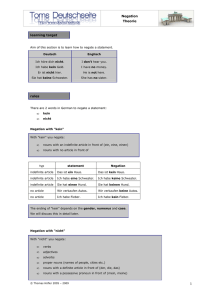

A Comparative Analysis of the Correct Usage of "nicht" and "kein" in

Werbung