Newsletter Q3 2015

Werbung

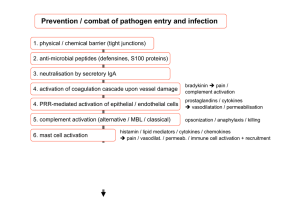

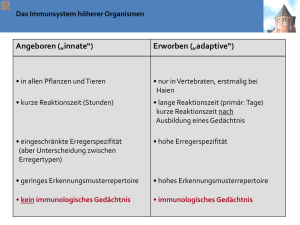

Wissenschaftliche Gesellschaft zur Forschung und Weiterbildung im Bereich nahrungsmittelbedingter Intoleranzen Newsletter Q3/2015 Autor: Mag. Florian Forster, PhD The english version of this text starts at page 6. Das mukosale Immunsystem Die Schleimhäute umspannen eine enorme Fläche, die vom Immunsystem geschützt werden muss. Die Oberfläche des Dünndarms allein entspricht ca. 400m2, was 200-mal größer ist als die Oberfläche der Haut. Mukosale Oberflächen müssen dünne und durchlässige Barrieren sein, um ihre Aufgaben in z.B. Gas-Austausch (Lunge), sensorische Aufgaben (Auge, Nase, Mund und Kehle) und in der Nahrungsaufnahme wahrzunehmen. Das hat zur Folge, dass Schleimhäute sehr anfällig für Infektionen sind. Deshalb ist es auch wenig überraschend, dass Schleimhäute die Hauptroute für das Eindringen von Pathogenen darstellen. Ein weiterer wichtiger Punkt ist, dass die Schleimhäute auch mit einer enormen Anzahl von Substanzen in Kontakt treten, die zwar körperfremd, aber keine pathogene sind, d.h. nicht gefährlich sind. Der Darm ist z.B. 10 – 15 kg Essensproteinen pro Jahr pro Person ausgesetzt. Würden diese Nahrungsproteine eine Reaktion im Immunsystem hervorrufen, wäre das nicht nur verschwenderisch, sondern auch höchst gefährlich. Tatsächlich sind Immunreaktionen gegen ungefährliche Nahrungsmittelbestandteile verantwortlich für eine Reihe von relativ häufigen Erkrankungen, wie Zöliakie (hervorgerufen durch eine Immunreaktion gegen Gluten – ein Weizenprotein) oder chronisch-entzündlichen Darmerkrankungen, wie Morbus Crohn (verursacht durch eine Immunantwort gegen kommensale-Bakterien). Dafür hat das mukosale Immunsystem im Vergleich zum Immunsystem des restlichen Körpers – man könnte dazu sagen, das systemische Immunsystem – eine Reihe von speziellen Eigenschaften (Siehe Tabelle 1). Tabelle 1 Spezielle Eigenschaften des mukosalen Immunsystems Enge Interaktion zwischen Mukosa und lymphoiden Gewebe. Diskrete Kompartments und organisierte Strukturen, wie Peyer’s patches, lymphoide Follikel und Mandeln. Spezialisierte Antigen Mechanismen, wie M-Zellen. Effektormechanismen Aktivierte / Memory T-Zellen prädominieren auch, wenn keine Infektion vorliegt. Natürliche Effektor / Regulatorische T Zellen, welche nicht spezifisch aktiviert werden. Immunregulatorische Aktive Eindämmung der Immunantworten. Maßnahmen Inhibierende Makrophagen und Toleranz induzierende dendritische Zellen. Anatomische Eigenschaften Intestinale Lymphozyten können entweder einzeln verteilt im Darm vorkommen, wo sie Effektorfunktionen ausführen oder in organisierten Geweben, wo sie die Immunantwort induzieren. Die organisierten Strukturen heißen Darm assoziierte lymphoide Strukturen (gut associated lymphocyte tissues (GALT)). Inkludiert im GALT sind Peyer’s patches und isolierte lymphoide Follikel im Dünndarm. Es gehören aber auch die immunologischen Strukturen wie der Wurmfortsatz, die Mandeln und die Polypen zum GALT (Siehe Figur 1). Das Immunsystem des Darms hat spezielle Routen für die Aufnahme von Antigen. Antigene müssen zuerst die epitheliale Barriere durchbrechen, um das mukosale Immunsystem zu aktivieren. Dafür gibt es spezielle Routen und Mechanismen der Antigen Aufnahme. Eine dieser Routen geht durch spezielle Epithelzellen, die M-Zellen (microfold cells) heißen. M-Zellen besitzen keine Mikrovilli, keine Schleimschicht und sezernieren keine Verdauungsenzyme. Deshalb Figur 1: Links: Schematisches Diagramm des Mukosalen Immunsystems. Gezeigt wird ein Peyer’s patch mit einer M-Zelle (MC) in einer epithelialen Zellschicht (IEC) und assoziierte Immunzellen, wie dendritiasche Zellen (DC), Makrophagen (Mφ) und intraepitheliale Lymphozyten (IEL). Rechts Peyer’s patch mit M-Zellen. Die M-Zellen sind klar unterscheidbar von den Epithelzellen, weil sie eine glatte Oberfläche ohne Mikrovilli haben. Das Bild links wurde adaptiert von 1, das Bild rechts wurde adaptiert von 2. sind sie im direkten Kontakt mit dem Nahrungsbrei und prädestiniert für die Aufnahme von Antigenen. M-Zellen nehmen kontinuierlich Moleküle und Partikel vom Darm durch Endo- und Phagozytose auf und transportieren diese durch den Prozess der Transzytose