie Mesifuran und Furaneol als Schlüsselsubstanzen genannt werden [1, 32]. Amyl- und Isoamylester der Essig-, Propion- und Buttersäure sowie Eugenol, Methyleugenol und Elemicin sind für das charakteristische Bananenaroma von Bedeutung [33, 34]. Zur Bestimmung der aromatischen Komponenten während der Reifung wurden anhand der Schalenfarbe Bananen aus unterschiedlichen Anbaugebieten, die sich im selben Reifestadium befanden, ausgewählt. Im Zuge der Untersuchung wurde erkannt, dass Ester einen wichtigen Teil der flüchtigen Inhaltsstoffe von frischen Bananen darstellt und Isoamylacetat konnte als character impact compound des Aromas beschrieben werden. Bananen mit dem Schalenfarbindex 3 auf der Chiquita® Farbanzeige wurden während einer siebentägigen Lagerung bei Raumtemperatur analysiert. Zu Beginn der Lagerung wurden nur Isoamylacetat, Butylacetat und Elemicin identifiziert, während der Lagerung jedoch stieg der Gehalt der Aromakomponenten an [34]. Die Hauptkomponenten des Mango-Aromas sind αTerpinolen, δ-3-Caren, Myrcen, α-Pinen, Limonen, Linalool, ß-Selinen und ß-Caryophyllen sowie Ethylhexanoat und Ethyloctanoat [35, 36]. Zudem wurden auch die Sesquiterpene Allo-Aromadendren, α-Gurjunen sowie ß-Gurjunen identifiziert [16, 35]. 2.2. Obstsäfte Der Vergleich der bedeutendsten aromawirksamen Substanzen in Äpfeln und Apfelsaft zeigt in beiden Lebensmitteln das Vorkommen von Hexanol, Hexanal, Butyl-, Pentyl- und Hexylacetat sowie Ethylbutanoat [8, 10, 46, 47]. In aus Jonagold Äpfeln hergestelltem Saft wurde die Zusammensetzung der flüchtigen Substanzen gleich nach dem Pressen und im Verlauf bis zu sechs Stunden danach untersucht und es wurde festgestellt, dass der frische, fruchtige und apfelartige Geruch in den ersten beiden Stunden der Bräunung zu-, danach aber abnahm. Der süße Geruch des Saftes hingegen nahm während der ersten Stunde der Bräunung stark zu und blieb danach auf diesem Niveau. Diese Veränderungen des Geruchs gehen mit der Abnahme von 16 (E)-2-Hexenal und der Zunahme der Acetatester einher, welche somit zum Aroma und zum Geruch des Apfelsaftes beitragen [48]. Sowohl im Aroma von Birnensaft als auch in jenem von Birnen wurden Hexylacetat und Ethyl-2,4-(E,Z)decadienoat gefunden [13, 18, 49]. In zehn von elf untersuchten Birnensäften wurde zudem α-(E,E)-Farnesen nachgewiesen, in neun 1-Hexanol, Ethyloctanoat, Ethyldecanoat und Cinnamaldehyd. Methyl-2,4-(E,Z)decadienoat und Ethyl-2,4-(E,E)-decadienoat wurden in acht Proben detektiert [49]. Marillensaft beinhaltet, wie auch die Ausgangsfrucht, γ-Decalacton, ß-Ionon und Linalool [19]. Zudem kann Limonen als für das Aroma ausschlaggebende Substanz beschrieben werden und in einigen Säften wurden auch 1-Hexanol, Hexylisovalerat, α-Terpinolen, α-Terpineol, α(Z,E)-Farnesen und Cinnamaldehyd sowie für das Marillenaroma wichtige Ethyl- und Hexylester nachgewiesen. Als Aromastoffe in Pfirsichsaft sind, wie auch in Pfirsichen, γ-Decalacton und Linalool wesentlich. Auch Cinnamaldehyd, α-Terpineol, Linalool und Limonen sowie α-(E,E)-Farnesen und Ethyloctanoat konnten nachgewiesen werden [49]. Sowohl in Orangen als auch in Orangensaft ist Limonen der mengenmäßig wichtigste Aromastoff [50], nicht jedoch der bedeutendste für die Qualität des Aromas. Ferner sind Citral, Linalool, α-Pinen, Acetaldehyd, Octanal und Ethylbutanoat wichtige Komponenten [51–53]. Ebenso tragen 2-Methylbutanoat [51], Hexanal, Decanal [52], 4-Terpineol, Octanol, Sabinen, Myrcen und Valencen [51, 53, 54] wesentlich zum Aroma bei. 2.3. Gemüse Gemüse kann in Frucht-, Wurzel- und Knollengemüse, Blatt- und Stielgemüse sowie Leguminosen, Zwiebelgewächse und Kohlgemüse eingeteilt werden [6]. Die Vielzahl der Gemüsesorten bedingt eine große Vielfalt an Aromastoffen, die sich im Allgemeinen erst in der Reifephase bilden [4, 6]. Auch wenn die Gemüse zur selben Art zählen und eine ähnliche chemische Zusammensetzung aufweisen, so unterscheiden sie sich dennoch im Aroma deutlich. Ebenso variieren die Konzentrationen des Gesamtaromas je nach Sorte, Klima, Lage, Reifegrad, Erntezeitpunkt und Lagerbedingungen [37–40]. Aromaveränderungen können insbesondere auch bei der Zerstörung des Zellverbandes eintreten, wie dies bei der Zwiebel der Fall ist [1, 4, 6, 41]. 2.3.1. Fruchtgemüse Gurken, die wie Paprika und Tomaten zu den Fruchtgemüsen zählen, enthalten als eine für das Gurkenaroma wichtigste Komponente (E,E)-2,4-Nonadienal [42]. Als aromaintensivster Stoff zerkleinerter Gurken wurde (E,Z)-2,6-Nonadienal, gefolgt von (Z)-2-Nonenal und (E)-2-Nonenal identifiziert [41]. Zudem wur- ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 den Alkohole und Aldehyde mit neun Kohlenstoffatomen, wie Nonanol, (E)-2-Nonen-1-ol, (Z)-6-Nonen1-ol, (E,Z)-2,6-Nonadien-1-ol, (Z,Z)-3,6-Nonadien-1-ol, Nonanal, (Z)-3-Nonenal, (Z)-6-Nonenal und (Z,Z)-3,6Nonadienal als wichtige aromawirksame Substanzen beschrieben [6]. Im Aroma des Gemüsepaprikas steht ß-Ocimen mengenmäßig stark im Vordergrund, aber auch (E,Z)-2,6Nonadienal, das ebenso in Gurken vorkommt, (Z)3-Hexenol, 2-Hexenal, 2-Nonen-4-on, Linalool und 3-Isobutyl-2-methoxypyrazin sind wichtige aromawirksame Substanzen [6, 37]. Zudem wurde beobachtet, dass die Konzentrationen an ß-Ocimen und (Z)3-Hexenol beim Übergang der Paprikafarbe von grün auf rot stark abnahmen, während mit 2-Hexenal und (E)-2-Hexenol die fruchtig-süßen und frischen Aromanoten des roten Gemüsepaprikas anstiegen [37]. Das Aroma der Tomaten wird vor allem durch Hexanal, Hexenal, (Z)-3-Hexenal, (E)-2-Hexenal, (E)-2-Heptenal, Methional, 3-Methylbutanal, (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal, 3-Methylbutanol, 1-Octen-3-on, 1-Penten-3-on, 6-Methyl-5-hepten-2-on, 2-Isobutylthiazol und 2-Isobutylionon bestimmt [39, 44]. In frischen, reifen Tomaten wurden nur wenige Terpenoide detektiert, darunter Limonen [44]. Untersuchte Tomaten, die schon tafelreif geerntet wurden, wiesen höhere Intensitäten des fruchtig-blumigen Aromas auf, als diejenigen, die schon früher eingebracht wurden. Auch der Gehalt an flüchtigen Substanzen von tafelreif geernteten Tomaten war stets höher als jener von grün geernteten Tomaten, die daraufhin noch unter unterschiedlichen Bedingungen gelagert wurden [38]. Um die Veränderungen des Geruchs und der beinhalteten Aromastoffe von Tomaten während der Lagerung zu analysieren, wurden drei unterschiedliche Sorten rot und reif geerntet und in einem Klimaraum bei freier Konvektion, 20 °C, einer relativen Luftfeuchtigkeit von 55 % und einer Luftgeschwindigkeit von < 0,1ms-1 gelagert, um die Gegebenheiten eines Haushalts zu simulieren. In allen drei Sorten nahm die Intensität des Attributs „tomatenartig“ während der Lagerung zu, aber auch jene des unerwünschten Attributs „modrig“ stieg an. Es stellte sich heraus, dass Hexanal und 2-Isobutylthiazol mit dem Attribut „modrig“ in Verbindung standen. Das Vorkommen der flüchtigen Aromakomponenten 3-Methylbutanal, 6-Methyl-5-Hepten-2-on, (E)-2-Heptenal, (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal und Geranylaceton korrelierte positiv mit dem „tomatenartigen“ Aroma [39]. 