Meine Analysis III Zusammenfassung ()

Werbung

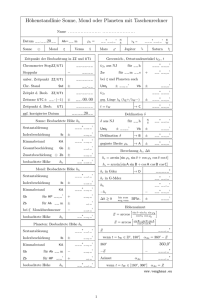

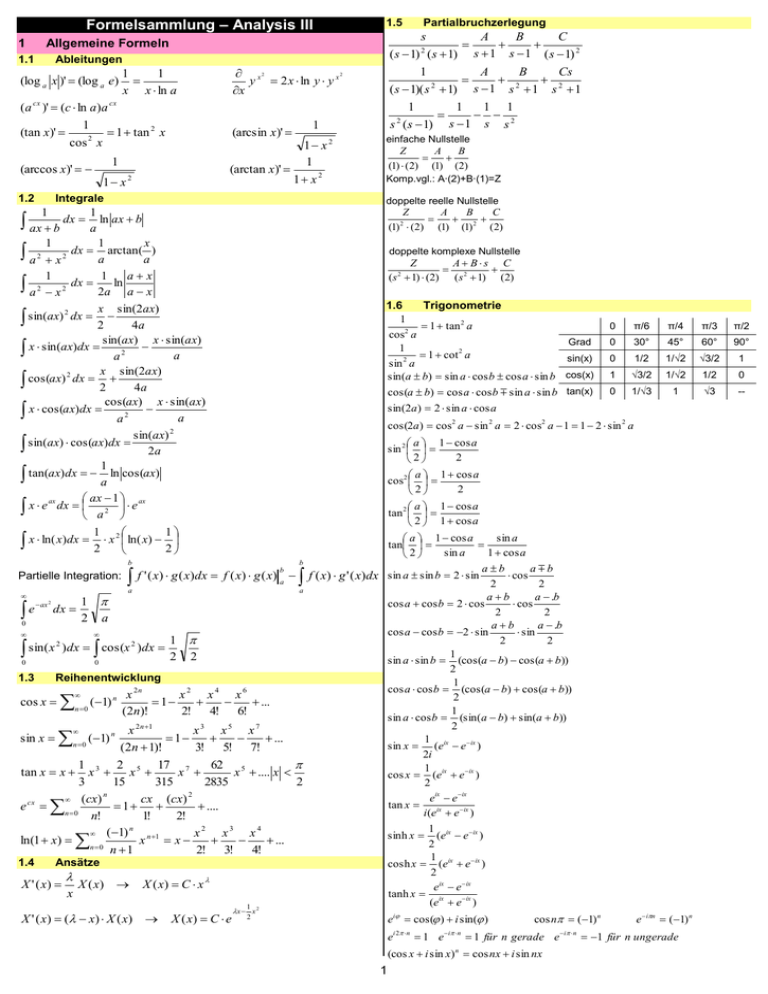

Formelsammlung – Analysis III

1

1.2

2

1 x 2

1

(arctan x)'

1 x 2

1 x 2

2

1

(arcsin x)'

1

(arccos x)'

x

y 2 x ln y y x

x

1

1

x x ln a

(a cx )' (c ln a)a cx

1

(tan x)'

1 tan 2 x

cos 2 x

A

B

C

( s 1) ( s 1) s 1 s 1 ( s 1) 2

1

A

B

Cs

( s 1)( s 2 1) s 1 s 2 1 s 2 1

1

1

1 1

2

2

s ( s 1) s 1 s s

2

Ableitungen

(log a x )' (log a e)

Partialbruchzerlegung

s

Allgemeine Formeln

1.1

1.5

Integrale

einfache Nullstelle

Z

A

B

(1) (2) (1) (2)

Komp.vgl.: A∙(2)+B∙(1)=Z

doppelte reelle Nullstelle

1

1

dx ln ax b

ax b

a

1

1

x

dx arctan( )

a

a

a2 x2

1

1

ax

dx

ln

2a a x

a2 x2

x sin(2ax)

sin(ax) 2 dx

2

4a

sin(ax) x sin(ax)

x sin(ax)dx

a

a2

x sin(2ax)

2

cos(ax) dx

2

4a

cos(ax) x sin(ax)

x cos(ax)dx

a

a2

sin(ax) 2

sin(ax) cos(ax)dx

2a

1

tan(ax)dx ln cos(ax)

a

ax 1

x e ax dx 2 e ax

a

1

1

x ln( x)dx x 2 ln( x)

2

2

Z

A

B

C

(1) 2 (2) (1) (1) 2 (2)

doppelte komplexe Nullstelle

Z

A Bs C

( s 2 1) (2) ( s 2 1) (2)

