German 2R Review Packet

Werbung

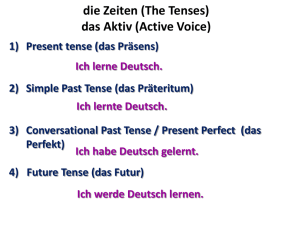

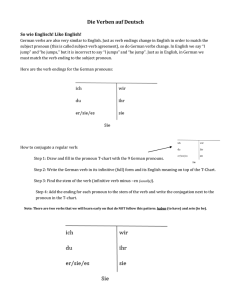

German 2R Final Review Packet Present Tense Review: The present indicative tense in German (indicative merely means a statement of fact, rather than a hypothetical or conditional statement) is much more encompassing than the present indicative tense in English. Use this to your advantage! For example, a German verb conjugated in its present tense could be translated in three ways in English, for example: Ich lese can be translated as: * I read. * I do read. * I am reading. German lacks our present progressive tense (I AM reading, he IS running, etc.), so in a way, English is more difficult for a non-native speaker to learn. Regular verbs, which you have already learned in German I, take the following endings, after they have removed the infinitive –en ending: Singular -e -st -t st 1 person 2nd person 3rd person Plural -en -t -en Frau Muldoon taught you these endings to the tune of Barney’s “I love you, you love me” song. For example, for gehen (to go), which is regular in the present tense, would be conjugated like this: ich gehe du gehst er/sie/es geht wir gehen ihr geht sie / Sie gehen Most verbs follow this model, but some verbs are irregular. For most irregular verbs, the irregularity in the present tense only occurs in the du and the er/sie/es forms, where a vowel change is likely to occur. Examples follow: a ä in fahren, laufen, backen, schlafen, tragen, fallen, etc. Singular Plural fahren – to drive st 1 person fahre fahren 2nd person färhst fahrt rd 3 person fährt fahren e i sprechen, werden, essen, helfen, nehmen, geben, etc. Singular 1st person spreche nd 2 person sprichst 3rd person spricht Plural sprechen sprecht sprechen e ie in lesen and sehen, etc. Other verbs are completely irregular and must be learned individually. The verb sein is a perfect example of this in German, as in English. Please remember when translating an English sentence into German that our present progressive tense is simply translated with the German present tense. Although you might see an English sentence written We are going to the movies, you must avoid the temptation to translate the word are individually from the verb to go! Remember, as I have stressed repeatedly in class, the German phrase wir gehen can be translated into English in any one of three ways depending on context: 1) wir gehen – we go 2) wir gehen – we do go 3) wir gehen – we are going So, the English sentence We are going to the movies would correctly be translated into German by Wir gehen ins Kino. What it takes us English speakers to say in three words, We are going, only takes German speakers two, Wir gehen. Review of the Imperative Mood (Command form): If you are a fan of the Harry Potter books, you may remember the name of one the three unforgivable curses to be the Imperiatus curse. When this curse was used in class on a spider, the witch or wizard would point their wands at it and say, “Imperio!” which is simply Latin for “I command!” Thus, the imperative mood, is what we use when we want to give commands. Give me the pen! Take the money! Go to the door! These are all examples of the imperative mood in English. Although usually we are giving commands to others, we can also give commands to ourselves. In English, for example, the following phrases are examples of this: Let’s go! Let’s take the money! Let us give generously! The imperative mood is actually very easy to form in German. To give commands to one person with whom you would use du, simply remove the –en from the infinitive and add –e. This –e ending is usually dropped in spoken German and quite often in written German as well. The –e is always kept, however, with verbs whose stem end in –d, – t, – ig, and –m or –n after another consonant. To give commands to more than one person with whom you are on familiar terms with, you simply use the present tense ihr form of the verb. To give commands to either one or more than one person with whom you would use the Sie form of address, one simply uses the infinitive form of the verb followed by Sie. If we want to give commands to ourselves, we simply use the infinitive followed by wir. Examples follow below: Irregular verbs: Most irregular verbs with –e in the stem, change this to –i or –ie in the du form, just as they do in the regular present tense. Such verbs never add the ending –e in the du imperative form. The ihr and Sie forms remain unaffected. Sein, as could be expected, is completely irregular again in the imperative. Its forms are sei!, seid!, and Seien Sie! du form ihr form Sie form Wir form Gehe zur Tür! Go to the door! Geht zur Tür! Go to the door! Gehen Sie zur Tür! Go to the door! Gehen wir zur Tür! Let’s go to the door! Sprich! Speak! Sprecht! Speak! Sprechen Sie! Speak! Sprechen wir! Let’s speak! Schlafe gut! Sleep well! Schlaft gut! Sleep well! Schlafen Sie gut! Sleep well! Schlafen wir gut! Let’s sleep well! The German Conversational Past Tense (Present Perfect) The Conversational Past - When Germans talk about what they have done in the past, they use the present perfect tense, also