Nouns (das Nomen die Nomina) - FrauHarrill

Werbung

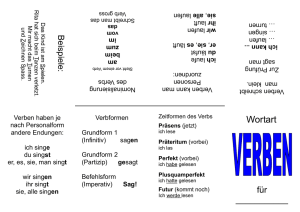

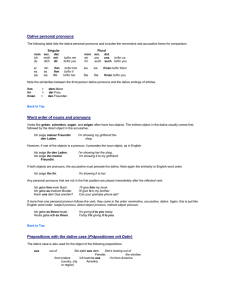

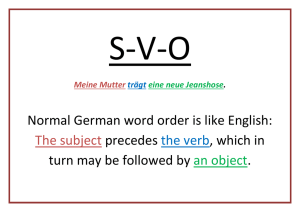

Grammatikunterricht 1 Nouns (das Nomen die Nomina) der Mann, das Buch, die Familie A noun is a person (eine Person), place (ein Ort), or thing (ein Ding). In German, all nouns are CAPITALIZED. Can you recognize the nouns in the following list? das Mädchen gehen der Garten kommen die Frau kennen das Auto Did you notice that German has 3 words for the when talking about the subject (nominative) in a sentence? (der/die/das) The der, die or das in front of the word is called the definite article. It means “the”. We refer to these as masculine (der), feminine (die) and neuter (das). Be aware, however, that the nouns associated with either of the three articles are not necessarily “masculine”or “feminine”or “neuter” by context—the article for a man’s tie (die Krawatte) is feminine, while a woman’s scarf (der Schal) is masculine. A good general rule for learning German vocabulary is to treat the article of a noun as an integral part of the word. Don't just learn Garten (garden), learn der Garten. Don't just learn Tür (door), learn die Tür. Not knowing a word's gender can lead to all sorts of other problems: das Tor is the gate or portal; der Tor is the fool. Are you meeting someone at the lake (der See) or by the sea (die See)? I will soon give you some hints that can help you remember the gender (der/die/das) of a German noun. The guidelines work for many noun categories, but certainly not for all. For most nouns you will just have to know the gender. (If you're going to guess, guess der. The highest percentage of German nouns are masculine.) Some of the following hints are a 100 percent sure thing, while others have exceptions. 1. das Mädchen 4. die Ecke 7. der Freund 10. der Herr 2. der Junge 5. der Tag 8. die Mutter (=mother) 11. das Foto 3. die Frau 6. die Minute 9. die Freundin 12.der Kuli Grammatikunterricht German Gender Hints Remember, always learn any new German noun with its gender (der/die/das)! But if you happen to forget the gender, you'll find the following hints for German gender helpful... Always MASCULINE (der/ein): Days, months, and seasons: Montag, September, Sommer Names of cars: der VW, der Mercedes. Words ending in -ismus: Journalismus, Kommunismus, Multikulturalismus Usually MASCULINE (der/ein): Most occupations and nationalities: der Architekt, der Lehrer, der Deutsche, der Schüler Note that the feminine form of these terms almost always ends in -in (die Architektin, die Lehrerin, die Schülerin, but die Deutsche). Nouns ending in -er, when referring to people (but die Mutter, die Schwester, die Tochter, das Fenster) Always FEMININE (die/eine): Nouns ending in the following suffixes: -heit, -keit, -tät, -ung, -schaft - Examples: die Freiheit, Universität, Umgebung, Freundschaft Cardinal numbers: eine Eins, eine Drei (a one, a three) Usually FEMININE (die/eine): Nouns ending in -in that pertain to female people, occupations, nationalities: Amerikanerin, Schülerin Most nouns ending in -e: Ecke, Minute, Karte, but der Deutsche, der Junge Nouns ending in -ei: Partei, Bäckerei (party [political], bakery), Always NEUTER (das/ein): Nouns ending in -chen or -lein: Büchlein, Mädchen (booklet, girl) Usually NEUTER (das/ein): Young animals and people: das Baby, das Kalb (calf); but der Junge (boy). Geographic place names (towns, countries, continents): das Berlin, Deutschland, Brasilien, Afrika (exceptions: der Irak, der Jemen, die Schweiz, die Türkei, die USA [plural]) Nouns ending in -o: das Auto, Kasino, Radio, Video Exceptions: die Avocado, die Disko, der Euro 2 Grammatikunterricht 3 The German Plural: die Mehrzahl One easy aspect of German nouns is the article used for noun plurals. All German nouns, regardless of gender, become die in the plural. A noun such as das Jahr (year) becomes die Jahre (years) in the plural. Sometimes the only way to recognize the plural form of a German noun is by the article: das Fenster (window) - die Fenster (windows). The following chart shows the dozen different ways that German nouns can form the plural (die Mehrzahl). Hint: Learning the noun plurals is a lot like learning gender (der/die/das). It is best to simply learn a noun with both its gender and its plural form. Although there are at least a dozen ways to form the plural in German, beginners should concentrate on the first five or six of the German plural forms listed below. More advanced learners should be aware of all of them. They are ranked here with the more common forms first: German Plural Formation Plural 1 Plural 2 Plural 3 Plural 4 Add an -e: der Freund – die Freunde Add an -en: die Minute – die Minuten No change: das Mädchen - die Mädchen Add an -n: die Tafel - die Tafeln Plural 5 Plural 6 Plural 7 Plural 8 Add ¨er or -er: das Buch - die Bücher Add an -s: das Auto - die Autos Stem vowel adds ¨:, der Bruder - die Brüder Add an -nen: die Freundin - die Freundinnen Plural 9 Plural 10 Plural 11 Plural 12 Add an -se: das Erlebnis - die Erlebnisse (experience) Add ¨e: der Plan – die Pläne Suffix/ending changes: das Museum - die Museen Foreign word plurals: das Prinzip – die Prinzipien (principle) Grammatikunterricht 4 It’s all about you: du, Sie, ihr du oder Sie? German has 3 words for “you”. When talking to one person, you will address him or her with du or Sie. How will you know which one to use? Woher kommen Sie, Herr Schulz? Wie alt bist du, Sophie? You = du is considered to be informal or familiar. It is what one family member calls another, an adult calls a child, or in prayers and church services. When people talk to animals, they use du. Blue-collar workers, students, and military personnel or police officers of equal rank use du. Young people use du to address each other. Close friends call each other du. You = Sie is considered to be formal, and is used among adults who are not close friends and also as a term of respect. Students address their teacher or Lehrer(in) with Sie, as do employees address their supervisor. When in doubt, address someone you do not know well with Sie. du oder ihr? Wo wohnt ihr, Tina und Marcus? Kennst du Maria, Marcus? As stated above, use du when you are talking to one person you know well, to relatives, to children or to animals. A plural form of du is ihr. While du is only used for one person, ihr is only used for two or more people. Note that Sie is used for adults and can be used to address one or more than one person. The word Sie is always capitalized Grammatikunterricht 5 Verbs: Verben What is a verb? (Was ist ein Verb?) Verbs are the action words in a sentence: (gehen, wohnen, sagen, singen, danken). Each verb has a basic "infinitive" ("to") form. This is the form of the verb you find in a German dictionary (spielen= to play, gehen= to go) Each verb has a "stem" form, the basic part of the verb left after you remove the -en ending. For spielen the stem is spiel- (spielen - en). To conjugate the verb—that is, use it in a sentence—you must add the correct ending to the stem. If you want to say "I play" you add an -e ending: "ich spiele" (which can also be translated into English as "I am playing"). Each "person" (he, you, they, etc.) requires its own ending on the verb. This is called "conjugating the verb." A regular verb like spielen is conjugated in the following manner: ich spiele SINGULAR I play du spielst you (fam.)play er spielt he plays sie spielt she plays es spielt it plays PLURAL Ich spiele Basketball. Spielst du Tennis? Er spielt Eishockey. Sie spielt Gitarre. wir spielen we play Wir spielen Baseball. ihr spielt you guys/y’all play Spielt ihr Monopoly? sie spielen they play Sie spielen Golf. Sie spielen you play Spielen Sie? (Sie, formal "you," is both singular and plural.) Es spielt keine Rolle. It doesn't matter. The Present Perfect (Perfekt) Tense (past tense) For the past tense (Present Perfect) of a regular verb, add “ge“ to the beginning of the stem and “t“ to the end. Place it at the end of the sentence and conjugate a form of haben in its place. Ich habe gespielt. Du hast gespielt. Er hat gespielt. Sie hat gespielt. Es hat gespielt. I played you (familiar)played he played she played it played Wir haben gespielt. Ihr habt gespielt. Sie haben gespielt. Sie haben gespielt. we played you guys/y’all played they played you played Grammatikunterricht Irregular Verbs: unregelmäßige Verben „ Sein oder Nichtsein, das ist die Frage.” I am ich bin we are wir sind you (informal) are du bist y’all are ihr seid he is/ she is/ it is You (formal) are Sie/sie sind they are er/sie/es ist Wir sind um drei Uhr zu Hause. Ihr seid klug! haben= to have I have ich habe we have wir haben you (informal) have du hast y’all have ihr habt he is/ she is/ it has er/sie/es hat You (formal)/they have Haben Sie Geschwister, Herr Schneider? Er hat zwei Brüder. werden= will (be) (future tense) ich werde wir werden du wirst ihr werdet er/sie/es wird Sie/sie werden Ich werde um drei Uhr nach Hause gehen. Wirst du eine Cola trinken? Sie/sie haben 6 Grammatikunterricht Irregular Verbs: unregelmäßige Verben, contd. wissen= to know (a fact) Pronoun Form Pronoun Form ich weiß wir wissen du weißt ihr wisst er/sie/es weiß Sie/sie wissen Helping Verbs (Modal Auxiliaries) to be permitted/ allowed to/ may to be able to/can to like to have to/must would like to to be supposed to/should to want to dürfen können mögen müssen möchten sollen wollen darf kann mag muss möchte soll will du darfst kannst magst musst möchtest sollst willst wir dürfen können mögen müssen möchten sollen wollen ihr dürft könnt mögt müsst möchtet sollt wollt dürfen können mögen müssen möchten sollen wollen ich er sie es Sie/sie Darf ich zur Toilette gehen? Magst du Bratwurst? Können Sie Klavier spielen, Frau Weber? 7 Grammatikunterricht 8 Irregular Verbs: unregelmäßige Verben, contd. Starke Verben (Verbs with Stem Vowel Change) A number of German verbs undergo a change in the stem vowel in the present tense. This only affects the second-person singular (DU) form and the third-person singular (ER, SIE, ES) forms. The other forms (ich, wir, ihr, Sie) act just like regular verbs, and in every person, the endings remain the same as for regular verbs. You cannot automatically know by seeing an infinitive (e.g. ‘sehen’); you’ll need to memorize which verbs belong to this class. 1. Vowel change from e › i ich du er/sie/es geben (to give) gebe wir gibst ihr gibt sie/Sie geben gebt geben ich du er/sie/es nehmen (to take) nehme wir nimmst ihr nimmt sie/Sie nehmen nehmt nehmen Verbs you need to know that follow this pattern (e › i) are: essen, geben, nehmen, sprechen, and treffen. Other verbs that you may encounter include: brechen (to break), helfen (to help), sterben (to die), werfen (to throw). 2. Vowel change from e › ie sehen (to see) ich sehe wir sehen du siehst ihr seht er/sie/es sieht sie/Sie sehen lesen (to read) ich lese wir lesen du liest ihr lest er/sie/es liest sie/Sie lesen Verbs you need to know that follow this pattern (e › ie) are: lesen and sehen (and its associated form fernsehen). Other verbs that you may encounter include: empfehlen (to recommend), geschehen (to happen), stehlen (to steal). 3. Vowel change from a › ä fahren (to drive) ich fahre wir fahren du fährst ihr fahrt er/sie/es fährt sie/Sie fahren laufen (to run) ich laufe wir laufen du läufst ihr lauft er/sie/es läuft sie/Sie laufen Verbs you need to know that follow this pattern (a › ä) are: anfangen, einladen, fahren, laufen, schlafen and tragen. Other verbs that you may encounter include: backen (to bake), fallen (to fall), lassen (to leave, to let), schlagen (to hit), waschen (to wash). Grammatikunterricht Verben mit trennbaren Vorsilben (Verbs with Separable Prefixes) As you know, German verbs can have separable prefixes. (anhaben) 1. These prefixes change the meaning of the original verb, and make a new word. (anhaben ≠ haben) 2. In the present tense, separable prefixes are separated from the verb and placed at the end of the sentence. (Ich habe ein T-Shirt an) 3. The dictionary form, or infinitive, (i.e. anhaben) is not divided, and when you use a helping (modal) verb (i.e. können) the verb will be at the end and not divided. Hans hat jeden Tag Jeans an. Hans wears Jeans every day. Hans, hab einen Anzug an! Hans, wear a suit! Im Winter muss Hans einen Mantel anhaben. Hans has to wear a coat in the winter. These are the verbs with separable prefixes you need to study!! anfangen to begin, start anhaben to have on, wear anrufen to call (on the phone) aufmachen to open einkaufen to shop einladen to invite fernsehen to watch television herkommen to come here losgehen to start mitbringen to bring along mitkommen to come along` rüberkommen to come over vorhaben to plan vorschlagen to suggest Which of these verbs are strong verbs? What categories do they belong to? 1. anfangen (fängt an, category 3) 2. einladen (lädt ein, category 3) 3. fernsehen (sieht fern, category 2) 4. vorschlagen (schlägt vor, category 3) Write sentences incorporating the words below. 1. Du rufst mich an. 2. Matthias darf mitkommen. 