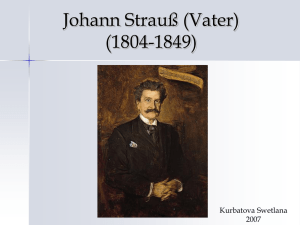

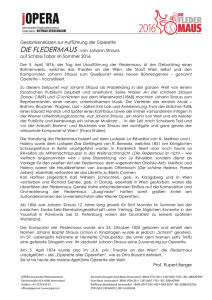

Strauss I

Werbung