2.3.2. Wurzelgemüse Karotten, die zu den Wurzelgemüsen zählen, weisen ein typisches Aroma auf, das zu 97 % auf Terpene und Sesquiterpene, wie α-Pinen, Sabinen, Myrcen, Limonen, γ-Terpinen, Terpinolen, ß-Caryophyllen und γ-Bisabolen, zurückzuführen ist. Zwischen den einzel- ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 nen Sorten bestehen weniger qualitative als quantitative Unterschiede [6, 40]. So wurden sowohl Myrcen, ß-Caryophyllen, γ-Bisabolen als auch Sabinen als Hauptverbindungen unterschiedlicher Sorten identifiziert. Sabinen und teilweise auch Myrcen wurden mit dem „erdigen“ Aroma von Karotten in Verbindung gebracht. Während der 28-tägigen Lagerung bei 5, 25 und 35 °C veränderte sich die Zusammensetzung der Karotten nicht wesentlich, mit Ausnahme von Propanol, welches bei höher werdenden Temperaturen aufgrund von sich ausbreitenden Fäulnisbakterien exponentiell anstieg. Nach einer Kochzeit der Karotten von 10, 20 und 30 Minuten, konnten Verluste der flüchtigen Substanzen von 88,0 %, 93,0 % und 95,5 % festgestellt werden. Hierbei sind Sesquiterpene dem Kochprozess gegenüber beständiger als Monoterpene [40]. 2.3.3. Zwiebelgewächse Bei der Zerstörung des Zellgewebes der Zwiebel, wie beim Zerkleinern, entsteht 3-Mercapto-2-methylpentan-1-ol, das zusammen mit 1-Propanthiol, Dimethyldisulfid, 2,5-Dimethylthiophen und 2-Propenylpropyldisulfid sowie einigen Alkylthiosulfinaten für das Aroma von rohen Zwiebeln von großer Bedeutung ist [1, 41]. Zudem wird durch Alliinase aus S-1-PropenylL-cystein-sulfoxid die tränenreizende Substanz Propanthial-S-oxid gebildet [45], die auch den typischen Geruch der Zwiebel ausmacht [6]. In Bezug auf die vorkommenden Thiosulfinate stehen 1-Propenylmethan- und 1-Propenylpropanthiosulfat sowie Methyl- und Propyl-(E)-1-propenthiosulfat mengenmäßig im Vordergrund. Neben den angeführten Thiosulfinaten gibt es noch weitere zu diesen Verbindungen zählende Substanzen, die als Zwiebelane bezeichnet werden [6]. 2.4. Milchprodukte 2.4.1. Milch Zum Aroma von roher oder schonend, bei 73 °C 12 sec. pasteurisierter Milch tragen vor allem Dimethylsulfid, Diacetyl, 2-Methylbutanol, (Z)-4-Heptenal, (E)-2-Nonenal und 3-Butenylisothiocyanat bei. Aber auch Hexanal, Heptanal und Ethylbutanoat sind vorhanden. In ultrahocherhitzter Milch hingegen ist δ-Decalacton der dominierende Aromastoff, zudem leisten auch 2-Acetyl-1-pyrrolin, Methional, 2-Acetylthiaozolin und 4,5-Epoxy-2-decenal einen Beitrag [1,55]. Bei Milch und Milchprodukten kann das Aromaprofil des Lebensmittels auch durch Produktionsbedingungen, Verpackungsmaterial und Lagerung beeinflusst werden [1, 56]. 2.4.2. Butter Für das typische Aroma von Butter guter Qualität spielt einerseits das Rohmaterial und andererseits auch die metabolische Aktivität der Starterbakterien, wie bei 17 Sauerrahmbutter, eine wichtige Rolle [56]. Diacetyl, δ-Decalacton und Butansäure sind die Schlüsselaromastoffe in Butter [1, 57]. Untersuchungen verschiedener Autoren zeigten, dass auch das Vorhandensein von kurzkettigen Fettsäuren, Aldehyden, Ketonen, Alkoholen, Estern, Lactonen, Terpenen und schwefelhaltigen Komponenten für das Aroma von Butter eine wichtige Rolle spielt [56]. 2.4.3. Joghurt Für das Joghurtaroma von großer Bedeutung sind Stoffwechselprodukte jener Bakterienkulturen, die zur homogenisierten und pasteurisierten Milch zugegeben werden. Zur Fermentation werden oftmals Milchsäurebakterien verwendet, durch die Diacetyl, Ethanal, Dimethylsulfid, Essigsäure und Milchsäure entstehen [1, 58, 59]. Als aromagebende Substanzen wurden auch Acetaldehyd, 2-Butanon und Acetoin detektiert [58, 59]. 2.4.4. Käse Gereifte Käsesorten, die vorerst aus einer geschmacksneutralen Käsemasse bestehen, erhalten durch enzymatische Umsetzungen das charakteristische Aroma [60–62]. Zu den Hartkäsen gehörend, zählen in Grana Parmigiano Reggiano Butter-, Essig- und Hexansäure sowie Ethylhexanoat, Ethylbutanoat und Ethyloctanoat zu den im Aroma überwiegend vorkommenden Stoffen. Auch in Grana Padano wurden Ethylbutanoat und Ethylhexanoat als für das Aroma ausschlaggebende Substanzen beschrieben [63]. Im Vergleich mit Grana Padano und Grana Parmigiano Reggiano wurden in Pecorino die höchsten Mengen an Butan- und Hexansäure nachgewiesen, während Ethylhexanoat mittels Olfaktometrie als impact compound des Grana Padano genannt wurde. In Parmesan und Pecorino waren Trimethyl- und Tetramethylpyrazin in allen untersuchten Aromaprofilen präsent, in Parmesan wurde zudem auch δ-Decalacton nachgewiesen [64]. Die höchsten Aromawerte in Emmentaler wurden für Methional, Furaneol und Mesifuran dargelegt, aber auch Ethylhexanoat, Ethylbutanoat, Diacetyl, 3-Methylbutanal, Buttersäure und Propionsäure sind von großer Relevanz [1, 65, 66]. Für die buttrige Note des Goudas, eines Schnittkäses, sind δ-Decalacton, δ-Dodecalacton, γ-Dodecalacton und Acetoin verantwortlich [62, 67, 66]. Zudem stellen 2-Methylketone wichtige Aromastoffe für Gouda und Cheddar dar [62]. In Letzterem wurden auch δ-Decalacton, Diacetyl, Methional, Methanthiol, Dimethyldisulfid, Dimethyltrisulfid und Buttersäure nachgewiesen [64, 68]. In Blauschimmelkäse, einem halbweichen Schnittkäse, wurden p-Kresol und 1-Phenylethylalkohol als character impact compounds beschrieben und Methanthiol, Methional sowie Dimethyltrisulfid als wichtige Substanzen genannt [64]. 