3. Tina schlägt eine Party vor. 4. Das Lacrossespiel geht um drei Uhr los. 5. Wir kaufen im Geschäft ein. 9 Grammatikunterricht 10 Irregular Verbs: unregelmäßige Verben, contd. Present Perfect Tense (Irregular Verbs) The irregular verbs, as the term suggests, do not follow the same pattern when forming the past participle as the regular verbs. Some of these verbs use sein instead of haben. Therefore, you must learn each past participle individually. Hast du mit Tanja gesprochen? Sie ist nach Hause gefahren. Have you spoken with Tanja? She has driven home. Verbs that use a form of sein must both (a) indicate motion or change of condition and (b) be intransitive, that is, verbs that cannot have a direct object. This is true in cases like sein, gehen, laufen, kommen, fahren, schwimmen, fliegen and bleiben. You will learn more like these!! Hast du schon mit Andrea gesprochen? Wir sind acht Stunden nach Europa geflogen. Have you spoken already with Andrea? We have flown for eight hours to Europe. Here are the irregular forms for most of the verbs you have learned so far: beginnen (to begin) begonnen bekommen (to receive, get) bekommen bleiben (to stay) ist geblieben bringen (to bring) gebracht einladen (to invite) eingeladen einsteigen (to get in, board) ist eingestiegen essen (to eat) gegessen fahren (to drive) ist gefahren finden (to find) gefunden fliegen (to fly) ist geflogen geben (to give) gegeben gefallen (to like) gefallen gehen (to go) ist gegangen haben (to have) gehabt helfen (to help) geholfen kennen (to know) gekannt kommen (to come) ist gekommen laufen (to run) ist gelaufen lesen (to read) gelesen liegen (to lie, be located) gelegen nehmen (to take) genommen scheinen (to shine) geschienen schießen (to shoot) geschossen schreiben (to write) geschrieben schreien (to scream, yell) geschrien schwimmen (to swim) ist geschwommen sehen (to see) gesehen sein (to be) ist gewesen singen (to sing) gesungen sitzen (to sit) gesessen sprechen (to speak) gesprochen stehen (to stand) gestanden tragen (to carry) getragen treffen (to meet) getroffen trinken (to drink) getrunken verlassen (to leave) verlassen vorschlagen (to suggest) vorgeschlagen wissen (to know) gewusst Verbs with separable prefixes have the ge- as part of the participle. Susi hat mich angerufen. Susi has called me. Wen habt ihr zur Party eingeladen? Whom have you invited to the party? Present Perfect Tense: Special Cases: The past participle of regular verbs with inseparable prefixes (like be-) is simply the er, sie, es form of the present tense. This is also true of verbs ending in -ieren. NOTE: Ich habe meine Freundin besucht. Grammatikunterricht 11 Simple Past (Narrative Past) Tense of Verbs: Imperfekt, Präteritum The narrative past tense is frequently used in narratives and stories.The past tense of regular verbs has the following endings added to the stem of the verb (notice ich & er/sie/es ARE THE SAME!) ich sag-te du sag-test er sag-te sie sag-te es sag-te wir sag-ten ihr sag-tet sie sag-ten Sie sag-ten Meine Lehrerin wohnte ein Jahr in Deutschland. My teacher lived in Germany for one year. When the stem of the verb ends in -t or -d, an -e- is inserted between the stem and the ending. Die Karte kostete nur ein paar Euro. The ticket cost just a few euros REVIEW p. 67 in your text for a list of some regular verbs. Irregular Verbs The irregular verbs do not follow the pattern of the regular verbs above and must be learned individually.To learn to use these verbs more easily you should study the first or the third person singular of the past tense.This will give you the base form to which endings are added in all other persons. Here are these endings: kommen ich kam du kam-st er/sie/es kam wir kam-en ihr kam-t Sie kam-en Viele Schüler kamen jeden Tag pünktlich. Jens ging um sieben Uhr zur Schule. Warum fuhrst du erst so spät in die Stadt? gehen ging ging-st ging ging-en ging-t ging-en fahren fuhr fuhr-st fuhr fuhr-en fuhr-t fuhr-en Many students came on time every day. Jens went to school at seven o’clock. Why did you drive downtown so late? To facilitate learning the correct use of the irregular verbs, you should always remember three forms: the infinitive, the past and the past participle.These forms are also called the “principal parts”of a verb.The most frequently used irregular verbs, which you already know, are listed on the next page. You will find the complete list of all irregular verbs in the “Grammar Summary”at the end of the textbook. Only the basic forms (without prefixes) of the more commonly used verbs are listed. Grammatikunterricht ei, ie, ie ei, i, i ie, o, o i, a, u i, a, o e, a, o e, a, e i, a, e a, u, a a, ie, a u, ie, u Irregular Mixed Simple Past (Narrative Past) Tense of Verbs: Imperfekt, Präteritum INFINITIVE IMPERFECT PAST PARTICIPLE MEANING bleiben blieb ist geblieben to stay schreiben schrieb geschrieben to write steigen stieg ist gestiegen to climb scheinen schien geschienen to shine schreien schrie geschrien to scream, yell schneiden schnitt geschnitten to cut fliegen flog ist geflogen to fly schießen schoss geschossen to shoot finden fand gefunden to find singen sang gesungen to sing trinken trank getrunken to drink beginnen begann begonnen to begin gewinnen gewann gewonnen to win schwimmen schwamm ist geschwommen to swim helfen half geholfen to help nehmen nahm genommen to take sprechen sprach gesprochen to speak treffen traf getroffen to meet essen aß gegessen to eat geben gab gegeben to give lesen las gelesen to read sehen sah gesehen to see sitzen saß gesessen to sit liegen lag gelegen to lie, be located fahren fuhr ist gefahren to drive schlagen schlug geschlagen to beat, hit tragen trug getragen to carry waschen wusch gewaschen to wash gefallen gefiel gefallen to like laufen lief ist gelaufen to run verlassen verließ verlassen to leave rufen rief gerufen to call gehen ging ist gegangen to go kommen kam ist gekommen to come sein war ist gewesen to be stehen stand gestanden to stand verstehen verstand verstanden to understand tun tat getan to do werden wurde ist geworden to become, be haben hatte gehabt to have kennen kannte gekannt to know wissen wusste gewusst to know bringen brachte gebracht to bring 12 Grammatikunterricht Wie kommst du dorthin? (How are you getting there?) Ich komme mit dem Bus zur Schule. Ich komme mit dem Rad zu meinem Freund. Ich komme mit der Straßenbahn in die Stadt. Did you notice that you change die to der? Did you notice that you change das or der to dem? Change die to der after mit or zu! Change das/der to dem after mit or zu! zum = zu dem zur = zu der German has 2 words for “to” that sometimes confuse students. zu or nach Use nach if you are going to another city, state, country or continent. Use zu if you are going most anywhere else. Note: Ich gehe in die Stadt. Ich fahre in die Schweiz/Türkei/Karibik. An important exception… 13 Grammatikunterricht zu/nach Hause Zu Hause means “at home” (location) and nach Hause means “(going) home” (motion). A key verb to help you remember nach Hause is gehen A key verb to help you remember zu Hause is sein Note that if you want to say "to my house/place" in German, you say zu mir dative pronoun) and the word Haus is not used at all! Note that if you want to say "at my house/place" in German, you say bei mir (bei + dative pronoun) and the word Haus is not used at all! Wo ist Heidi? Sie ist zu Hause. Where is Heidi? She is at home. Wohin geht Uwe? Er geht nach Hause. Where is Uwe going? He is going home. Kommst du später zu mir rüber? Nein, am Abend ist mein Cousin bei mir. Are you coming over later to my place? No, my cousin will be at our house tonight. Sind sie zu Hause oder gehen sie nach Hause? Complete the following sentences using the words zu or nach. 1. Ist Werner zu Hause? 