known as the “conversational past” because it is used more in spoken form than in writing. (The other past tense, the “simple past” or Imperfekt is used more in writing, but neither form is used exclusively in written or spoken German.) The present perfect tense is a compound tense that gets its name from the fact that it combines two verb forms (making a compound) to express an action or condition in the past. The present is the present tense of the helping verb (haben or sein) that is combined with the past participle of the verb being used to form the Perfekt, and thus the present perfect tense. For example, to say “I worked on the computer” in German, you would say: “Ich habe am Computer gearbeitet.” The helping verb haben is in the present tense (conjugated to agree with ich) and combined with the past participle of arbeiten to form the present perfect. The past participle always comes at the end of the sentence, unless used in a dependent clause, which we have not yet covered. Unlike the present perfect in English, in which all verbs use a form of “to have” as the helping verb (examples: I have been, she has had, we have gone, etc.), German can use a form of either haben or sein to form this tense. Since most German verbs use haben to form the past tense, it is important to know which verbs use sein. As a general rule, only verbs of motion involving destination, or movement from one place to another, use a form of sein as a helping verb. Exceptions to this rule are the verbs sein itself, bleiben, werden, einschlafen, and a few others. For regular verbs, or weak verbs (schwache Verben), the present perfect tense is formed by conjugating either haben or sein to agree with the subject and adding the past participle, which for regular verbs is formed by adding ge- to the er/sie/es form of the verb. Before providing examples, we must first be able to correctly conjugate the verbs haben and sein in the present indicative tense. sein = to be singular plural 1st person 2nd person 3rd person bin bist ist sind seid sind haben = to singular have 1st person habe nd 2 person hast 3rd person hat plural haben habt haben Below is a list of some regular (weak) verbs you have already learned. arbeiten – to work brauchen – to need dauern – to last, take (time) decken – to set (a talbe) feiern – to celebrate glauben – to believe (+ dat.) hören – to hear jubeln – to cheer kaufen – to buy kosten – to cost lachen – to laugh lernen – to learn machen – to do, make mähen – to mow packen – to pack passen – to fit (+dat.) reden – to talk, speak regnen – to rain reisen – to travel* sagen – to say sammeln – to collect schaffen – to manage, make [it] schenken – to give a present schicken – to send schmecken – to taste schneien – to snow spielen – to play spülen – to wash, rinse tanzen – to dance wandern – to hike* wohnen – to reside, to live wünschen – to wish * Note that the present perfect tense of reisen (gereist) and wandern (gewandert) take the forms of sein (ich bin gereist/gewandert, du bist gereist/gewandert…) as they imply motion from one place to another. To sum up: The present perfect tense is used more frequently in German conversation than in English. It is often called the “conversational past.” * haben + (ge + er/sie/es verb form) * Er hat es gesagt. He has said it. In English, three forms (He has said, He was saying, or He said) may be used. To simplify, only the present perfect form is used throughout. The form gesagt (asked) is called the past participle, which in German is placed at the end of the sentence. * Ich habe ein Fahrrad gekauft. I bought a bike. The past participle of verbs with inseparable prefixes (like be-) is simply the er, sie, es form of the present tense. This is also true of verbs ending in –ieren. * Ich habe meine Freundin besucht. I visited my girlfriend. * Was hast du denn fotografiert? What did you take pictures of? The irregular, or strong verbs (starke Verben), as the term suggests, do not follow the same pattern when forming the past participles as the regular verbs. Therefore, you must learn each past participle individually. * Hast du mit Tanja gesprochen? Have you spoken with Tanja? * Sie ist nach Hause gefahren. She drove home. Verbs that use a from of sein must both (a) indicate motion or change of condition and (b) be intransitive, i.e., verbs that cannot have a direct object. This is true in cases like gehen, laufen, kommen, fahren, schwimmen. * Hast du schon mit Andrea gesprochen? Have you already spoken with Andrea? * Wir sind acht Stunden nach Europa geflogen. We have flown eight hours to \ Europe. Here are the irregular forms for most of the verbs you have learned so far: Infinitive anrufen backen (ä) (to bake) beginnen (to begin) bekommen (to receive, get) bleiben (to stay, remain) bringen (to bring) einladen (ä) (to invite) essen (i) (to eat) fahren (ä) (to drive, go by vehicle) finden (to find) fliegen (to fly) geben (i) (+dat.) (to give) gefallen (ä) (+dat.) (to like) gehen (to go) geschehen (ie) (to happen, occur) haben (to have) helfen (i) (+dat.) (to help) kennen (to know (a person/place)) kommen (to come) Past Participle angerufen gebacken begonnen