1.6

Trigonometrie

1

1 tan 2 a

cos2 a

1

1 cot 2 a

sin 2 a

sin(a b) sin a cos b cos a sin b

cos(a b) cos a cos b sin a sin b

sin(2a ) 2 sin a cos a

π/6

π/4

0

30°

45°

60°

90°

0

1/2

1/√2

√3/2

1

cos(x)

1

√3/2

1/√2

1/2

0

tan(x)

0

1/√3

1

√3

--

a 1 cos a

sin 2

2

2

a 1 cos a

cos2

2

2

X ' ( x ) ( x ) X ( x )

X ( x) C e

x x

ei cos( ) i sin( )

2

cos n (1) n

e in (1) n

ei 2 n 1 e i n 1 für n gerade e i n 1 für n ungerade

(cos x i sin x) n cos nx i sin nx

1

π/2

Grad

cos(2a ) cos2 a sin 2 a 2 cos2 a 1 1 2 sin 2 a

π/3

sin(x)

a 1 cos a

tan 2

2 1 cos a

sin a

a 1 cos a

tan

2

sin

a

1

cos a

b

b

ab

ab

b

cos

Partielle Integration: f ' ( x) g ( x)dx f ( x) g ( x) a f ( x) g ' ( x)dx sin a sin b 2 sin

2

2

a

a

a

b

a

.b

2

1

cos a cos b 2 cos

cos

e ax dx

2

2

2 a

0

ab

a .b

cos a cos b 2 sin

sin

2

2

1

sin( x 2 )dx cos(x 2 )dx

1

2

2

sin a sin b (cos(a b) cos(a b))

0

0

2

1.3

Reihenentwicklung

1

cos a cos b (cos(a b) cos(a b))

2n

x2 x4 x6

n x

2

cos x n 0 (1)

1

...

1

(2n)!

2! 4! 6!

sin a cos b (sin( a b) sin(a b))

2

x 2 n 1

x3 x5 x7

n

sin x n 0 (1)

1

...

1 ix

sin x (e e ix )

(2n 1)!

3! 5! 7!

2i

1 3 2 5 17 7

62 5

1

tan x x x x

x

x .... x

cos x (eix e ix )

3

15

315

2835

2

2

n

2

eix e ix

(

cx

)

(

cx

)

cx

tan x ix

e cx n 0

1

....

i (e e ix )

n!

1!

2!

n

1

( 1)

x2 x3 x4

sinh x (eix e ix )

ln(1 x) n 0

x n 1 x

...

2

n 1

2! 3! 4!

1

1.4

Ansätze

cosh x (eix e ix )

2

X ' ( x) X ( x) X ( x) C x

eix e ix

tanh x ix

x

(e e ix )

1 2

0

2

2.1

PDGen

5

Seperation der Variablen

Ansatz: u( x, t ) X ( x) T (t )

Die Wellengleichung

1

Problem:

utt u xx 0

c2

Allg. Lösung: u ( x, t ) F ( x ct ) G ( x ct )

Beispiel:

Allg. Lösung des Anfangswertproblems:

1

c 2 u tt ( x, t ) u ( x, t ) 0

u ( x,0) f ( x)

1

1

u ( x,0) g ( x) u ( x, t ) f ( x ct ) f ( x ct )

t

2

2c

Gesucht: Lösungen der Form: u( x, y) f ( x) g ( y)

1. f ' ' ( x)

g ' ' ( y)

C

f ( x)

g ( y)

2.1.1

x ct

x ct

g ( y ) dy

2.

Beispiel Wellengleichung Prüfung F05

4u tt u xx e t

u ( x,0) 0

u ( x,0) 0

t

3. aus (*) folgt, daß f (0) f ( L) 0 gilt. Nur die Lösung für C<0

macht Sinn für diese Forderung.

4. Es folgt A = 0 und aus B sin( C L) 0 , daß

k x

f ( x) B sin(

)

L

5. da C< 0 ist g ( y) D e k y L E e k y L

6. aus u ( x,0) 0 folgt daß g (0) 0 also D E

k y

k x

) sinh(

)

3

L

L

K

sinh(4 )

8. aus einsetzen folgt noch daß k 4 und

3

4 x

4 y

9. Die Lösung ist also

u ( x, y)

sin(

) sinh(

)

sinh(4 )

L

L

6

Inhomogene PDGlen

2.2

Wärmeleitungsgleichung

Problem: u u 0

xx

u ( x,0) f ( x)

