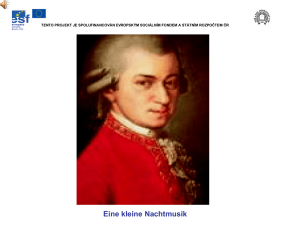

wolfgang amadeus mozart eine kleine nachtmusik kv 525

Werbung

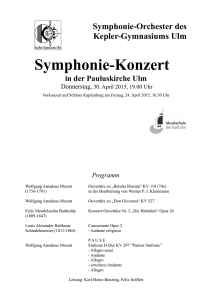

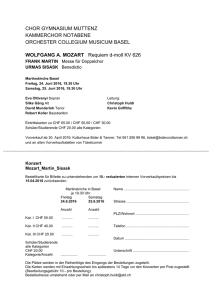

wolfgang amadeus mozart eine kleine nachtmusik k v 525 introduction · einführung wolfgang rehm bä r e n r e it e r fac s i m i l e kassel · basel · London · New York · Praha Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 3 27.02.2013 11:15:31 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data is available in the internet at http://d-nb.de. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://d-nb.de abrufbar. © 2013 Bärenreiter-Verlag Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG, Kassel Illustrations cover and pp. 9 and 17 · Abbildungen Cover und S. 9 und 17: © The British Library Board Illustration p. 24 · Abbildung S. 24: © Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum (ISM), Bibliotheca Mozartiana Design · Innengestaltung: Dorothea Willerding Typeset · Satz: Christina Eiling, edv + Grafik, Kaufungen Printed by · Druck: Werbedruck Schreckhase GmbH, Spangenberg Bound by · Bindung: Beltz Bad Langensalza GmbH, Bad Langensalza ISBN 978-3-7618-2282-1 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 4 27.02.2013 11:15:31 Contents Introduction Inhalt Einführung I. 1787: The work Its background, genesis, significance and impact . . . . 7 I. 1787: Das Werk II.The Autograph Its clear, its twisted paths . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9 Sein Umfeld, seine Entstehung, Bedeutung und Wirkung 15 II.Das Autograph Seine eindeutigen, seine verschlungenen Pfade . . . . . . 17 Notes and References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Anmerkungen . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21 Watermark No. 55 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 Wasserzeichen Nr. 55 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22 Facsimile of the autograph fragment KV 525 a . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Faksimile des autographen Fragments KV 525 a . . . . . . . . . . . . . 24 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 5 27.02.2013 11:15:31 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 6 27.02.2013 11:15:31 Introduction I. 1787: The work. Its background, genesis, significance and impact At the beginning of the year 1787, Mozart and his wife travelled to Prague for the first time, at the invitation of “a circle of great connoisseurs and lovers of music” in the town. On 15th January, Mozart sent news to his friend Gottfried von Jacquin in Vienna: “As soon as we arrived, we had our hands full with things to do.” In the evening they also attended a ball, and the composer was able, with great satisfaction, to assert: “But I watched with great pleasure how all these people, to the music of my Figaro transformed entirely into contredances and German dances, were leaping around in such heartfelt merriment; – […] and endless Figaro; certainly a great honour for me.” Two days later, Mozart attended a performance of Figaro, premièred in Vienna on 1st May 1786 and incorporated into the Prague repertoire at the end of 1786 by the Bondinische Gesellschaft der Opernvirtuosen [Bondini’s Association of Opera Virtuosi], the first opera on a libretto by Lorenzo Da Ponte. At least one performance, that on 22nd January, was then directed by Mozart himself. After the great success of Figaro in the Bohemian capital, the composer received from the impresario Pasquale Bondini a commission for a new opera: with the première of Don Giovanni KV 527 in the Ständetheater [Es- tates Theatre], Prague, on 29th October 1787, Mozart experienced an instant and resounding success on stage. The Mozarts had for this reason set off anew for Prague at the beginning of October (their second journey to that