2. Um wie viel Uhr kommst du 3. Ich höre gern CDs zu nach Hause? Hause. 4. Später spielen wir Karten zu Hause. 5. Wir gehen gleich nach Hause. 6. Gehst du jetzt nach Hause? 7. Heike ist heute schon um drei Uhr 8. Frau Schubert ist zu zu Hause am Telefon. 9. Mein Hund wohnt bei mir zu 10. Ich muss nach Hause. (zu + Hause. Hause. 14 Grammatikunterricht 15 Nominative and Accusative Case (Kasus: Nominativ und Akkusativ) What is the subject of a sentence? The subject of a sentence is the person or thing that is “doing” the verb. To find the subject, look for the verb and ask “Who or what is doing?” (substitute the verb for “doing” -- Who or what is singing? Who or what is sleeping?) Subjects are always in the NOMINATIVE CASE. What is the direct object of a sentence? The direct object receives the action of the verb. To find the direct object, look for the verb and ask “Who or what is being verbed?” (as in Who or what is being kicked? Who or what is being read?) Direct objects take the ACCUSATIVE CASE. 1. The Definite Article = THE (changing der to den) Kaufst du den Bleistift? Are you buying the pencil? Brauchst du den Kuli? Do you need the pen? In the questions above, du is the subject (nominative), kaufst/brauchst the verb and den Bleistift / den Kuli the direct object (accusative) of the sentence. Compare the statements below: Ich höre die Musik. I am listening to the music. ich is the subject (nominative), höre the verb and die Musik the direct object (accusative). Wir lesen das Buch. We are reading the book. wir is the subject (nominative), lesen the verb and das Buch the direct object (accusative). Some English Examples: The woman sees the girl. The woman is the subject and is nominative. the girl is the direct object and is accusative. The girl sees the woman. The girl is the subject and is nominative. the woman is the direct object and is accusative. My brother is David. my brother is the subject and is nominative. David is ALSO nominative because it follows “to be” (is). 2. The Indefinite Article = A/An (changing ein to einen) In English the articles “the”, “a” and “an” do not change depending on whether the noun is accusative or nominative. (Only pronouns change case in English: compare “She sees me” and “I see her”.) In German not only the personal pronouns but also many other words change their form based on case. The articles (der, ein, kein, etc.), possessive adjectives (mein, dein, etc.), and a few (unusual) nouns all change their form (usually by adding or changing endings) depending on what case they are in. Right now we’ll be dealing mostly with the definite articles (der/die/das) and the indefinite articles (ein/eine); the table on the next page shows how they change in the accusative case: Grammatikunterricht 16 Nominative and Accusative Case (Kasus: Nominativ und Akkusativ), contd. Nominative Definite Indefinite Masc. Der Tisch ist braun. Das ist ein Tisch. Fem. Die Landkarte ist neu. Das ist eine Landkarte. Neut. Das Buch ist offen. Das ist ein Buch. Plural Die Bücher sind interessant. Das sind keine Bücher. All of the nouns above are in the nominative case because they are the subjects of the sentences or because they follow the verb “sein.” Accusative Definite Masc. Ich sehe den Tisch. Fem. Ich sehe die Landkarte. Neut. Ich sehe das Buch. Plural Ich sehe die Bücher. Indefinite Ich habe einen Tisch. Ich habe eine Landkarte. Ich habe ein Buch. Ich habe keine Bücher. The nouns above are all in the accusative case because they are direct objects. To summarize in a few words: Nominative case is used: Accusative case is used: - for the subjects of sentences - for direct objects - after any form of the verb “to be” - after accusative prepositions A. Practice. Circle all nouns in the nominative, and underline all nouns in the accusative. 1. I meet them on Tuesday. 2. They invited me. 3. Paul hit the ball. 4. Martin and Petra like to read. 5. Have you seen a Shakespeare play? 6. He plays the piano. 7. “The Lives of Others” is a German movie. 8. I’m sleeping. 9. Is that a Mercedes? 10. He owns a house and a car. B. Auf Deutsch. Now practice identifying subjects and objects in these German sentences. 1. Er hat ein Buch. 2. Ich trinke Kaffee. 3. Martin und Georg kaufen viele CDs. 4. Peter hat den Bleistift. 5. Herr Schmidt trinkt eine Cola und ein Glas Subjekt = er Objekt =ein Buch Subjekt = ich Objekt =Kaffee 6. Meine Großeltern sprechen deutsch. Subjekt = meine Großeltern Objekt =deutsch Subjekt = Martin und Georg Objekt =viele CDs Subjekt = Peter Objekt =den Bleistift Subjekt = Herr Schmidt Objekt =eine Cola und ein Glas Wasser Wasser. Grammatikunterricht 17 Nominative and Accusative Case (Kasus: Nominativ und Akkusativ), contd. C. Sie sind dran. It’s your turn! Now that you’ve had some practice recognizing forms, what about writing them yourselves? Fill in the blanks with the correct form of the articles in parentheses. First, figure out what word is subject and what is object; then think about what the right form is. Fill in the correct DEFINITE article (der/die/das/den). 1. Der Vater findet die Tür nicht. 2. Die Lehrerin schreibt den Brief (=letter, m). 3. Hat der Bruder das Buch? 4. Er hat das Buch und den Bleistift. 5. Die Frau kauft den Kuli, die Landkarte und das Telefon. 6. Das ist der Mann! 7. Ich sehe das Buch, die Tür und das Lineal auf dem Tisch. 8. Das Klassenzimmer (n.) ist sehr groß. 9. Die Bücher sind klein. 10. Wo sind die Kinder (pl)? 11. Wo ist der Tisch? 12. Ich sehe den Tisch. 13. Wir hören die Schülerinnen (pl). 14. Die Mutter lernt englisch. 15. Herr und Frau Schmidt verstehen den Sohn und die Tochter nicht. Fill in the correct INDEFINITE article (ein/eine/einen). 1. Ein Mann kommt ins Klassenzimmer. 2. Hast du einen Bruder oder eine Schwester? 3. Ein Stuhl ist kaputt. 4. Hast du einen Stuhl? 5. Ich suche einen Stuhl und eine Schultasche. 