Reform des Fortpflanzungsmedizinrechts

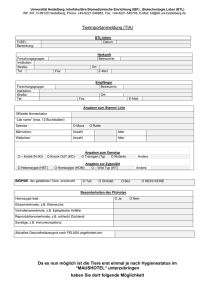

Werbung