1. Fouriertransformierte:

1

uˆ (k , t )

u( x, t ) e ikx dx

u ( x, t )

uˆ ( x, t ) e ikx dk

2

1

2. Ableiten: u t ( x, t )

uˆ t ( x, t ) e ikx dk

2

1

u xx ( x, t )

uˆ ( x, t ) k 2 e ikx dk

22

k

3. Einsetzen: uˆ (k , t ) k uˆ(k , t ) 0 uˆ(k ,0) fˆ (k ) uˆ(k , t ) fˆ (k )e

4. Rücktrafo: u ( x, t )

1

4 t

u t au xx sin x t 0, x R

u ( x,0) 0 x R

f ( x' ) e

Wärmeleitungskern Kt: K ( x x' )

t

Lösung: u( x, t )

Die allg. Lösung eines inhomogenen Randwertproblems ist die allg.

Lösung des zugehörigen homogenen Problems plus eine partikuläre

Lösung des inhomogenen Problems.

Beispiel:

( x x ') 2

4t

1

4 t

e

2

t

Vorgehen:

1. u ( x, t ) u H ( x, t ) u P ( x, t )

2. Finde partikuläre Lösung

3. Setze diese in AB ein

4. Löse das homogene Problem

5. Zusammensetzen

dx'

( x x ') 2

4t

K t ( x x' ) f ( x' )dx'

Lösungsweg:

1.

sin x

a

f f g f h

Kettenregel: f ( g ( x), h( x))

1

0

2. t 0 u ( x,0) u H ( x,0)

x g x h x

a sin x

x

r

cos

y

r

sin

f ( x, t ) f (r ( x, y), ( x, t )) Polarkoordinaten

1

u H ( x,0)

( f ( x))

f ( x, y)

a sin x

Was ist

in Polarkoordinaten?

x

(u H ) t a (u H ) xx 0

r r

x y

sin

cos

sin Inverse x y cos

r 4. u H ( x, t ) K t ( x x' ) f ( x)dx'

r r

R

cos

x y r sin r cos

x y sin

r

1

sin x

K t ( x x' ) f ( x)dx'

5. u ( x, t )

a R

a

4

Superposition

3

C L k , also

7. u ( x, y) K sin(

1

t 1

t 1 et 1 t

u ( x, t ) x x

e t 1

4

2 4

2 4 4 4

t

A e C x B e C x (C 0)

f ( x) A cos( C x) B sin( C x) (C 0)

A x B (C 0)

D e C y E e C x (C 0)

g ( y ) D cos( C y ) E sin( C y ) (C 0)

D y E (C 0)

t

t et

u ( x, t ) u h ( x , t ) u p ( x , t ) F x G x

2

2 4

1

ableiten

u ( x,0) F ( x) G ( x) 0

u ' ( x,0) F ' ( x) G ' ( x) 0

4

1

1

1

u t ( x,0) F ' ( x) G ' ( x) 0

2

2

4

x

F ( x) 4 C

1

F ' ( x)

x 1

4

G ( x) C

4 4

u xx u yy 0

u (0, y ) u ( L, y ) 0 (*)

u ( x,0) 0 L 0

u ( x, L) 3 sin 4 x

L

Koordinatentransformation

0 a u p ' ' sin x u p

Lineare PDG hat die Form Lu=b, wobei L Diffentialoperator und b eine

gegebene Fkt der unabh. Variablen ist. Homogen, wenn b=0.

Sind u1,…,un Lösungen der linearen PDG Lu=0, so ist auch jede

Linearkombination u=c1u1+…..+cnun eine Lösung.

2

7

Fourier-Reihen

7.1

8

f ( x)

n

2in

x

L

cn e

1

cn

L

mit

L

0

e

2in

x

L

f ( x)dx

f(x) sei eine zweimal stetig differenzierbare L-periodische Funktion

Beispiel von periodischen Fkten:

2π-periodische Fkten: cos(x), sin(x), eix

L-periodische Fkten:cos(2πx/L), sin(2πx/L), ei 2πx/L

L, L/n periodische Fkten: (2πnx/L), sin(2πnx/L), ei 2πnx/L

Integrationsintervall

Man kann auf beliebigem Intervall der Periodenlänge integrieren:

L

La

a

L

... ... ... ...