18 Camembert, ein Weichkäse, beinhaltet Phenylacetaldehyd, 2-Phenylethanol und Phenethylacetat als aromagebende Komponenten. Zudem wurden Buttersäure, Diacetyl, 3-Methylbutanal und γ-Decalacton als bedeutend beschrieben [69]. Das Aromaprofil von ungereiftem Käse, wie Mozzarella, besteht aus butterartigen, süßlichen, salzigen und sauren Noten, die vorwiegend von Diacetyl, δ-Decalacton, Natriumchlorid und Milchsäure verursacht werden [1]. 2.5. Getreideprodukte Während der Herstellung ist neben dem Backprozess, der das typische Aroma von Brot wesentlich bestimmt, auch die Sauerteigfermentation ein wichtiger Schritt in der Entwicklung des Aromas. So spielen bei der Fermentation neben den verwendeten Starterkulturen auch die Herstellungsparameter wie Temperatur, Zeit und pH-Wert eine Rolle [70, 71]. Der Vergleich von in Weizenbrotkruste und Weizenbrotkrume enthaltenen Aromastoffen zeigt das Auftreten von 3-Methylbutanal und (E)-2-Nonenal in beiden Proben [1, 72]. Sowohl in Weizen- als auch in Roggenbrotkruste kommen 2-Acetyl-1-pyrrolin, 3-Methylbutanal und (E)-2-Nonenal vor [1, 70, 71]. Wie in Weizenbrotkrume wurden auch in jener von Roggensauerteigbrot 3-Methylbutanal, (E)-2-Nonenal und (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal detektiert. Roggenmehl und Roggensauerteig enthalten nachweislich Methional, Hexanal, Sotolon und (E)-4,5Epoxy-(E)-2-decenal. In der Krume des Roggensauerteigbrots sind ebenso wie im Mehl dieses Getreides Hexanal, Sotolon, (E,E)-2,4-Decadienal und (E)-2-Nonenal enthalten [72]. Schlussfolgerung Jedes Lebensmittel weist ein charakteristisches Aroma auf, das sich aus einer Vielzahl an Aromastoffen in unterschiedlichen Konzentrationen zusammensetzt. In der vorliegenden Arbeit zeigt der Vergleich vieler Studien zu Obst und Gemüse einen Einfluss der Wachstumsbedingungen, des Erntezeitpunkts, des Reifegrads bei der Ernte und der Lagerbedingungen auf das Aromaprofil. Auch durch Verarbeitung, wie im Falle der Zwiebel, kann die Zusammensetzung des Aromas verändert werden. Bei Milch und Milchprodukten können zudem Produktionsbedingungen und Verpackungsmaterial das Aromaprofil des Lebensmittels beeinflussen. Beim Aroma der Getreideprodukte sind neben den Herstellungsparametern wie Temperatur, Zeit und pH-Wert auch die bei der Fermentation verwendeten Starterkulturen von Bedeutung. Die Ergebnisse des Aromaprofils sind von den charakteristischen Eigenschaften des zu untersuchenden Lebensmittels, der Analysenmethode und deren Dis- ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 positionen abhängig. Daher ist eine sorgfältige Auswahl einer repräsentativen Probe und der idealen Methode sehr wichtig. Da manche Lebensmittel Thema von einer Vielzahl an Studien sind, andere hingegen bisher weniger umfassend analysiert wurden, ergibt sich in manchen Bereichen ein noch durchaus großer Forschungsbedarf. Literatur [01] Belitz H.D., Grosch W., Schieberle P.: Lehrbuch der Lebensmittelchemie, 6. Auflage, Springer Verlag Berlin-Heidelberg, 2008, 557–561, 757–761, 796–797, 813–816, 832–833, 863–867. [02] Schreier P.: Aromaforschung aktuell. In: Naturwissenschaften (Autrum H., Hrsg.). Springer Verlag Berlin-Heidelberg, 1995, 82: 21–27. [03] DIN 10950-1:1999-04. Deutsches Institut für Normung e.V. Sensorische Prüfung, Beuth Verlag Berlin. [04] Eisenbrand G, Schreier P.: Römpp Lexikon Lebensmittelchemie, Georg Thieme Verlag Stuttgart-New York, 2006; 71–77, 392–394. [05] Plutowska B., Wardencki W.: Aromagrams – Aromatic profiles in the appreciation of food quality. Food Chem 2007; 101: 845–872. [06] Herrmann K.: Inhaltsstoffe von Obst und Gemüse, Ulmer Verlag Stuttgart, 2001; 6–7, 12, 29–30, 38–39, 68, 83, 85, 105–106, 157–158. [07] Girard B., Lau O.L.: Effect of maturity and storage on quality and volatile production of “Jonagold” apples. Food Res Int 1995; 28: 465–471. [08] Xiaobo Z., Jiewen Z.: Comperative analysis of apple aroma by a tin-oxide gas sensor array device and GC/MS. Food Chem 2008; 107: 120–128. [09] Song J., Bangerth F.: The effect of harvest date on aroma compound production from “Golden Delicious” apple fruit and relationship to respiration and ethylene production. Postharvest Biol Technol 1996; 8: 259–269. [10] Vanoli M., Visai C., Rizzolo A.: The influence of harvest date on the volatile composition of “Starkspur Golden” apples. Postharvest Biol Techno 1995; 6: 225–234. [11] Lo Scalzo R., Testoni A., Genna A.: “Annurca” apple fruit, a southern Italy apple cultivar: textural properties and aroma composition. Food Chem 2001; 73: 333–343. [12] Vanoli M., Visai C.: Volatile compound production during growth and ripening of peaches and nectarines. Scientia Horticulturae 1997; 70: 15–24. [13] Chen J.L., Yan S., Feng Z., Xiao L., Hu X.S.: Changes in the volatile compounds and chemical and physical properties of Yali pear (Pyrus bertschneideri Reld) during storage. Food Chem 2006; 97: 248–255. [14] Lara I., Miró R.M., Fuentes T., Sayez G., Graell J., López M.L.: Biosynthesis of volatile aroma com- ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 pounds in pear fruit stored under long-term controlled atmosphere condition. Postharvest Biol Technol 2003; 29: 29–39. [15] Chervin C., Speirs J., Loveys B., Patterson B.D.: Influence of low oxygen storage on aroma compounds of whole pears and crushed pear flesh. Postharvest Biol Technol 2000; 19: 279–285. [16] Lalel H.J.D., Singh Z., Chye Tan S.: Aroma volatiles production during fruit ripening of “Kensington Pride” mango. Postharvest Biol and Technol 2003; 27: 323–336. [17] Villatoro C., Altisent R., Echeverría G., Graell J., López M.L., Lara I.: Changes in biosynthesis of aroma compounds during on-tree maturation of “Pink Lady” apples. Postharvest Biol Technol 2008; 47: 286–295. [18] Diban N., Ruiz G., Urtiaga A., Ortiz I.: Granula activated carbon for the recovery of the main pear aroma compound: Viability and kinety modelling of ethyl-2,4-decadienoate adsorption. J Food Engineering 2007; 78: 1259–1266. [19] Guillot S., Peytavi L., Bureau S., Boulanger R., Lepoutre J.