`racial biology` at the german charles university in prague, 1940–1945

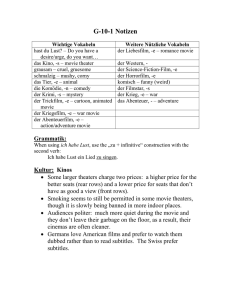

Werbung