0

a

0

2

fˆ (k ) f ( x) e ikx dx

f ( x) e ax

fˆ ( x)

k2

0

x

cn

1

2

1

2

1

2

L

f ( x) e

dx

1

2

1

e

0

0

1 1 inx

e inx dx

e

2 2 ni in

1

e in e in e 0

für n ungerade : e in 1 c n

0

1 inx

e

in

0

2

2n2

L/2

L / 2

L/2

L / 2

f ( x) 0

L/2

f ( x) 2 f ( x)

0

2 L2

2n

f ( x) sin

x dx

l

2

L

L

2n

b sin

x

n 1 n

L

4 L2

2n

bn

f ( x) sin

x dx n 1

L 0

L

a

2n

x

Gerade Funktion: f ( x ) 0 n 1 a n cos

2

L

a

Ungerade Funktion: f ( x) 0

2

4

an

L

L 2

0

e

e

ik

a x

2a

2n

f ( x) cos

x dx n 0

L

ikx

dx

2

k2

dx e 4 a

e

2

ik

k2

a x

2a 4a2

dx

k2

e ay dy e 4 a

2

f ( x ) e ikx dx1 ...dxn

en ax e ikx dx

2

e

( ak 2 bk c )

e

x2

1

dk

1 k 2

n

2 2e

a

2n

2n

f ( x) 0 n 1 a n cos

x bn sin

x

2

L

L

2 L2

2n

a n f ( x) cos

x dx

L l 2

L

bn

n

7.2

Reelle Darstellung

reellwerte Lösungen sind Spezialfälle von komplexen Lösungen

Ein Fkt auf R ist: gerade falls f(-x)=f(x) und ungerade falls f(-x)=-f(x)

Produkt:

gerade mal gerade = gerade

ungerade mal ungerade = gerade

ungerade mal gerade = ungerade

Falls f(x) gerade ist, dann

e

ax 2

in

2 2 n 2

2 2 n 2

in

für n gerade : e

1 cn 0

Falls f(x) ungerade ist, dann

2

a

f ( x)

1

2

n

fˆ (k ) e ikx dk1 ...dk n

Nützliche Rechnungen:

e inx dx

fˆ ( x) e ikx dk

Eine Fkt f: R in C nimmt genau dann ihre Werte in R an, wenn

Fouriertransformierte folgende Relation erfüllt: fˆ (k ) fˆ (k )

0

fˆ (k )

2

1 1

2 ni

In n-dimensionalen Räumen:

x

1 e inx dx

0

0

0

x inx

x

1 e dx 1

1 e inx dx partielle Integr :

2 0

0

0

x

1 inx

1 1 e inx dx

e

1

in

in

0

0

x

1 1

1 inx

inx

in e 1 in e dx

1

L

2in

x

L

e 4a

2 periodisch

Beispiel:

nützlich : ... ...

a

1

2

f ( x)

Beispiel

f ( x) 1

Fouriertransformation

PDG auf endlichem Intervall → Fourierreihen

Lin. PDG auf unendlichem Intervall → Fouriertransformation

L unendl. groß, L → ∞, Δk=2π/L → 0, Summe → Integral

Komplexe Darstellung

n

a

dk

e

a

k2

4a

e

ˆ

fˆ ( x) 2 fˆ ( x)

b2

c

4a

dx

Anleitung: (für inhom. DGl. mit AB)

i) Fourriertrafo der DG mit fn=(ik)nf^

ii) Lösen der DG

iii) Fourriertrafo der AB

iv) AB in DG einsetzen

v) Rücktrafo

8.1

Wärmeleitungsgleichung

AWP: u t ( x, t ) u xx ( x, t ) 0

u ( x,0) f ( x)

i) Fourriertrafo der DG: uˆt (k , t ) (ik ) u(k , t ) 0

2

ii) Lösen der DG: uˆ (k , t ) C e k

iii) Fourriertrafo der AB: fˆ (k )

t

2

f ( x) e ikx dx

iv) AB in DG einsetzen: uˆ (k , t ) fˆ ( x) e

v) Rücktrafo: u ( x, t )

1

2

k 2 t

2

fˆ ( x) e k t ixk dk

u( x, t ) Kt ( x x' ) f ( x' )dx'

Lösung:

Mit Wärmeleitungskern: K t ( x x' )

Mit:

K ( x x' )dx 1

t

K t ( x x' ) 0

Inhomogen:

part. Lösung mit rechter Seite

u(x,0)=part.+gegeb. Lösung

in AWP dafür homogen (=0)

neues f(x)

Lösen wie oben

3

1

e

4t

( x x ') 2

4t

9.1

Beispiele

Beispiel A

Laplacetransformation

9

F ( s)

f (t )e

st

dt

AWP:

0

xt (t ) 2 x(t ) t

x ( 0) a

Linearität

i) Laplacetransformierte von DGl: sX ( s ) x(0) 2 X ( s )

1. Ableitungsregel

ii) AB einsetzen:

L f g L f Lg

L f n (t ) s n F (s) s n1 f (0) s n2 f ' (0).... f ( n) (0)

2. Ableitungsregel:

f (t ) t k g (t ) F ( s) (1) k

1

1

(a 2 )

s2

s

iv) Partialbruchzerlegung: X ( s)

f (t ) e

dk

G( s)

ds k

g (t ) F (s) G(s a)

f (t a), t a

L1 e as F ( s ) H (t a) f (t a )

0, t a

Faltungssatz:

AWP:

f(t)

F(s)

δ(t): Deltafkt.