-P., Crouzet J., Schorr-Galindo S.: Aroma characterisation of various apricot varieties using headspace-solid phase microextraction combined with gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and gas chromatography-olfactometry. Food Chem 2006; 96: 147–155. [20] Aubert C., Baumann S., Arguel H.: Optimization of the analysis of flavor volatile compounds by Liquid-Liquid Microextraktion (LLME). Application to the aroma analysis of melons, peaches, grapes, strawberries and tomatoes. J Agric Food Chem 2005; 53: 8881–8895. [21] Ibáñez E., López-Sebastián S., Ramos S., Tabera J., Reglero G.: Analysis of volatile fruit components by headspace solid-phase microextraction. Food Chem 1998; 63: 281–286. [22] Pelayo C., Ebeler S.E., Kader A.A.: Postharvest life and flavor quality of three strawberry cultivars kept at 5°C in air or air+20 kPa CO2. Postharvest Biol Technol 2003; 27: 171–183. [23] Larsen M., Poll L., Olsen C.E.: Evaluation of the aroma composition of some strawberry (Fragraria ananassa Duch) cultivars by use of odour threshold values. Z Lebensmittelunters -forschung 1992; 195: 536–539. [24] Williams A., Ryan D., Guasca A.O., Marriott P., Pang E.: Analysis of strawberry volatiles using comprehensive two-dimensional gas chromatography with headspace solid-phase microextraction. J Chrom 2005; 817: 97–107. [25] Schieberle P., Hofmann T.: Evaluation of the character impact odorants in fresh strawberry juice by quantitative measurements and sensory studies on model mixtures. J Agric Food Chem 1997; 45: 227–232. 19 [26] Kyriacou A., Zabetakis I.: The biosynthesis of furanones in strawberry: Are the plant cells all alone? In: Food Flavor and Chemistry (Spanier A.M., Shahidi F., Parliment T.H., Mussinan C., Ho C.-T., Tratras Contis E., Hrsg). The Royal Soc Chem Cambridge, 2005; 219. [27] Ingham K.E., Linforth R.S.T., Taylor A.J.: The effect of eating on aroma release from strawberries. Food Chem 1995; 54: 283–288. [28] Shamaila M., Skura B., Daubeny H., Anderson A.: Sensory, chemical and gas chromatographic evaluation of five raspberry cultivars. Food Res Int 1993; 26: 443–449. [29] Ayala-Zavala J.F., Wang S.Y., Wang C.Y., González-Aguilar A.: Effect of storage temperatures on antioxidant capacity and aroma compounds in strawberry fruit. Lebensmittel-Wiss u-Technol 2004; 37: 687–695. [30] Moshonas M.G., Shaw P.E.: Fresh orange juice flavor: A quantitative and qualitative determination of the volatile constituents. Developments in Food Sci 1995; 37: 1479–1492. [31] Moufida S., Marzouk B.: Biochemical characterization of blood orange, sweet orange, lemon, bergamot and bitter orange. Phytochem 2003; 62: 1284–1289. [32] Elss S., Preston C., Hertzig C., Heckel F., Richling E., Schreier P.: Aroma profiles of pineapple fruit (Ananas comosus [L.] Merr.) and pineapple products. Lebensmittel-Wiss u- Technol 2005; 38: 263–274. [33] Meng L.I., Slaughter D.C., Thompson J.E.: Optical chlorophyll sensing system for banana ripening. Postharvest Biol Technol 1997; 12: 273–283. [34] Boudhrioua N., Giampaoli P., Bonazzi C.: Changes in aromatic components of banana during ripening and air-drying. Lebensmittel-Wiss u -Technol 2003; 36: 633–642. [35] Andrade E.H.A., Maia J.G.S., Zoghbi M.B.: Aroma volatile constituents of brazilian varieties of mango fruit. J Food Comp Anal 2000; 13: 27–33. [36] Koulibaly A., Sakho M., Crouzet J.: Variability of free and bound volatile terpenic compounds in Mango. Lebensmittel-Wiss und Technol 1992; 4: 374–379. [37] Mateo J., Aguirrezábal M., Domínguez C., Zumalacárregui J.M.: Volatile compounds in Spanish paprika. J Food Comp Anal 1997; 10: 225–232. [38] Stern D.J., Buttery R.G., Teranishi R., Ling L.: Effect of storage and ripening on fresh tomato quality. Food Chemistry 1994; 49: 225–231. [39] Krumbein A., Peters P., Brückner B.: Flavour compounds and a quantitative descriptive analysis of tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) of different cultivars in short-term storage. Postharvest Biology Technol 2004; 32: 15–28. [40] Alasalvar C., Grigor J.M., Quantic P.C.: Method for 20 the static headspace analysis of carrot volatiles. Food Chem 1999; 65: 391–397. [41] Zhang Z.-M., Li G.-K.: A preliminary study of plant aroma profile characteristics by combination sampling method coupled with GC-MS. Microchem J 2007; 86: 29–36. [42] Kohl D., Heinert L., Bock J., Hofmann T., Schieberle P.: Systematic studies on responses of metaloxide sensor surfaces to straight chain alkanes, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, acids and esters using the SOMMSA approach. Sensors and Actuators 2000; 70: 43–50. [43] Schieberle P., Ofner S., Grosch W.: Evaluation of potent odorants in cucumbers (Cucumis sativus) and muskmelons (Cucumis melo) by aroma extract dilution analysis. J Food Sci 1990; 55: 193– 195. [44] Berna A.Z., Lammertyn J., Buysens S., Di Natale C., Nicolai B.M.: Mapping consumer liking of tomatoes with fast aroma profiling techniques. Postharvest Biol Technol 2005; 38: 115–127. [45] Mondy N., Duplat D., Christides J.P., Arnault I., Auge J.: Aroma analysis of fresh and preserved onions and leek by dual solid-phase microextraction – liquid extraction and gas chromatography – mass spectrometry. J Chrom A 2002; 963: 89–93. [46] Fricker A.: Lebensmittel – mit allen Sinnen prüfen! Springer Verlag Berlin-Heidelberg, 1984; 56, 59, 70. [47] Sancho M.F., Rao M.A., Downing D.L.: Infinite dilution activity coefficients of apple juice aroma compounds. J Food Eng 1997; 34: 145–158. [48] Komthong P., Katoh T., Igura N., Shimoda M.: Changes in the odours of apple juice during enzymatic browning. Food Qual Pref 2006; 17: 497–504. [49] Riu-Aumatell M., Castellari M., López-Tamames E., Galassi S., Buxaders S.: Characterisation of volatile compounds of fruit juices and nectars by HS/SPME and GC/MS. Food Chem 2004; 87: 627– 637. [50] Elss S., Kleinhenz S., Schreier P.: Odor and taste thresholds of potential carry-over/off-flavor compounds in orange and apple juice. LebensmittelWiss Technol 2007; 40: 1826–1831. [51] Jia M., Zhang H., Min D.B.: Pulsed electric field processing effects on flavour compounds and microorganisms of orange juice. Food Chem 1999; 65: 445–451. [52] Jordán M.J., Goodner K.L., Laencina J.: Deaeration and pasteurization effects of the orange juice aromatic fraction. Lebensmittel-Wiss-Technol 2003; 36: 391–396. [53] Shaw P.E., Rouse R.L., Goodner K.L., Bazemore R., Nordby H.E., Widmer W.W.: Comparison of Headspace GC and Electronic Sensor Techniques for classification of processed orange juices. Lebensmittel-Wiss-Technol 2000; 33: 331–334. ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 [54] Tønder D., Petersen M.A., Poll L., Olsen C.E.: Discrimination between freshly made and stored reconstituted orange juice using GC odour profiling and aroma values. Food Chem 1998; 61: 223–229. [55] Bendall J.G., Olney S.D.: Hept-cis-4-enal: analysis and flavour contribution to fresh milk. Int. Dairy J 2001; 11: 855–864. [56] Povolo M., Contarini G.: Comparison of solidphase microextraction and purge-and-trap methods for the analysis of the volatile fraction of butter. J. Chrom A 2003; 985: 117–125. [57] Schieberle P., Gassenmeier K., Guth H., Sen A., Grosch W.: Character impact odour compounds of different kinds of butter. Lebensmittel-WissTechnol 1993; 26: 347–356. [58] Gardini F., Lanciotti R., Guerzoni M.E., Torriani S.: Evaluation of aroma production and survival of Streptococcus termophilus, Lactobacillus delbrueckii subsp. bulgaricus and Lactobacillus acidophilus in fermented milks. Int Dairy J 1999. 9: 125–134. [59] Görner F.: Aroma von Sauermilchprodukten. Food 2006; 24: 63–69. [60] Marilleya L., Ampueroa S., Zesigerb T., Caseya M.G.: Screening of aroma-producing lactic acid bacteria with an electronic nose. Int Dairy J 2004; 14: 849–856. [61] Pionnier E., Engel E., Salles C., Le Quéré J.L.: Interactions between non-volatile water-soluble molecules and aroma compounds in Camembert cheese. Food Chem 2002; 76: 13–20. [62] Van Leuven I., Van Caelenberg T., Dirinck P.: Aroma characterisation of Gouda-type cheeses. Int Dairy J 2008; 18: 790–800. [63] Moio L., Addeo F.: Grana Padano cheese aroma. J Dairy Res 1998; 65: 317–333. [64] Frank D.C., Owen C.M., Patterson J.: Solid phase microextraction (SPME) combined with gas-chromatography and olfactometry-mass spectrometry for characterization of cheese aroma compounds. Lebensmittel-Wiss-Technol 2004; 37: 139–154. [65] Preininger M., Grosch W.: Evaluation of key odorants of the neutral volatiles of Emmentaler cheese by the calculation of odour activity values. Lebensmittel-Wiss-Technol 1994; 27: 237–244. [66] Yvon M., Rijnen L.: Cheese flavour formation by amino acid catabolism. Int Dairy J 2001; 11: 185– 201. [67] Dirinck P., De Winne A.: Flavour characterisation and classification of cheeses by gas chromatographic-mass sprectrometric profiling. J Chrom A 1999; 847: 203–208. [68] O’riordan P.J., Delahunty C.M.: Characterisation of commercial Cheddar cheese flavour. 2: study of Cheddar discrimination by composition, volatile compounds and descriptive flavour assessment. Int Dairy J 2003; 13: 371–389. ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 [69] Kubícková J., Grosch W.: Evaluation of flavour compounds of Camembert cheese. Int. Dairy J, 1998; 8: 11–16. [70] Schieberle P., Grosch W.: Evaluation of the flavour of wheat and rye bread crusts by aroma extract dilution analysis. Z. Lebensmittelunters – Forsch A 1987; 185: 111–113. [71] Schieberle P., Grosch W.: Quantification of aroma compounds in wheat and rye bread crusts using a stable isotope dilution assay. J. Agriculture and Food Chemistry 1987b; 35: 252–257. [72] Hansen A., Schieberle P.: Generation of aroma compounds during sourdough fermentation: applied and fundamental aspects. Trends Food Sci & Technol 2005; 16: 85–94. Adresse der Autoren: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Dorota Majchrzak* Kathrin Eisinger Universität Wien Institut für Ernährungswissenschaften Althanstraße 14, 1090 Wien t +43 1 4277 54948 f + 43 1 4277 9549 [email protected] * korrespondierende Autorin Helfen Sie den Kindern, werden Sie SOS-Kinderdorf-Pate! Mit freundlicher Unterstützung von Coca-Cola, INTERSPAR, Marionnaud und NIVEA. Danke! Ja, ich will Pate werden! Rufen Sie uns an – Sylvia Fink und Hans Gregoritsch informieren Sie gerne unter unserer kostenlosen Tel.-Nr. 0800 / 80 80 81 oder unter www.sos-kinderdorf.at 21 REPORTS BERICHTE 8th Pangborn Sensory Science Symposium The 8th Pangborn Sensory Science Symposium, a meeting honoring the work and contribution of Rose Marie Pangborn in the field of sensory science, organized by the Italian Society of Sensory Science in collaboration with Elsevier started on 26th July 2009 and finished on 30th July 2009 in Florence (Italy). This meeting, which is recognized as the most important scientific symposium for the disciplines of sensory and consumer science, was attended by specialists in sensory science from all over the world (Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, UK, USA, etc.) as well as five Austrian delegates participating – Eva Derndorfer, Klaus Dürrschmid, Dorota Majchrzak, Barbara Siegmund and Marlene Woda. The following main topics were offered: • Fundamentals of sensory (physiology, perception/ receptors, multimodal sensory perception, genetics, psychophysics, brain imaging, odour perception, astringency, chemestesis) • Consumer behaviour (attitudes and hedonic responses to food, hedonics and food choice, social/ cultural, age/gender effects, linking attributes to consumer needs, emotion and memory in sensory science of food, dynamics in food preferences, preferences and healthy choices, statistical techniques, market research) • Effective use of sensory evaluation (application in the food industry, sensory quality assurance, best practices, testing under non standard conditions/ meal research, data analysis, management of sensory panels, new technologies/packaging and sensory properties of food, sensory-instrumental relationship, product development, sensory evaluation and gastronomy) • Non Food (methods, applications, psychophysics, quality assurance, sensory interactions, sensoryinstrumental relationship, consumer behaviour) • The Future (new methods and research tools, new research areas, new data analysis technique, training and education in sensory science, integration of sensory science with other disciplines) Sensory food science The first keynote speakers, Erminio Monteleone (University of Florence, Italy) and Hely Tuorila (University of Helsinki, Finland) gave an overview about the different issues of sensory science in their presentation “Sensory food science: opportunities and challenges”. They accentuated sensory food science as the in- 22 tersection of many disciplines, e.g. food science, psychology, biology