durch die Zellen durch zu den unter den M-Zellen liegenden Peyer’s patches. Peyer’s patches sind organisierte lymphatische Gewebe, die direkt unter der epithelialen Oberfläche des Dünndarms liegen. Diese bestehen aus höchst aktiven B Zellfollikel mit eingestreuten T Zell reichen Regionen (T cell dependent areas, TDA). In der Schicht zwischen Epithelium und in diesem Fall den M Zellen und den Peyer’s patches liegt der subepitheliale Dom, der reich an T- und B-Zellen ist. Die Basis der M-Zellen ist extensiv gefaltet. In den dadurch entstehenden Falten sitzen die dendritischen Zellen und nehmen direkt die Antigene von den M Zellen auf. Dadurch wandern die dendritischen Zellen in die Peyer’s patches und aktivieren dort die T Zellen (Siehe Figur 1 links). Eine andere Möglichkeit für das mukosale Immunsystem um Antigene zu identifizieren, sind dendritische Zellen, die mit ihren Fortsätzen durch die epitheliale Barriere ohne diese zu zerstören in das Darmlumen reichen und direkt dort Antigene aufnehmen (Siehe Figur 2). Figur 2: Schematische Darstellung (links) und Mikroskopiebild einer dendritischen Zelle, die mit ihren Fortsätzen durch die epitheliale Zellschicht in das Darmlumen reicht. Bild adaptiert von 3. Effektormechanismen des mukosalen Immunsystems Nun da wir die speziellen Komponenten und Wege der Aktivierung des mukosalen Immunsystems kennen, können wir die speziellen Möglichkeiten des mukosalen Immunsystems besprechen, wie auf eine Infektion zu reagieren ist. Ein Effektormechanismus, der schon lange bekannt ist, sind Antikörper der Subklasse Immunglobulin A (IgA). Vor über 50 Jahren fand man heraus, dass diese Klasse die dominierende Klasse der in den Darm sezernierten Antikörper ist und dass IgA aber nicht IgG sezerniert wird. Desweiteren ist IgA mit einer Tagesproduktion von 5 Gramm, das mit Abstand am meisten produzierte Immunglobulin. IgA wird massiv von B Zellen in den Peyer’s Patches produziert, aber auch an anderen Stellen unterhalb der epithelialen Zellschicht. IgA-Dimere werden dann von unreifen Epithelzellen mithilfe spezieller Rezeptoren aufgenommen und in das Darmlumen abgegeben. Im Darm bindet das IgA an die Schleimschicht, die die Epithelzellen umgibt und bleibt damit in räumlicher Nähe zu den Epithelzellen. Sezerniertes IgA bindet Pathogene und Toxine, die von Darm Pathogenen gebildet werden. Es kann aber auch Pathogene in den Epithelzellen neutralisieren, bzw. Toxine aus der subepithelialen Schicht in den Darm exportieren. D.h. die Hauptaufgabe der IgAs ist die Erreichbarkeit der Körperzellen durch Pathogene einzuschränken und dadurch das Risiko einer Entzündung und der damit einhergehenden Gewebsschädigung zu minimieren. Neueste Forschungsergebnisse zeigen, dass IgAs auch sehr wichtig sind für das symbiontische Zusammenleben zwischen einem Individuum und seiner Darmflora. Elegante Experimente in Mäusen zeigten, dass es falls die Expression von IgAs verringert ist oder ganz fehlt, bzw. falls die produzierten IgAs von schlechter Qualität sind, es zu einem Überwachsen des Dünndarms kommt bzw. dass die Zusammensetzung der Mikrobiota verändert wird 4,5. Das basiert nicht nur auf dem coating der Bakterien mit IgA, sondern es wurde auch gezeigt, dass die Bindung von IgA an das Bakterium dessen Stoffwechsel verändert 6. Wegen dem engen Kontakt mit nicht-selbst Partikeln, sind T-Lymphozyten mit ungewöhnlichen Phänotypen weit verbreitet und verantwortlich für eine Reihe ungewöhnlicher Effektor Funktionen. Z.B. zeigen die meisten T Zellen des mukosalen Immunsystems eine hohe Expression des Rezeptors CD45RO. Ein Rezeptor der sonst nur auf aktivierten oder Memory T Zellen, welche selten sind in der systemischen Immunantwort, zu finden ist. In Krankheiten wie der Zöliakie oder in chronisch entzündlichen Darmerkrankungen sind diese Zellen klar verantwortlich für die Schädigung der Darmschleimhaut. Wie auch immer ist deren normale Funktion im Immunsystem noch nicht geklärt. Wahrscheinlich sind sie verantwortlich für das Verhindern von Hypersensitivitätsreaktionen gegen Nahrungsmittel Proteine und die Darmmikrobiota. Eine andere Klasse der Immunkräfte des mukosalen Immunsystems sind die sogenannten Intraepithelialen Lymphocyten (IEL), welche direkt im Epithel, zwischen den Epithelzellen sitzen. 