6. Meine Schwester und ich sehen einen Freund und eine Freundin in der Schule. 7. Heute kommt ein Cousin von mir (=of mine). 8. Eine Schülerin heißt Karin und ein Schüler heißt Karl. Fill in the correct form of kein. 1. Das ist kein Mann -- das ist eine Frau! 2. Das ist kein Problem (n). 3. Wir haben keine Zeit (=time, f). 4. Hier ist keine Uhr. 5. Sie hat keine Tafel, keinen Stuhl und kein Buch. Grammatikunterricht Nominative and Accusative Case (Kasus: Nominativ und Akkusativ), contd. der/die/das ODER den??? Find the gender of the word. Does the word take der? Does the word take die? Does the word take das? der die das Is the word being “verbed”? Is the word doing the verb? no change change der den ein/eine ODER einen??? Find the gender of the word. Does the word take der? Does the word take die? Does the word take das? der ein Is the word doing the verb? die das eine ein Is the word being “verbed”? no change ein change einen 18 Grammatikunterricht 19 Dative Case (der Dativfall) He is coming by bike. Er kommt mit dem Rad. I am buying my friend a ticket. Ich kaufe meinem Freund eine Karte. The woman does not like the film. (= The film is not pleasing to the woman.) Der Film gefällt der Frau nicht. Did you notice how...? 1. das Rad became dem Rad 2. mein Freund became meinem Freund 3. die Frau became der Frau That is the Dative Case! There are three reasons for using the dative case… 1. after a dative preposition 2. for the indirect object in a question or a sentence 3. after a dative verb We will focus on Number One(= dative prepositions) first. aus..........................out of, from nach................................after, to außer.................except for, besides seit................................since bei........................at, near, with von.................................from, by mit..................................with zu..................................to One memory aid for these prepositions is to sing the Blue Danube Waltz melody with the prepositions: aus-außer-bei-mit-nach-seit-von-zu. Beispiele: Sie haben ein Geschenk von ihrem Vater bekommen. From their father. Außer meiner Mutter spricht meine ganze Familie Deutsch. Except for my mother. Ich fahre am Wochenende zu meiner Tante in Minnesota. To my aunt's. Grammatikunterricht 20 Dative Case, continued Two notes on using the dative with prepositions. First off, there are several contractions that occur with dative prepositions. They are: vom = von dem zum = zu dem beim = bei dem zur = zu der Also, as we have talked about, the preposition “in” often uses the dative case. Later you will be learning more about this preposition and how to use it correctly. For now, the most you need to know is that when ‘in’ is used with a stationary verb (e.g. He’s in the house), it takes the dative case. Like the contractions above, im = in dem. Der Tisch steht in der Küche. Mein Schreibtisch ist im Arbeitszimmer. Die Autos sind in den Garagen. Where is it? In the kitchen. Note that im = in dem The cars are in the garages, plural. SO HOW DOES THIS WORK? der die das dem der dem die (pl.) ein eine ein CHANGE IN THE DATIVE TO…. den +n einem einer einem keine (pl) keinen +n The only irregularity in the dative case: dative PLURAL forms add an -n to the noun if at all possible. Consider: den Freunden (adds -n to plural form Freunde) den Amerikanern (adds -n to plural form Amerikaner) den Leuten (adds -n to plural form Leute) mit den Eltern (already had an -n for plural, no second -n added) den Frauen (already had an -n for plural, no second -n added) den Cousins (had an -s for plural, but Cousinsn not possible!) I you he she it NOM ich du er sie es DAT mir dir ihm ihr ihm we you all they You NOM wir ihr sie Sie DAT uns euch ihnen Ihnen Grammatikunterricht 21 Dative Case, continued A primary use of the dative case is for the indirect object of a sentence. An indirect object is the beneficiary of whatever happens in a sentence. It’s usually a person, although it doesn’t have to be. If you ask yourself: “TO whom or FOR whom is this being done?”, the answer will be the indirect object, and in German it will need the dative case. Not every sentence will have an indirect object -- Like in English, only some verbs allow an indirect object: to give (to), to bring (to), to tell (to), to buy (for), to send (to) are some good examples of verbs that will almost always have an indirect object. In English, we don't distinguish the direct and indirect object in the forms of words; instead, we often use "to" or "for" to mark these. If you can potentially insert "to" or "for" in front of a noun in an English sentence, it's probably an indirect object. Ich gebe der Frau ein Buch. Er schenkt mir ein Buch. Ich habe das dem Mann schon gesagt. Wir kaufen unserer Mutter ein Geschenk. I’m giving her a book = a book to her. He's giving me a book. I already told the man that. We're buying our mother a present. Let’s practice identifying objects in some sentences first. Tell whether the underlined nouns/pronouns in these sentences are SUBJECTS (S), DIRECT OBJECTS (DO), or INDIRECT OBJECTS (IO). 1. The salesman offered the customer the car. 2. We’re bringing her the mail. 3. I lent my stereo to you. 4. He promised his wife everything. 5. The realtor sold the house to us. 6. For my dog, I’m buying a chew-toy. Now do the same thing, but with these German sentences. 1. Ich gebe ihm ein Auto. 2. Die Schwester hat ihrem Lehrer die Antwort gesagt. 3. Der Sohn gibt seiner Mutter eine Blume. 4. Kannst du uns dein Auto leihen (=to lend)? 5. Euch gebe ich jetzt das Quiz. 6. Die Fotos habe ich meinen Freunden gezeigt (=showed). Grammatikunterricht 22 Dative Case, continued Verbs Followed by the Dative Case There are a number of verbs in German that require the dative case. Contained in these verbs is the idea of “TO OR FOR” (= INDIRECT OBJECT) Here are some verbs that take the dative case: gefallen to like, to be pleasing to glauben to believe (to offer belief to) helfen to help (to offer help to) Leid tun to be sorry (for an offending action) passen to fit, suit (to be the right size for) schmecken to taste (to someone) stehen to suit (to look good on) wehtun to hurt (to be painful to) Das Sweatshirt passt deiner Schwester sehr gut. The sweatshirt fits your sister very well. Kannst du deinem Vater helfen? Can you help your father? Das tut mir Leid! I am sorry! Remember that gefallen (gefällst, gefällt) and helfen (hilfst, hilft) are STRONG VERBS!! Grammatikunterricht 23 Comparing adjectives and adverbs To form the comparative for most adjectives or adverbs in German you simply add -er, as in neu/neuer (new/newer) or klein/kleiner (small/smaller). For the superlative, English uses