and health science, which has grown rapidly in the past 15-20 years and requires proper use of sensory analysis in the future in order to contribute significantly to the following topical areas: • Development of healthful, tasty foods for normaland overweight population. • Consumer responses to alternative production techniques considered because of societal or production changes. • Identification and testing of cross-cultural food preferences which are increasingly important due to globalization of the market and to increasing immigration. • The development of catering services and the determinants of meal acceptance and overall consumer satisfaction. • The development of foods from alternative or novel materials. In the other keynote presentation “Sensory science and salt: How can sodium intake be reduced?” Gary Beauchamp from the Monell Chemical Senses Center, USA reported about two broad approaches to reducing salt intake: Change consumer perception and/or change the composition of foods. He discussed the possibility of using the molecular receptor for salt to discover salt substitutes or salt enhancers and the importance of behavioural researchers´ work relating to experiences with high or low salt during fetal development, infancy and early childhood. G. K. Beauchamp concluded that much more research is required to verify these indications and to specify relevant parameters. Coding of odours An interesting lecture treated of the “Peripheral coding of odours: From psychophysics to biochemistry”. In the past psychophysical information provided different numbers of primary odours whereas recent acquisitions of molecular biology have led to the identification of about 350 olfactory receptors in the human nose and thus setting an upper limit to the number of primary odorants. Paolo Pelosi from the University of Pisa, Italy therefore revisited the psychophysical data in the light of the most recent information provided by molecular biology and concluded that the encoding of the olfactory messages in the odorant molecules appeared extremely complex, as each stimulus needed several independent parameters (size, shape, position and nature functional groups, confirmation, etc.) to be correctly described. ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 Chemical input – sensory output Plenary speaker Andrea Büttner (University ErlangenNürnberg and Fraunhofer-Institute for Process Engineering and Packing, Germany) talked about “Chemical input – sensory output: Diverse modes of physiologyflavour interaction”. She reported that flavour compounds effectuate development of systems either to achieve attraction (sweet tastants, fruity odorants) or to induce rejection (bitter tastants, offensive smells). Because of diverse biological sources of these compounds structural diversity was wide ranging and as a result the human body exhibited diverse strategies or patterns for interaction with these flavour chemicals. Some compounds showed high specificity and activity in receptor response while others were broadly inefficient. Certain compounds were metabolized by enzymes, whereas others interact with mucosal tissues. Another mode of chemical-physiological interaction she reported about were compounds that enhanced specific consumption patterns, e.g. modification of chewing. Descriptive analysis Wender Bredie from the University of Copenhagen, Denmark presented “The future of descriptive sensory methodology – faster and more versatile” and concluded that descriptive sensory analysis needed still development, although it is widely used in sensory research, product innovation and quality control. Fast descriptive methods e.g. quick screening in product developments and performing fair product testing which require formalized protocols were postulated. Wider approaches for measurement of sensory product performances including eating-related and postingestion related perceptions as well as exploring contexts and situational effects should be done. Sensory language In the lecture “sensory language from a linguistic perspective – new ways in better understanding taste communication” by Jeannette Nuessli Guth from ETH Zurich, Switzerland experimental data from focus groups showed that in the everyday language of German a large number of expressions are used to define taste perception. Besides taste qualities these words also implied additional dimensions such as other senses, emotional or evaluative aspects, reference to cultural norms/values or use of specified products and situations. Whole product assessment The aim of L. Jamieson´s (Unilever R&D Colworth, UK) report “Sensory journey of a product – methods for whole product assessment” was to discuss adaptations to two temporal sensory evaluation methods in order to evaluate the sensory character throughout consumption of the whole product. Two methods, on the one hand time intensity (TI), in which sensory pan- ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 ellists were asked to consume uniform portions of a product at set intervals until the entire product was consumed and to continuously evaluate the sensory product that was of interest was applied, on the other hand temporal dominance of sensations (TDS) in which panellists were asked to consume uniform portions of a product to select the dominant attribute at set intervals until the entire product was consumed, were used. Finally it was concluded that both methods were useful additions to the repertoire of sensory methods that are currently available. Innovative properties The plenary presentation “Foods and beverages with innovative sensory properties: Relation to prior experience” by Conor Delahunty´s from CSIRO Food Science Australia aimed to define present knowledge regarding familiarity with sensory properties in relation to sustained likes and dislikes and to consider best way to measure this. Furthermore the concept of perception innovation was introduced, which is providing a terminology that considers in what qualities and at what intensity sensory properties need to be changed away from what has been prior experienced in order to achieve new product sensory innovation with less risk of product failure. Umami taste Jos Mojet from Wageningen