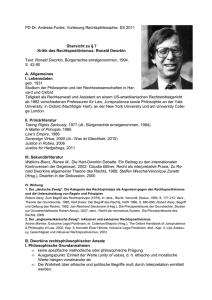

Ethik und Recht - Program in Criminal Justice

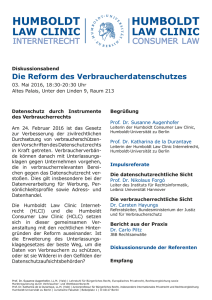

Werbung