destination inspired Eduard Mörike to his novella, published in 1856, Mozart auf der Reise nach Prag, surely the most moving example of literary empathy with Mozart). From the end of March, therefore, to the end of September in what was without doubt the “great” year of 17871, Don Giovanni, the “opera of all operas” (E. T. A. Hoffmann) was the focus of Mozart’s creative work in Vienna. He furthermore composed a considerable number of other important works, including some of his most beautiful songs, two bass arias, the string quintets KV 515 and KV 516, the keyboard sonata for four hands KV 521, the keyboard / violin sonata KV 526 and the supposedly twinned works in the genre of ensemble music for social occasions, namely Ein musikalischer Spaß for strings and two horns KV 522 and Eine kleine Nachtmusik KV 525 for “2 vio­lini, Viola e Bassi”2, meaning performance either by a chamber orchestra with several instruments per part or by solo instruments with violoncello and double bass. Almost completely ignored during the 19th century, the “Night Music” has however mutated since the beginning of the last century into an “evergreen”, so that today’s concert programmes, or even the everyday activities of the public media, are unthinkable without it. In the cosmos of so-called “seri- 7 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 7 27.02.2013 11:15:31 ous” music, it has acquired a compositionally exemplary character in terms of form, sonority and structure. At the same time, the general public will hardly be aware that this “little” work has not been transmitted in its entirety: the first Menuett und trio3, referred to by Mozart in his handwritten work catalogue, has long been missing. Two further particularities of the “great” year 1787 should also be mentioned. One striking point is that in his catalogue, the Verzeich­ nüß aller meiner Werke, kept since 1784, Mozart lists no more concertos for keyboard and orchestra. The time of the famous Vienna keyboard concertos had closed with the concerto KV 503, with its large forces and sweeping dimensions, on 4th December 1786; his so-called “academies”, for which he had written the concertos (“for my own use”), were unresponsive to efforts to impart new life. In this area, his star was already setting – only two “latecomers” would be added: KV 537 (1788) and KV 595, dated to the beginning of the year of his death. The other point is that the successes in Prague with Le nozze di Figaro and Don Giovanni were noted attentively at the Imperial Court in Vienna. Mozart was named “Imperial-Royal Chamber Composer” on 7th December 1787, which meant increased income and a gain in prestige for the composer. He thus found himself at an important point in his career. “Now I am standing at the gateway to my happiness”, to apply Mozart’s phrasing from a later letter to Michael Puchberg, his fellow Masonic brother.4 Finally, one should mention the death of his father, Leopold, once the strict teacher, the dominant “father figure”, to whom the son wrote, in a last and comforting letter of 4th April 1787 to the sick man, those famous and variously interpretable lines about death. Leopold Mozart died on 28th May 1787, alone in the large residence occupied by the Mozarts since 1773, the Salzburg Tanzmeisterhaus [“Dancing Master’s House”] on the former Hannibal Square, today Makart Square. How did Mozart receive the news from Salzburg, what effect, of whatever kind, did it have on him? – Like so much in Mozart’s private life, this can hardly be established, but the dissolution of the estate and the dividing of the inheritance certainly accompanied and burdened him until at least the end of September 1787, that is, more or less for the duration of the composing of Don Giovanni. * * * Now, whether this piece for strings from the year of Don