the -est ending, the same as in German except that German often drops the e and usually adds an adjective ending: (der) neueste (the newest) or (das) kleinste (the smallest). Unlike English, however, German never uses "more" (mehr) with another modifier to form the comparative. In English something may be "more beautiful" or someone could be "more intelligent." But in German these are both expressed with the -er ending: schöner and intelligenter. German also has some irregular comparisons, just as English does. Sometimes these irregular forms are quite similar to those in English. Compare, for instance, the English good/better/best with the German gut/besser/am besten. On the other hand, high/higher/highest is hoch/höher/am höchsten in German. But there are only a few of these irregular forms, and they are easy to learn, as you can see below. Irregular Adjective/Adverb Comparison POSITIVE COMPARATIVE SUPERLATIVE gern (gladly) lieber (more gladly) am liebsten (most gladly) groß (big) größer (bigger) am größten (biggest) der/die/das größte gut (good) besser (better) am besten (best) der/die/das beste hoch (high) höher (higher) am höchsten (highest) der/die/das höchste nah (near) näher (nearer) am nächsten (nearest) der/die/das nächste viel (much) mehr (more) am meisten (most) die meisten When adjectives end in d, t, s, ß, sch, st, x or z, the ending in the superlative has an additional e, with the exception of größer, am größten. Die Rockmusik ist am interessantesten. The rock music is the most interesting. Im Sommer ist es am heißesten. It is the hottest during the summer. Grammatikunterricht 24 Comparatives and Superlatives, contd. There is one more irregularity that affects both the comparative and superlative of many German adjectives and adverbs: the added umlaut ( ¨ ) over a, o, or u in most one-syllable adjectives/adverbs. Below are some examples of this kind of comparison. Exceptions (do not add an umlaut) include bunt (colorful), falsch (wrong), froh (happy), klar (clear), laut (loud), and toll (great). Irregular Comparison - Umlaut Added POSITIVE COMPARATIVE SUPERLATIVE dumm (dumb) dümmer (dumber) am dümmsten (dumbest) der/die/das dümmste kalt (cold) kälter (colder) am kältesten* (coldest) der/die/das kälteste* *Note the "connecting" e in the superlative: kälteste klug (smart) klüger (smarter) am klügsten (smartest) der/die/das klügste lang (long) länger (longer) am längsten (longest) der/die/das längste stark (strong) stärker (stronger) am stärksten (strongest) der/die/das stärkste warm (warm) wärmer (warmer) am wärmsten (warmest) der/die/das wärmste In order to use the comparative forms above and to express relative comparisons or equality/inequality ("as good as" or "not as tall as") in German, you also need to know the following phrases and formulations using als, so-wie, or je-desto: mehr/größer/besser als = more/bigger/better than (nicht) so viel/groß/gut wie = (not) as much/big/good as je größer desto besser = the bigger/taller the better Grammatikunterricht 25 Comparatives and Superlatives, contd. ENGLISH DEUTSCH My sister is not as tall as I am. Meine Schwester ist nicht so groß wie ich. His Audi is much more expensive than my VW. Sein Audi ist viel teurer als mein VW. We prefer to travel by train. Wir fahren lieber mit der Bahn. Karl is the oldest. Karl is oldest. Karl ist der Älteste. Karl ist am ältesten. The more people, the better. Je mehr Leute, desto besser. He likes to play basketball, but most of all he likes to play soccer. Er spielt gern Basketball, aber am liebsten spielt er Fußball. The ICE [train] travels/goes the fastest. Der ICE fährt am schnellsten. Most people don't drive as fast as he does. Die meisten Leute fahren nicht so schnell wie er. Grammatikunterricht 26 German Word Order, When Subjects Are Not First: Wortstellung mit Zeitangaben You’ve already learned many ways to express the time and day in German -- for instance, ‘am Freitag’ or ‘um 8 Uhr’. Let’s expand what you know by looking at some time expressions. GERMAN TIME EXPRESSIONS= ZEITANGABEN heute = today diese Woche = this week morgen = tomorrow am Wochenende = on the weekend gestern = yesterday dieses Jahr = this year übermorgen = the day after tomorrow nächstes Jahr = next year heute Abend = this evening vor einem Jahr = a year ago diesen Freitag = this Friday im Jahre 2008 = in the year 2008 VARIOUS UNITS OF TIME IN GERMAN= ZEITEINHEITEN die Minute, -n = minute die Woche, -n = week die Stunde, -n = hour das Wochenende, -n = weekend der Tag, -e = day der Monat, -e = month die Nacht, -¨e = night das Jahr, -e = year Generally speaking, German sentences follow the rule of TIME-MANNER-PLACE (WANN-WIE-WO). Time elements occur before manner elements (how you do something, e.g. by car, with friends, happily), and the place or destination occurs last of the three. This is different from English, so you’ll need to get used to saying the time before the place. Also, general time (days) comes before specific time (2:00), which is the same as English (‘today at 5:00’ = heute um 5 Uhr). Susi kommt heute um 8 Uhr mit dem Bus in die Schule. Lars kommt am Mittwoch um 2 Uhr mit seinen Freunden nach Hause. German word order is slightly flexible: time elements can be moved to the front of the sentence. Unlike English, there is NO COMMA used when a time element occurs first in a German sentence. Also, remember that the conjugated VERB in a German sentence is NOT moveable, and needs to be the SECOND element in the sentence. (An element can be comprised of more than one word, e.g. ‘heute Morgen’ is one element.) When you start a sentence with something other than the subject, then the subject must immediately follow the verb (e.g. Morgen gehe ich ...). As long as you keep the verb in second position, and follow the secondary rule of time-manner-place, you can move many elements in a sentence around. Tina kommt heute Morgen mit ihren Eltern in die Schule. Heute Morgen kommt Tina mit ihren Eltern in die Schule. Grammatikunterricht 27 German Word Order, When Subjects Are Not First: Wortstellung mit Zeitangaben, contd. So just to review: VERB 2nd TIME MANNER PLACE Sie kommt heute um 8 Uhr Heute kommt sie um 8 Uhr Um 8 Uhr kommt sie heute mit dem zur Schule. Bus mit dem zur Schule. Bus mit dem zur Schule. Bus (normal word order) (normal word order, stressing ‘today’ slightly) (unusual: this emphasizes ‘8:00’ as important) ALSO POSSIBLE: Zur Schule kommt sie heute mit dem Bus um 8 Uhr. (unusual: this stresses “to school”) Sei kreativ! Be creative! Let’s practice. I. Create 4 sentences using the words below, beginning with the subject. USE TIME-MANNER- PLACE (WANN-WIE-WO) AND ALWAYS PUT YOUR VERB 2nd! SUBJEKT WO? was? WANN? WIE? der Mann meine Mutter Harry Potter die Lehrerin die Band im Klassenzimmer im Café Julia zu Hause in dem Kaufhaus auf einer Party trinkt Kaffee spielt Rugby hört Musik lernt spanisch singt einen Song am Freitag im November später morgen um 8 Uhr schnell zum Spaß (=for fun) schlecht gern mit meinen Freunden 1. 