bekommen (ist) geblieben gebracht eingeladen gegessen (ist) gefahren gefunden (ist) geflogen gegeben gefallen (ist) gegangen (ist) geschehen gehabt geholfen gekannt (ist) gekommen laufen (ä) (to run) lesen (ie) (to read) liegen (to lie, be located) nehmen (i) (to take) scheinen (to shine) schießen (to shoot) schreiben (to write) schreien (to scream) schwimmen (to swim) sehen (ie) (to see) sein (to be) singen (to sing) sprechen (i) (to speak) stehen (to stand) treffen (to meet) trinken (to drink) verlieren (to lose) werden (i) (to become) wissen (weiß) (to know (a fact)) (ist) gelaufen gelesen gelegen genommen geschienen geschossen geschrieben geschrien (ist) geschwommen gesehen (ist) gewesen gesungen gesprochen gestanden getroffen getrunken verloren (ist) geworden gewusst Verbs with separable prefixes have the ge- as part of the participle between the separable prefix and the verb stem. * Susi hat mich angerufen. Susi called me. * Wen habt ihr zur Party eingeladen? Whom have you invited to the party? The accent or emphasis is always on the separable prefix (angerufen, eingeladen), whereas the prefix is never stressed in inseparable prefix verbs. (besucht, vergessen). -ge Busters: The following kinds of verbs will not take a –ge to form their past participles: Verbs with inseperable prefixes, i.e.: be-, ent-, mis-, unter-, ver-, etc. (Er hat den Brief bekommen.) Verbs ending in –ieren, ie.: fotografieren, reparieren, amüsieren, telefonieren, etc. (Ich habe die Lampe repariert.) Verbs That are Commonly Used in the Simple Past Conversationally: As the simple, or narrative past, is mostly reserved for formal written situations, you will not encounter it until German III. The German simple past is, however, used frequently in spoken conversational German for the verbs sein, haben, and for all of the modal verbs. As the simple past forms of most verbs are considered rather stuffy, stiff, and formal, one will encounter the simple past forms of even these verbs with less and less frequency the further south one goes into German speaking regions of Europe, especially Bavaria and Austria. Below are the simple past forms of haben and sein. haben – to have 1st person 2nd person 3rd person Singular ich hatte – I had du hattest – you had er/sie/es hatte – he/she/it had Plural wir hatten – we had ihr hattet – y’all had sie hatten – they had Sie hatten – you had sein – to be 1st person 2nd person 3rd person Singular ich war – I was du warst – you were er/sie/es war – he/she/it was Plural wir waren – we were ihr wart – y’all were sie waren – they were Sie waren – you were The Future Tense / das Futur: In German the future tense (das Futur) occurs less frequently than in English. Even more frequently than in English, German often substitutes the present tense for the future (“Wir sehen uns morgen.” – “We’ll see you each other tomorrow.”) However, German verbs do follow an easy-to-learn and predictable pattern in the future tense. Once you learn the pattern for just about any German verb, you know how all German verbs are conjugated in the future. Even irregular verbs are no exception. Das Futur I: The Basics German uses the basic werden + infinitive formula to form das Futur. To conjugate any verb in the future, you simply conjugate werden and add the infinitive of the verb you want to have in the future. Basically, if you can conjugate werden, you can form the future tense of all verbs. The chart below shows a sample German verb in the future tense. Spielen / To Play Future Tense / das Futur I Deutsch ich werde spielen du wirst spielen er wird spielen sie wird spielen es wird spielen English I will play you (fam.) will play he will play she will play it will play wir werden spielen ihr werdet spielen sie werden spielen Sie werden spielen we will play y’all will play they will play you will play Sample Sentence Ich werde Basketball spielen. Wirst du Schach spielen? Er wird mit mir spielen. Sie wird Karten spielen. Es wird keine Rolle spielen. (It won’t matter.) Wir werden Basketball spielen. Werdet ihr Monopoly spielen? Sie werden Golf spielen. Werden Sie heute spielen? Modal Verbs: Modal verbs are some of the most commonly used verbs in German and are used to modify the meaning of another verb, whether expressed or implied. To want is an English modal verb, it also modifies the meaning of another verb: I want to go, I want to visit, I want to celebrate, etc. When used without another verb, that verb is implied: I want cake = I want to have cake. The German modal verbs are conjugated as “sandwich verbs”, that is the ich and the er/sie/es forms are the same. You really only need to learn to forms for each modal verb in the present tense, the singular and the plural forms. The singular form only ads –st to the du form, while the plural form is the same as the infinitive except for dropping the –en and adding –t for the ihr form. The modal verbs in German in the present tense are as follows: dürfen – to be permitted, may ich darf du darfst er/sie/es darf wir dürfen ihr dürft sie/Sie dürfen können – to be able, can , to know (how) ich kann du kannst er/sie/es kann wir können ihr könnt sie / Sie können