90 Prozent der IEL sind T Zellen. Viele dieser T Zellen besitzen einen ungewöhnlichen T Zellrezeptor mit einer gamma und delta Kette anstatt einer „normalen“ alpha / beta Kette. Eine andere Population besitzt einen ungewöhnlichen CD8 Korezeptor, der aus 2 alpha Ketten anstatt einer alpha und einer beta Kette besteht. Die meisten dieser Zellen zeigen auch wieder einen aktivierten Phänotyp, brauchen keine Hilfe von Antigen präsentierenden Zellen für ihre Aktivierung und zeigen eine verringerte Variabilität des T Zellrezeptors, was wiederum bedeutet, dass sie nur eine geringe Anzahl an Antigenen erkennen. Eine Erhöhung der Anzahl an IELs spricht für eine anhaltende chronische Entzündung wie z.B. in der Zöliakie. Im Krankheitsbild der Zöliakie exprimiert ein bestimmter IEL Zelltyp hohe Pegel an aktivierenden C-type Lektin NK Rezeptor NKG2D. Dieser Rezeptor bindet an MHC artige Rezeptoren MIC-A und MIC-B. MIC-A und MIC-B werden nur exprimiert auf gestressten Epithelzellen. Stress kann das Ergebnis einer viralen Infektion sein. Dadurch schützen die NKG2D exprimierenden IELs vor viralen Infektionen. Stress und dadurch die Expression von MIC-A und MIC-B kann aber auch das Resultat sein der Antwort der Epithelzellen auf Gliadin Peptide. In diesem Fall führen die normalerweise gutartigen IELs zu einer nicht gewollten Zerstörung der Epithelzellen in Antwort auf eine Reizung verursacht durch normale Essensbestandteile, wie Gluten (Siehe Figur 3). Figur 3: Im Cartoon ist die Aktivierung von intraepithelialen Lymphocyten durch von Gliadin gestressten Epithelzellen gezeigt. Adaptiert nach 3. Auch wenn die Wissenschaft in den letzten Jahren bereits vielfältige und weitreichende Einsichten in das mukosale Immunsystem gebracht hat, wartet noch viel darauf entdeckt zu werden in dem faszinierenden System. 1. 2. Azizi, Ali; Kumar, Ashok; Diaz-Mitoma, Francisco; Mestecky, Jiri (2013): PLOS Pathogens. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001147.g001. Cover picture Journal of Immunology, June 1, 2003; 170 (11) 3. Charles A. Janeway: Immunologie. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag; 5. Auflage (2002) ISBN 3-8274-1079-7 4. Fagarasan S., Muramatsu M., Suzuki K., Nagaoka H., Hiai H., Honjo T.; 2002. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science 298:1424. Suzuki K., Meek B., Doi Y., et al.; 2004. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101:1981. Peterson D. A., McNulty N. P., Guruge J. L., Gordon J. I.; 2007. IgA response to symbiotic bacteria as a mediator of gut homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe 2:328. 5. 6. The mucosal Immunsystem Author Mag. Florian Forster, PhD The mucosal surfaces comprise an enormous area, which has to be protected. The human small intestine has a surface area of almost 400m2. This is 200 times more than the skin. Mucosa surfaces have to be thin and permeable barriers to fulfil their duties in for instance gas exchange (the lung), sensory activities (eyes, nose, mouth and throat) and food absorption (small intestine). This makes them extremely vulnerable for infections and it’s no surprise that the vast majority of pathogens are invading by this route. A second important point when talking about mucosal surfaces and the immune system is that they are in addition portals for the entry of non-dangerous non-self and therefore non-pathogenic antigens. The gut for instance is exposed to an estimated 10 – 15 kg of food proteins per person per year. It would be wasteful and more over very dangerous if the immune system would react to those proteins. In fact immune responses of this kind are thought to be the cause for relatively common diseases like coeliac disease (caused by an immune response against gluten - a wheat protein) or inflammatory bowel diseases like Crohn’s disease (caused by a response to commensal bacteria). The mucosal immune system has compared to the immune system of the remaining body – let’s call it the systemic immune system – distinct features as seen in table 1. Anatomical features Effector mechanisms Immunoregulatory environment Distinctive features of the mucosal immune system Intimate interaction between mucosal and lymphoid tissue Discrete compartments and organized structures like Peyer’s