2. 3. 4. Meine Mutter trinkt Kaffee um 8 Uhr schnell zu Hause. Harry Potter spielt Karten am Freitag mit meinen Freunden im Café Julia. Der Mann lernt spanisch morgen schnell in dem Kaufhaus. Die Lehrerin singt einen Song im November gern auf einer Party. CONTINUED ON NEXT PAGE Grammatikunterricht 28 German Word Order, When Subjects Are Not First: Wortstellung mit Zeitangaben, contd. II. Create 4 sentences, beginning with words other than the subject. ALWAYS PUT YOUR VERB 2nd! YOUR SUBJECT WILL FOLLOW THE VERB. 1. 2. 3. 4. SUBJEKT WO? was? WANN? der Mann meine Mutter Harry Potter die Lehrerin die Band im Klassenzimmer im Café Julia zu Hause in dem Kaufhaus auf einer Party trinkt Kaffee spielt Rugby hört Musik lernt spanisch singt einen Song am Freitag im November später morgen um 8 Uhr Um 8 Uhr trinkt meine Mutter Kaffee zu Hause. Am Freitag spielt Harry Potter Karten im Café Julia. Morgen lernt der Mann spanisch in dem Kaufhaus. Auf einer Party singt die Lehrerin einen Song gern. CLOSING THOUGHTS Where does the verb go in a German sentence? It is always in the second place. How is German word order different than English? It follows stricter rules: verb 2nd , time-manner-place (WANN-WIE-WO). It is more flexible than English: sentences can often start with words other than the subject. Grammatikunterricht 29 die Pronomen: German Pronouns You have already learned the accusative case with definite and indefinite articles (den, einen). You have also learned personal pronouns in the nominative case (ich, du, er, etc). Now it’s time to learn the same pronouns in the accusative case. They are: NOM ENG AKK ENG NOM ENG AKK ENG ich I mich me wir we uns us du you dich you ihr y’all euch you all er he ihn him sie they sie them sie she sie her Sie You (f.) Sie You (f.) es it es it the pronouns for ‘me’ (mich) and ‘us’ (uns) are very much like English, so they shouldn’t be a problem. The pronouns for ‘him’, ‘her’, ‘it’ and ‘them’ follow the same pattern as the articles: der (er) becomes den (ihn); die (sie) stays die (sie), and das (es) stays das (es). That leaves the plural you form (ihr - euch), which you’ll just need to memorize! When to use the accusative case, as a reminder: direct objects in a sentence must be in the accusative case. Siehst du den Mann? -- Ja, ich sehe ihn. Hast du das Buch? -- Ja, ich habe es. Kennst du mich? -- Ja, ich kenne dich. Note: please do not confuse these pronouns with the possessive adjectives (his, her, my, your) that we just learned. Those words (mein, dein, sein) are just like the article ein: (m)eine Mutter. The accusative pronouns, however, stand alone as a substitute for a noun, just like in English: I see them = Ich sehe sie. Grammatikunterricht 30 die Pronomen: German Pronouns A. Decide whether the underlined pronoun is in the nominative or accusative case. 1. Michael fragt ihn. (AKK ) 2. Kennst du sie? (AKK ) 3. Sie hat es. ( NOM) 4. Er hat sie gern. (AKK ) 5. Wer spielt es? (AKK ) 6. Wann fängt es an? ( NOM) anfangen= to begin 7. Wo finde ich ihn? (AKK ) 8. Sieht er sie? ( NOM) B. Restate the sentences using a pronoun instead of the underlined noun. Write the correct pronoun in the blank. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. Wir hören es. Ich sehe ihn. Besucht ihr sie? Ich frage sie. Ich rufe sie an. Ich höre ihn. Er hat es. Hast du ihn? anrufen=to call on the phone C. Provide the pronouns for the underlined nouns in the answering statement. 1. 2. 3. 4. Ja, wir sehen ihn. Ja, ich möchte ihn fragen. Nein, wir verstehen sie nicht. Dort ist sie! D. Supply the proper personal pronoun in German for those in parentheses. 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. Kann ich Sie etwas fragen, Herr Peters? Wir sehen sie im Klassenzimmer. Kennt ihr ihn nicht? Warum könnt ihr mich nicht verstehen? Fragen Sie uns bitte! Ich kann dich/Sie schon sehen, Jörg. Sie besucht euch bald, Petra und Andrea. Grammatikunterricht Reflexive Verben: Reflexive Verbs Ich freue mich auf die Reise. I’m looking forward to the trip. (sich freuen auf= to look forward to) Wir müssen uns beeilen. We’ll have to hurry. (sich beeilen= to hurry) In German, reflexive verbs are usually identified (in a dictionary) by the reflexive pronoun sich preceding the infinitive form. Contrary to English verbs, many German verbs are always used with a reflexive pronoun and, therefore, are called “reflexive verbs.” The reflexive pronoun sich is similar to the English “oneself.” Did you notice that you will change the word sich to words like mich (if you are talking about “myself”) and uns (if you are talking about “ourselves”)? The reflexive pronoun refers to a person who is both the subject and the object of the sentence. Compare the following: Ich wasche das Auto. Ich wasche mich. NOT REFLEXIVE: I’m washing the car. REFLEXIVE: I’m washing myself. Here are the reflexive verbs you have learned/are learning so far: sich ansehen*1 to look at sich beeilen to hurry sich duschen to shower, take a shower sich freuen auf to look forward to sich kämmen to comb one’s hair sich putzen to clean oneself sich rasieren to shave oneself sich setzen to sit down sich treffen* to meet sich vorbereiten1 to prepare sich waschen* to wash oneself * STRONG VERB 1 SEPERABLE PREFIX VERB Übersetze ins Deutsche (translate into German): 1. Erika is hurrying up today. = Erika beeilt sich heute. 2. Thomas is looking at the map. = Thomas sieht sich die Landkarte an. 3. Angelika is meeting with friends. =Angelika trifft sich mit Freunden. 