Giovanni should be termed “Serenade” (incorrect according to its genre), as in the first (parts) edition of 1825 by J. André, Offenbach am Main (there Sérénade), in the so-called Alte Mozart-Ausgabe [Old Mozart Edition] (1883) or in the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe [New Mozart Edition] (NMA, 1964), but also in all editions of the Köchel-Verzeichnis, or whether the rubric “Divertimento” should be applied, or if indeed – perhaps most accurately – one should only speak of D i e [ T h e ] kleine Nachtmusik as a singularity must be left undecided here. – The genesis of the work is obscure, no compositional commission is documented, but recently Wolf-Dieter Seiffert has attempted to identify a possible occasion for the work amongst Mozart’s circle of the Vienna decade (but also in Salzburg before that). He points to the particular importance attached to name-days in southern Germany and Austria and thus, of course, in Mozart’s earlier centre, Salzburg. If one accepts Seiffert’s promising approach, the most likely relevant member of the Vienna circle is Baron Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin, then the 60-year-old father of Mozart’s friend Gottfried von Jacquin 8 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 8 27.02.2013 11:15:31 Einführung I. 1787: Das Werk. Sein Umfeld, seine Entstehung, Bedeutung und Wirkung Zu Beginn des Jahres 1787 reiste das Ehepaar Mozart auf Einladung einer dortigen »Gesellschaft grosser kenner und Liebhaber« erstmals nach Prag. Am 15. Januar berichtete Mozart seinem Freund Gottfried von Jacquin in Wien: »Gleich bey unserer Ankunft hatten wir über hals und kopf zu thun«. Am Abend noch wurde ein Ball besucht, und der Komponist konnte mit großer Genugtuung feststellen: »ich sah aber mit ganzem Vergnügen zu, wie alle diese leute auf die Musick meines figaro, in lauter Contretänze und teutsche verwandelt, so innig vergnügt herumsprangen; – […] und Ewig figaro; gewis grosse Ehre für mich«. Zwei Tage später besuchte Mozart eine Aufführung des am 1. Mai 1786 in Wien uraufgeführten, Ende 1786 durch die Bondinische Gesellschaft der Opernvirtuosen in das Prager Repertoire aufgenommenen Figaro, der ersten Oper auf ein Libretto von Lorenzo Da Ponte. Wenigstens eine weitere Aufführung, jene am 22. Januar, leitete Mozart dann selbst. Nach dem großen Erfolg des Figaro in der böhmischen Hauptstadt erhielt der Komponist durch den Impresario Pasquale Bondini einen neuen Opernauftrag: Mit der Uraufführung des Don Giovanni KV 527 am 29. Oktober 1787 im Ständetheater Prag erlebte Mozart auf Anhieb einen durchschlagenden Bühnenerfolg. Die Mozarts waren deshalb Anfang Oktober erneut nach Prag aufgebrochen (ihre zweite Reise dorthin inspirierte Eduard Mörike zu seiner 1856 publizierten Novelle Mozart auf der Reise nach Prag, der sicherlich bewegendsten literarischen Mozart-Annäherung). Im zweifellos »großen« Jahr 17871 stand also von Ende März bis Ende September 1787 der Don Giovanni, die »Oper aller Opern« (E. T. A. Hoffmann) im Zentrum von Mozarts Schaffen in Wien. Darüber hinaus hat er noch eine beträchtliche Reihe anderer wichtiger Werke komponiert, so einige seiner schönsten Lieder, zwei BassArien, die Streichquintette KV 515 und KV 516, die Sonate für Klavier zu vier Händen KV 521, die Klavier-Violinsonate KV 526 und das vermeintliche Zwillingspaar im Genre der gesellschaftsgebundenen Ensemblemusik, nämlich Ein musikalischer Spaß für Streicher und zwei Hörner KV 522 und Eine kleine Nachtmusik KV 525 für »2 violini, Viola e Bassi«2, das heißt entweder chorisch für Kammerorchester oder solistisch mit Violoncello und Kontrabass zu besetzen. Im 19. Jahrhundert kaum zur Kenntnis genommen, ist die »Nachtmusik« jedoch seit Beginn des vorigen Jahrhunderts zum »Evergreen« mutiert, ist aus dem heutigen Konzertleben, aber auch