patches, lymphoid follicles and tonsils Specialized antigen uptake mechanisms like M-cells Activated / memory T cells predominate even in the absence of infection Natural effector / regulatory T cells, which are nonspecifically activated, are present. Active down regulation of immune responses predominate Inhibitory macrophages and tolerance-inducing dendritic cells Table 1 Lymphocytes of the intestine are found scattered throughout the intestine where they carry out effector functions or in organized tissues, where the immune response is initiated. The organized structures are called gut associated lymphocyte tissues (GALT). Included in the GALT are Peyer’s patches and isolated lymphoid follicles in the small intestine. But also the appendix, the tonsils and adenoids in the throat are members of the GALT (see figure 1). The immune system of the intestine has distinctive routes for antigen uptake. Because antigens have first to pass through the epithelial barrier before they can activate the mucosal immune system there have to be distinct routes and mechanisms of antigen uptake. Figure 1: Left: Schematic diagram of the mucosal immune system. Shown is a peyer’s patch with an M cell (MC) in a cell layer of intestinal epithelial cells (IEC) and associated immune cells like dendritic cells (DC) macrophages (Mφ) and intra epithelial lymphocytes (IEL). Right: Peyer’s patch with M-cells. The M-cells are clearly distinguishable from the intestinal epithelial cells because they have a surface without micro villi. The picture in the left was adopted from 1, the picture in the right is adopted from 2 One such route is through special epithelial cells called microfold cells (M-cells). M cells don’t have microvilli or a mucus layer and they don’t secret digestive enzymes (see figure 1). Therefore they have direct contact with the chyme and are predestined for antigen uptake. They continually take up molecules and particles from the gut lumen by endo- and phagocytosis and transport them by a process called transcytosis through the cell to the peyer’s patches lying underneath the M-cells. Peyer’s patches are highly organized lymphatic tissues directly located beneath the epithelial surface of the intestine. Each comprises highly active B cell follicles with interspersed T cell dependent areas (TDA). In the layer between the epithelium in this case the M-cells and the Peyer’s patch lies the subepithelial dome, rich in T- and B-cells but especially in antigen up taking dendritic cells. The basis of the M cells is extensively folded forming pockets in which the dendritic cells are located. Particles transcytosed by the M-cells are passed on to the dendritic cells, which in turn can activate T cells in the Peyer’s patch (see figure 1 left). Another possibility to identify antigens for the mucosal immune system are dendritic cells which reach with their extensions into the gut lumen without disturbing the integrity of the epithelial cell layer (see figure 2). Figure 2: Schematic drawing (left) and microscopic picture of a dentritic cell reaching with its appendices into the gut lumen. Picture adopted from 3. Effector mechanisms of the mucosal immune system Now that we know the special ways how the mucosal immune system gets activated we can discuss some special ways how the mucosal immune system reacts to antigens. One of the first special effector mechanisms of the mucosal immune system identified are antibodies of the subclass IgA. More than 50 years ago it was found that this class predominates in mucosal secretion and that IgA but not IgG is secreted into the gut. Moreover IgA is by far exceeding with a production of 5 grams per day the production of all other antibody sub classes. IgA is massively produced by B cells from the Peyer’s patches but also in other sites beneath the epithelial barrier. Dimeric IgA molecules are than up taken from immature epithelial cells located at the base of intestinal crypts by a special receptor and consequently secreted into the gut lumen. IgA in the gut is not floating freely around but is bound to the mucus layer coating the epithelial surfaces. Secreted IgA is able to bind and neutralize pathogens and toxins produced by pathogens. Moreover IgA is also able to bind and