31 Grammatikunterricht 32 Reflexivpronomen: Reflexive Pronouns When a reflexive pronoun is used as a direct object, it appears in the accusative case. sich kämmen ich kämme mich du kämmst dich er/sie/es kämmt sich wir kämmen uns ihr kämmt euch sie (pl) kämmen sich Sie kämmen sich sich waschen wasche mich wäschst dich wäscht sich waschen uns wascht euch waschen sich waschen sich The reflexive pronoun appears in the dative case when it functions as an indirect object. The dative reflexive pronoun refers to both the subject and the indirect object of the sentence. Quite often, the direct object is a body part or piece of clothing that belongs to the subject. sich kämmen to comb one’s own hair Ich kämme mir die Haare. I’m combing my hair. sich putzen to clean oneself Ich putze mir die Zähne. I’m brushing (cleaning) my teeth. When you’re trying to decide whether to use an accusative or dative reflexive pronoun, look at the sentence and determine if there is another element (such as a body part) that is acting as the direct object. If so, then the reflexive pronoun will be dative (the indirect object). Otherwise, if there is no other element in the sentence, the reflexive pronoun must be accusative. The following is a chart of the accusative and dative reflexive pronouns in German. Notice that for the most part, these pronouns are the same as the object pronouns (dich, uns, etc.). Only the third-person forms (sich) are new to you. Also notice that the only differences between dative and accusative forms are in the first (mich-mir) and second (du-dir) singular persons. NOM AKK ich........... mich.......... mir du........... dich........... dir er............ sich........... sich sie........... sich........... sich es............ sich........... sich DAT NOM AKK wir............ uns.............. uns ihr............ euch............ euch sie............ sich............. sich Sie............ sich............. sich DAT Grammatikunterricht 33 Die Pronomen und die Fälle: German Pronouns and Cases Ich habe einen neuen Computer. I have a new computer. Ja? Wo hast du ihn gekauft? Yeah? Where did you buy it? Wer ist das? Sophies Sohn. Ihn kennst du nicht? Who is that? Sophie’s son. Don’t you know him? When "he" changes to "him" in English, that's exactly the same thing that happens when der changes to den in German (and er changes to ihn). Note that German has many words for it. Definite Articles (the) Fall Case Männlich Masculine Weiblich Feminine Sächlich Neuter Mehrzahl Plural Nominativ (subject) der die das die Akkusativ (dir. obj.) den die das die Dativ (indir. obj.) dem der dem den +n Genitiv (possess.) des+s der des+s der Indefinite Articles (a/an) Fall Männlich Weiblich Sächlich Mehrzahl Nom ein eine ein keine Akk einen eine ein keine Dat einem einer einem keinen +n Gen eines+s einer eines+s keiner Third-Person Pronouns (er, sie, es) Fall Männlich Weiblich Sächlich Mehrzahl Nom er he sie she es it sie they Akk ihn him sie her es it sie them Dat ihm (to) him ihr (to) her ihm (to) it ihnen (to) them Gen sein his ihr her sein its ihre their Demonstrative Pronouns (der, die, denen) Fall Männlich Weiblich Sächlich Mehrzahl Nom der that one die that one das that one die these Akk den that one die that one das that one die those Dat dem (to) that der (to) that dem (to) that denen (to) them Gen dessen of that deren of that dessen of that deren of them Grammatikunterricht Other Pronouns Fall Case 1. Person sing. 1. Person plur. 2. Person sing. 2. Person plur. Nom ich I wir we du you ihr you Akk mich me uns us dich you euch you Dat mir (to) me uns (to) us dir (to) you euch (to) you Gen* (Poss.) mein my unser our dein your euer your Interrogative "who" • Formal "you" Fall Case Wer? who? 2. Person formal (sing. & plur.) Nom wer Sie Akk wen whom Sie you Dat wem (to) whom Ihnen (to) you Gen* (Poss.) wessen whose Ihr your Let’s work the cases! Translate into German. Q: Where is my sleeping bag? Wo ist mein Schlafsack? A: I have not seen it! Ich habe ihn nicht gesehen? Q: To whom did you give the groceries? Wem hast die Lebensmittel gegeben? A: To our brother. Zu unserem Bruder. Q: She is bringing the computer. Sie bringt den Computer. A: Is it new? Ist er neu? Q: Is he going with his friends? Geht er mit seinen Freunden? A: No, he is staying in the restaurant. Nein, er bleibt in dem Restaurant. 34 Grammatikunterricht 35 Word Order of Dative and Accusative Cases Er zeigt dem Herbergsvater seine Mitgliedskarte. Er zeigt ihm seine Mitgliedskarte. Er zeigt sie dem Herbergsvater. Er zeigt sie ihm. 1-The following word order should be familiar to you: In a sentence containing both an indirect object noun (dat.) and a direct object noun (acc.), the indirect object noun precedes the direct object noun. Er zeigt He shows Indirect Object Noun (dative) dem Herbergsvater (to) the hostel director Direct Object Noun (accusative) seine Mitgliedskarte. his membership card. . 2-Let’s use a pronoun to substitute for dem Herbergsvater. When the indirect object or the direct object appears as a pronoun, the pronoun precedes the noun object. Er zeigt He shows Ind. Obj. Pronoun (dative) Dir. Obj. Noun (acc.) ihm (to) him seine Mitgliedskarte. his membership card. 3-Now let’s use a pronoun to substitute for seine Mitgliedskarte. Er zeigt He shows Dir. Obj.Pronoun (acc) sie it Ind. Ob. Noun (dative) dem Herbergsvater (to) the hostel director 3-Finally, let’s pronouns to substitute for ihm AND seine Mitgliedskarte. Er zeigt He shows Dir. Obj.Pronoun (acc) sie it Ind. Ob. Noun (dative) ihm (to) him A helpful hint: If the direct object is a noun, it is second. If the direct object is a pronoun, it is first. Grammatikunterricht 36 Der Genitiv (The Genitive Case) The genitive case is used in German to express either: • possession, ownership, belonging to or with: Hier ist das Auto meines Vaters. Hast du die Freunde meiner Schwester gesehen? Here is my father’s car. Did you see my sister’s friends? • “of” in English, when referring to a part or component of something else: Am Anfang des Jahres haben wir viel gelernt. Der Titel des Buches ist Der Zauberberg. We learned a lot at the beginning of the year. The title of the book ist Der Zauberberg. • in addition, there are a handful of prepositions that require the genitive case: anstatt (statt) -- instead of: Anstatt eines Wagens haben sie ein Motorrad gekauft. Instead of a car they bought a motorcycle. trotz -- in spite of: Ich gehe zur Party trotz meiner Erkältung. I’m going to the party in spite of my cold. während -- during, in the course of: Während der Party haben wir viel gegessen. During the party we ate a lot. wegen -- because of: Wir sind wegen des Wetters zu Hause geblieben. We stayed at home because of the weather. Remember RESE NESE MRMN? This is a new line: SRSR (= des der des der) The genitive case is unusual in German because it adds an ending not only to the articles, but to masculine and neuter nouns as well. This ending is -es for single-syllable masculine and neuter nouns. When the noun is more than one syllable long, the ending is usually just -s. masc des Mannes meines Mannes neut des Buches meines Buches fem der Frau meiner Frau pl der Blumen meiner Blumen In addition, you may see the question word wessen: this is merely the genitive form of wer, and means “whose”. It never has any other form or endings: Wessen Auto ist das? Whose car is that? Wessen Bücher liegen hier? Whose books are lying here? Remember that with personal names, you can simply add an -s to indicate the possessive (Heidis Freund, Ingos Katze, etc.) Grammatikunterricht 37