University, Netherlands presented the study “The use of umami taste in salt reduction” and discussed a practical method to define the percentage of salt, that can be replaced using naturally brewed soy sauce while retaining overall taste intensity and pleasantness for Western European consumers. Five concentration ratio´s of salt and soy sauce were used to establish the pleasantness for the different dishes: plain green salad with a simple dressing, tomato cream soup and stir-fried slices of pork. The results showed that the replacement of salt by soy sauce was possible and that the degree of replacement depended on the type of food. In salad dressings salt can be reduced with 37.5%, in tomato cream soup with 17% and in stir-fried pork with 29%. “Glutamate and conditioned appetitive behaviors in humans” was the topic of John Prescott´s lecture (University of Newcastle, Australia). The author presented a study that was carried out in order to determine if a liking of novel flavours can be conditioned using glutamate by repeatedly experiencing novel soups with or without added MSG (0.5% w/w) and either consuming it (250 ml) or tasting it (10 ml) and reported that subjects consuming a soup with MSG showed a significantly greater increase in liking than those receiving the soup without added MSG or those tasting the soup with added MSG. He concluded that soups with added MSG stimulated increased hunger and consumption and suggested post-ingestive ef- 23 fects of glutamate as well as the influence of food-related motivational states. Genetic variations In the presentation “Biological-based variation in perception of oral sensations and liking of alcoholic beverages: Role of gender, PROP responsiveness and thermal taste” Gary Pickering (Brock University, Canada) reported that an important factor explaining differences in perception of chemosensory stimuli is genetic variation. He referred to the PROP sensitivity, also expressed as PROP taster status (PTS), as well as to the more recently identified thermal taster status (TTS), which may constitute up to 50 % of the population, perceive phantom tastes when small areas of the tongue are heated or called. PROP super tasters and thermal tasters, who evaluated several foods and beverages using a 7-point hedonic scale, rated most taste, trigeminal and flavour stimuli as significantly (p<0.05) more intense than PROP normal and thermal normal tasters. There was no difference observed between genders. The findings showed that PTS and TTS affected responsiveness to multiple oral sensations and provided further evidence of the role of biological factors in explaining individual variation in chemosensory perception and food/beverage behaviour. Taste of fatty acids Jessica Stewart from Deakin University, Australia presented the study “Oral fatty acid sensitivity determines fat consumption and anthropometry”, which aimed to evaluate the ability to taste FA (fatty acids) at low concentrations and to determine if any differences existed between individuals who could or could not detect FA in regards to their food intake, BMI and perception of fat in food. 54 subjects were screened for FA sensitivity using 1.4 mM oleic acid in non-fat milk via triplicate triangle tests and additionally a fat ranking task using custard with 0, 2, 6 and 10% fat was applied. 22% of the subjects, who could detect FA samples from control samples three times out of three tests, were “fatsensitive”. The sensitivity correlated with lower energy intake (p<0.05), BMI (p<0.05), fat consumption (p=0.08) and increased capacity to determine the fat content of custard (p<0.05). Finally J. E. Stewart suggested that the ability to taste FA at low concentration influences the consumption of food, fat and the perception of fat in food. As a consequence it was pointed out that individuals who were “fat-insensitive” might consume excess food and be less aware of the fat content in food, which has implications for weight gain and health. Acceptance of veggies In “Influence of early weaning practices on acceptance of vegetables in 15- and 36-month old children” Andrea Maier from the Nestlé Research Center in Switzerland presented two promising approaches to 24 increase acceptance of vegetables by (1) offering infants a variety of vegetables (purée changed every day for 10 days vs. no change) or (2) offering 7-month-old infants an initially disliked vegetable at eight subsequent meals. Discussing the results A. Maier reported that at 15 months effects of early variety were still evident: Children from the high variety group liked more vegetables than children given no variety (p<0.05). At 36 months infants, who were offered different sorts of vegetables, liked significantly more vegetables. This fact could be a consequence of neophobia or early variety experience. Infants who repeatedly consumed initially disliked vegetables more readily accepted it. Point of view – obese versus normal weighted Klaus Dürrschmid from the Austrian University of Natural Resources and Applied Life Science reported in his presentation “Obese persons have a specific view on food” that there were significant differences in the looking behaviour of obese and normal weighted persons, when they were confronted with visual stimuli of food of obvious different energy content and of composed dishes. Pictures with one food were presented to 30 persons with a BMI higher than 30 and to 30 persons with a BMI between 20 and 25. Their visual behaviour was tested using a Tobii eye tracking plant. The presented findings showed several differences in the course of saccades and in the average time obese and normal weighted individuals were looking at different regions of the presented visual stimuli. Poster presentations Among more than 500 posters several works were presented by Austrian delegates. Klaus Dürrschmid contributed with two posters. The first one treated of “Sensory eye tracking and evaluation of smoothie products” characterizing five different orange coloured smoothies available on the Austrian market applying quantitative descriptive analysis (QDA) and acceptance tests. In QDA three products were quite similar, one had a clear vegetable note and the fifth product differed significantly