müssen – to have to, must ich muss du musst er/sie/es muss wir müssen ihr müsst sie / Sie müssen mögen – to like ich mag du magst er/sie/es mag wir mögen ihr mögt sie / Sie mögen sollen – to be supposed to, should/ought to ich soll du sollst er/sie/es soll wir sollen ihr sollt sie / Sie sollen wollen – to want to, (said to be) ich will du willst er/sie/es will wir wollen ihr wollt sie / Sie wollen To form the simple past tense of any modal verb, which is used more often than the present perfect tense both conversationally and in writing, simply take the stem, drop any umlauts if present, and add the following endings: -te -ten -test -tet -te -ten Examples: ich musste I had to wir mussten we had to du musstest you had to ihr musstet y’all had to er musste he had to S/sie mussten you / they had to The only exception is for the modal verb mögen, for which the past stem is moch* Ich mochte gehen. I wanted to go. * Er mochte mitkommen. He wanted to come along. There is one tricky thing that must be learned concerning the modal verbs müssen and dürfen. Although müssen resembles our English word “must”, if you want to say “must not” you have to use the verb dürfen. Examples: * Du musst gehen! (You have to go! / You must go!) * Du darfst gehen! (You may go. / You are permitted to go.) * Du musst nicht gehen. (You don’t have to go. (but you can if you want to)) * Du darfst nicht gehen. (You may not go. / You must not go. (not permitted)) Also remember that the conjugated modal verb comes in the second position while the infinitive verb it modifies goes at the end of the sentence, except in the formation of questions where the conjugated verb comes first or immediately after a question word. * Darf ich bitte meinen Bleistift spitzen? May I please sharpen my pencil? * Ich kann nichts sehen! I can’t see anything! * Das sollst du nicht sagen! You shouldn’t say that! The Accusative Case: The accusative case is the case of the direct object or the object of certain prepositions. Every sentence must have a subject. The subject is always in the nominative case. The subject is defined as who or what is doing the action. The direct object (accusative) is who or what is being acted upon (receiving the action of the verb). Remember that der as object will change to den while die, and das remain the same. You will also need to know the how the indefinite articles (ein, eine, ein) and ein words (such as the possessive adjectives mein, dien, sein, ihr, sein, unser, euer, ihr, Ihr) are used in both the nominative and accusative cases. Please see the charts relating to this subject on the website. When learning the accusative case, we also learned the accusative pronouns mich, dich, ihn, sie, es, uns, euch, sie, Sie and the prepositions that always take the accusative case (sung to the tune of the Animaniacs theme song or “Head and Shoulders, Knees, and Toes”) durch, für, gegen, ohne, um, bis, wider, entlang. There are charts provided on the website that provide more detailed information. The Dative Case: The dative case is the case of the indirect object. Its question word is Wem? And it tells you to whom or for whom the action of the sentence is intended. There are also certain verbs and prepositions that take the dative case. You learned these prepositions through the Blue Danube Walz: Aus, außer, bei, mit, nach, seit, von, zu, gegenüber In the English sentence: “I sent Grandma a letter.” “I” is in the nominative case, as it is the subject of the sentece, the “who” or “what” that is doing the action; “a letter” is in the accusative case, as it is the direct object (what is being sent); Grandma, would be in the dative case, the to whom or for whom the action is intended: the letter was sent to her. Word Order: Verb in the second position: As I’ve said in class, English has many rules of thumb, but thumbs are flexible and can be easily bent. German’s rule about the conjugated verb coming in the second position is hard and fast, like a fist, thus I’ve called this the rule of fist. As we normally begin sentences with the subject, following it with the verb doesn’t seem to have posed much of a problem. It’s when we begin sentences with other pieces of information, such as time, that we must remember this rule. Remember the acronym T.A.P. (Time, Action, Person) and you should be fine. Also remember that the term second position doesn’t necessarily mean the second word! If many words can answer one question, such as when?, all of those words can be considered to be in the first position which must be followed by the verb, then its subject. Examples: 1) Ich gehe zur Schule am Montag. (I go to school on Monday.) Ich is in the first position. It answers one question, “who goes to school”? The verb gehe is in the second position. 2) Am Montag gehe ich zur Schule. Now the time when I go to school is emphasized. Am Montag, although two words, answers the one question, “When do you go to school?” “On Monday.” The verb then must come in the second position followed by the person (ich). T.A.P.

![D1A5 Starke Verben [Strong Verbs]](http://s1.studylibde.com/store/data/005537802_1-7c1b99dd5766654382e175dbf31adcce-300x300.png)