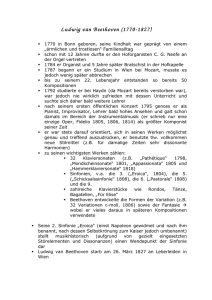

The Complete Symphonies

Werbung