aus dem Alltag der öffentlichen Medien nicht mehr wegzudenken. Im Kosmos der sogenannten E-Musik kommt ihr ein in Form, Klang und Struktur kompositorischer Vorbildcharakter zu. Dabei wird dem breiten Publikum kaum bewusst sein, dass das »kleine« Werk nicht vollständig 15 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 15 27.02.2013 11:15:32 überliefert ist: Es fehlt seit Langem das von Mozart in seinem eigenhändigen Werkverzeichnis erwähnte erste Menuett und trio.3 Zwei Besonderheiten des »großen« Jahres 1787 verdienen noch erwähnt zu werden. Zum einen fällt auf, dass Mozart in das Verzeich­ nüß aller meiner Werke, das er mit Februar 1784 begonnen hatte, für 1787 kein Konzert für Klavier und Orchester mehr eingetragen hat. Die Zeit der berühmten Wiener Klavierkonzerte war mit dem groß besetzten und weit dimensionierten Konzert KV 503 am 4. Dezember 1786 zu Ende gegangen; seine sogenannten Akademien, für die er seine Konzerte (»zum eigenen Gebrauch«) geschrieben hatte, wollten nicht neu aufleben. Auf diesem Feld war sein Stern im Sinken – es folgten nur noch zwei »Nachzügler«: KV 537 (1788) und KV 595, zu Beginn des Todesjahrs datiert. Zum andern sind die Prager Erfolge von Le nozze di Figaro und Don Giovanni am kaiserlichen Hof in Wien aufmerksam wahrgenommen worden. Mozart wurde am 7. Dezember 1787 zum »k. k. Kammer-Kompositeur« ernannt, was für den Komponisten vermehrte Einkünfte und gesteigertes Prestige bedeutete. Er befand sich also an einem wichtigen Punkt seiner Laufbahn: »Nun stehe ich vor der Pforte meines Glückes«, um eine Formulierung Mozarts aus einem späteren Brief an seinen freimaurerischen Logenbruder Michael Puch­ berg aufzunehmen.4 Schließlich ist auch der Tod von Vater Leopold, des einstigen strengen Lehrers, des »Übervaters«, zu erwähnen, an den der Sohn in einem letzten, einem Trostbrief für den kranken Mann vom 4. April 1787 berühmte und in durchaus verschiedener Weise zu interpretierende Sätze über den Tod geschrieben hatte. Leopold Mozart starb am 28. Mai 1787 vereinsamt in dem 1773 bezogenen großen Wohn- haus der Mozarts, dem Salzburger »Tanzmeisterhaus« am damaligen Hannibal- (heute Makart-) Platz. Wie Mozart die Nachricht aus Salzburg aufgenommen hat, ob er von ihr, in welcher Weise auch immer, betroffen war, ist, wie so vieles in Mozarts privatem Leben, kaum nachzuvollziehen, doch haben ihn zumindest Nachlass-Auflösung und Erbteilung bis Ende September 1787, also mehr oder weniger die Zeit der Don Giovanni-Komposition hindurch, begleitet und belastet. * * * Ob nun das Streicherstück aus dem Don Giovanni-Jahr (der Gattung nach nicht korrekt) als »Serenade« zu bezeichnen ist, wie 1825 im (Stimmen-)Erstdruck bei J. André, Offenbach am Main (dort Séré­ nade), in der sogenannten Alten Mozart-Ausgabe (1883) oder in der Neuen Mozart-Ausgabe (NMA,1964), aber auch in allen Auflagen des Köchel-Verzeichnisses, oder ob es als »Divertimento« rubriziert werden sollte oder ob gar – vielleicht am zutreffendsten – nur von D e r kleinen Nachtmusik als Solitär zu reden wäre, mag hier unentschieden bleiben. – Die Entstehungsgeschichte des Werks liegt im Dunkeln, ein Kompositionsauftrag ist nicht dokumentiert, doch hat nun jüngst Wolf-Dieter Seiffert versucht, in Mozarts Umkreis des Wiener Jahrzehnts (aber auch zuvor in Salzburg) einen Anlass zu bestimmen. Er weist auf die besondere Bedeutung hin, die die Feier des Namenstags im süddeutsch-österreichischen Raum und eben auch in Mozarts früher, der Salzburger Lebenswelt hatte. Zieht man Seifferts erfolgversprechenden Ansatz in Betracht, dann kommt aus dem Wiener Kreis vor allem Freiherr Nikolaus Joseph von Jacquin, der damals 60-jährige Vater des Mozart-Freundes Gottfried von Jacquin (1767–1792), in Frage: Gottfried könnte bei Mozart für den 16 Nachtmusik-Einleitung_BVK-2282_4korr.indd 16 27.02.2013 11:15:32