in the creaminess. Despite differences in the QDA, in the acceptance test it became clear that the vegetable note and the creaminess did not have any impact on the overall acceptance. The importance of the position of the product for visual attention was revealed in the eye tracking investigations. In the other poster “The taste of Vienna – a sensory evaluation training programme for the food industry of Vienna” the author gave information about a novel developed training programme to improve the perceptional skills of the involved sensory test persons and the methodological skills of the persons designing and running the tests. Screening tests were performed with 60 employees in food industry, 40 of them were selected for training. The aim of the test ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 methods in the training, which were divided in the modules new product development, quality assurance and consumer tests, was to show the way to new solutions of existing sensory problems in the company. After five weeks of intense training the perceptional performance of the sensory panel improved, the motivation of the existing panel members became better, more employees committed to the sensory tasks in every day production and the methodological level of the company increased significantly. Dorota Majchrzak (University of Vienna) presented as a poster the results of “Sensory evaluation of omega-3fatty acid-enriched hen´s egg”. In the investigation two different sorts of omega-3 fatty acids enriched hen´s eggs were compared to regular eggs using QDA. The sensory properties of white and yolk eggs samples were evaluated by rating the intensity of appearance, odour, flavour, aftertaste and texture on a 10-unit scale, while the consumers´ preferences were determined by applying the paired difference test. The results of the QDA showed significant differences regarding the texture of egg yolk and egg white. Cooked egg whites of the two sorts of omega-3 fatty acid-enriched eggs turned out to be firmer (p<0.01) and more crumbly (p<0.05) in comparison to the regular egg. One sort of the omega-3 fatty acid enriched hen´s eggs had the softest egg yolk, which was associated with the highest creaminess and the lowest crumbliness and gumminess. The paired difference test showed however no significant differences between enriched and non-enriched eggs. The poster “The flavour of strawberries – can we enhance it on the natural way?” contributed by Barbara Siegmund from the Graz University of Technology aimed to prove the interaction between the strawberry plant and bacteria which are supposed to be responsible for the formation of furanoid compounds that influence the strawberry flavour in order to enhance it. The sensory properties of treated and untreated strawberries were evaluated by a trained sensory panel applying QDA. The “aroma pattern” of the fruits was analysed using headspace GC-MS. The results showed differences between the sensory properties of treated and untreated strawberries. B. Siegmund concluded that further experiments are required to optimize the application mode and to enhance the flavour of strawberries on a natural way. The independent sensory consultant Eva Derndorfer presented as a poster the work “Cognitive associations of colours and flavours – and their dependence on peoples´ wine, fruit and vegetable consumption”. Applying an online questionnaire which contained four differently coloured areas (light blue, cream yellow, light green, red) associations between (wine) colours and sensory attributes were investigated. First ERNÄHRUNG/NUTRITION, VOLUME 34, 1-2010 the respondents´ taste/flavour association with each colour was asked in an open question. Additionally each colour had to be ranked for 19 attributes and in the third part the panellists were asked to name a food or drink they associated with each colour. The most common associations to the open question were: yellow with sweet, creamy, mild; green with sour, fresh, fruity; red with hot, bitter, sweet, fruity, winey and blue with artificial, fresh, sweet, neutral. In the ranking task relations of the colour red with winey, spicy, burnt, earthy and woody were found, while green wasn´t associated with specific terms. Yellow was frequently related to sweet, fat, milk and yeast whereas blue had the lowest rank with metallic and artificial. There was also evidence that the respondents´ consumption patterns influenced their colour-flavour-associations. The results of the diploma thesis “Sensory properties and antioxidant capacity of arabica- and robustacoffee prepared as filter brews” were presented as a poster by Marlene Woda from University of Vienna. The total antioxidant capacity (TAC) of three arabica and three robusta blends prepared as filter brews was measured photometrically. Additionally the sensory properties of Santos (arabica) and Uganda (robusta), which possessed similar antioxidant potential, were evaluated over two sessions applying QDA. The TACanalysis showed that the average antioxidant potential of robusta coffee was significantly (p<0.05) higher than the one of arabica coffee. In the QDA the mean overall sensory quality of arabica coffee was rated significantly (p=0.000) higher than the one of robusta coffee. A fact that was attributed to the burnt, woody and earthy odour and flavour properties which were significantly (p<0.01) higher in robusta than in arabica. In contrast, the intensity of fruity odour and flavour as well as sweet taste was significantly (p<0.05) higher in arabica- than in robusta-coffee. Concluding the 8th Pangborn Sensory Science Symposium in Florence it can be summarized that a comprising and interesting programme was offered providing the delegates lots of new findings and indicating future tasks for sensory and consumer science such as the development of a uniform sensory language, new methods, which are easy to handle, as well as interdisciplinary scientific approaches especially with genetics and biochemistry concerning a better understanding of perception. Address of the authors: Ao. Univ.-Prof. Dr. Dorota Majchrzak Mag. Marlene Woda Department of Nutritional Sciences University of Vienna Althanstraße 14, 1090 Vienna [email protected] 25