neutralize antigens inside of epithelial cells and in addition to export toxins, which already have passed the epithelial barrier back to the gut. So the main function in defence is to limit the access of pathogens to body cells and therefore minimize the risk of inflammatory damage of these fragile tissues. Recent research shows that IgA plays also a very important role in the symbiotic interplay between an individual and their commensal gut microbiota. Elegant experiments in mice showed that if the expression of IgA is lacking or has not the desired quality first the microbiota over grows the intestine and second also the composition of the gut microbiota is changed 4,5. This is not only achieved by simple coating of the bacteria but it was also shown, that binding of IgA to bacteria is able to alter the metabolism of the bacteria 6. Because of the close contact with non-self particles, unusual T lymphocytes are widely spread in the mucosal immune system and are responsible for a number of unusual effector functions. For instance most of the T cells of the mucosal immune system show high expression of the receptor CD45RO. A receptor only expressed on activated or memory T cells, which are very low in number in the systemic immune system. In disease conditions like celiac disease or inflammatory bowel disease these cells are clearly responsible for the tissue damaging effect of the immune system. However their function in a normal working immune system remains elusive. Most likely they are important for preventing hyper sensitivity reactions to food proteins and commensal bacteria. Another class of special immune forces in the mucosal immune system are the so called intraepithelial lymphocytes (IEL), which are directly located in the epithelium. 90% of IEL are T cells. A number of this T cells carry an unusual T cell receptor with a gamma and delta chain instead of the “normal” alpha / beta T cell receptor. Another population carries an unusual CD8 receptor existing of 2 alpha CD8 chains instead of an alpha and beta chain. Most of these cells again show an activated phenotype, they don’t need the help of antigen presenting cells to start with their effector functions and show restricted variability in their T cell receptors, which means they are able to detect just a restricted repertoire of antigens. An increase in the number of IELs speaks for an ongoing chronic inflammation like in for instance celiac disease. In celiac disease a special kind of IELs expresses high levels of the activating C-type lectin NK receptor NKG2D. This receptor binds MHC like molecules MIC-A and MIC-B. MIC-A and MIC-B are only expressed on stressed epithelial cells. Stress can be the result of a viral infection and therefore the IELs expressing the NKG2D receptor protect from viral infections. However stress and therefore expression of MIC-A and MIC-B can also be induced as a response of epithelial cells to gliadin peptides. In this case the normal beneficial IELs lead to an unwanted destruction of epithelial cells in response to normal food components (see figure 3). Figure 3: Cartoon showing the unwanted activation of immune cells by normal food components like gliadin. Adopted from 3. Although research in recent years has gained valuable insights into the processes of the mucosal immune system a lot more still waits to be discovered of this fascinating system in the system. 1. 2. Azizi, Ali; Kumar, Ashok; Diaz-Mitoma, Francisco; Mestecky, Jiri (2013): PLOS Pathogens. 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001147.g001. Cover picture Journal of Immunology, June 1, 2003; 170 (11) 3. Charles A. Janeway: Immunologie. Spektrum Akademischer Verlag; 5. Auflage (2002) ISBN 3-8274-1079-7 4. Fagarasan S., Muramatsu M., Suzuki K., Nagaoka H., Hiai H., Honjo T.; 2002. Critical roles of activation-induced cytidine deaminase in the homeostasis of gut flora. Science 298:1424. Suzuki K., Meek B., Doi Y., et al.; 2004. Aberrant expansion of segmented filamentous bacteria in IgA-deficient gut. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 101:1981. Peterson D. A., McNulty N. P., Guruge J. L., Gordon J. I.; 2007. IgA response to symbiotic bacteria as a mediator of gut homeostasis. Cell Host Microbe 2:328. 5. 6.