1

H(t): Heavyside

1

s

e at

k!

s k 1

1

sa

1 e at

a

s( s a)

cos(at)

sinh(at)

cosh(at)

1 as

e

s

ρ(t-a) (a>0)

e as

f’(t)

sF(s)-f(0)

f’’(t)

s2F(s)-sf(0)-f’(0)

f ( )d

1

F ( s)

s

f(t-a)

e as F (s)

f(at)

1

s

F( )

a

a

0

e at f (t )

1

f (t )

t

1

s 1

X ( s)

v) Inverse Laplacetransformierte:

3

1

1

4s 1 4s 1 2s 12

1

3 t

x(t ) e t e t

4

4 2

F(s-a)

F (s)ds

s

Vorgehen:

i) Laplacetransformierte von DGl

ii) AB einsetzen

iii) X(s)=…

iv) Partialbruchzerlegung

v) Inverse Laplacetransformierte

4

1

s 1

1 1

1

1

s 1 2

s 1 s 1

s 1 s 1 s 1

2

iv) Partialbruchzerlegung:

a

s2 a2

s

s2 a2

a

s2 a2

s

s2 a2

H(t-a) (a>0)

t

x t (0) x(0) 1

iii) X(s)=… X ( s )

1, t a

H (t a )

0. t a

Wichtige Laplacetransformationen:

sin(at)

x tt (t ) x(t ) e t

ii) AB einsetzen: s 2 X ( s ) s 1 X ( s )

Heaviside-Funktion:

tk

1

t 1

x(t ) a e 2t

4

2 4

2

i) Laplacetrafo von DGl: s X ( s ) s x' (0) x(0) X ( s )

t

L f (t t ' ) g (t ' )dt ' F ( s) G( s)

0

1, t 0

H (t )

0. t 0

a

1

1

1

2

s a 2s

4s 4( s 2)

v) Inverse Laplacetransformierte:

Beispiel B

2. Verschiebungssatz:

1

s2

iii) X(s)=… X ( s )

1. Verschiebungssatz:

at

sX ( s ) a 2 X ( s )

1

s2

10

a( x, t , u )ut c( x, t , u ) u x d ( x, t , u )

Laplacegleichung

u 0

10.1

u ( x,0) f ( x)

Radiales Dirichlet-Problem in der Ebene

u u rr

1

1

u r 2 u 0

r

r

Allgemeine Lösung:

u (r , ) n , n 0 ( An r B n r

n

n

)e

in

C 0 D0 log r

Sei a(x,t,u) ≠ 0. Das AWPhat für jede gegebene (diff.bare) Funktion f

eine eindeutige Lösung u(x,t), die im Bereich {(x,t), t < T0(x)} für eine

gewisse Funktion T0(x) definiert ist.

1. Annahmen:

x x(t )

z (t ) u ( x(t ), t )

2. Zu erfüllen:

z d ( x, t , z )

z, x auflösen

x c( x, t , z )

An, Bn, C0, D0 ergeben sich eindeutig aus den Randbedingungen

10.1.1 Typ I: Kreisscheibe

u ( r , ) 0

u (a, ) f ( )

(*)

Aus Stetigkeit für r=0 schliest man, daß keine negativen Potenzen und 3. x(0)=x0 und z(0)=f(x0)

log(r) nicht auftauchen. Bn=0 und D0=0

Lösung:

4. x(t) = … und z(t) = …

u (r , ) n , n 0 An r e in

n

n

n , n 0

An a e

in

5. Lösung: u ( x, t ) z (t ) .....

11.1 Allgemeine quasilineare PDG mit zwei unabh. Variablen

f ( )

ut u x 0 t 0

10.1.2 Typ II: Komplement aus Kreisscheibe

u ( x,0) f ( x)

u (r , ) 0 r a

u (a, ) f ( )

u (r , ) ist beschränkt für r

1. Annahmen x x(t )

z (t ) u ( x(t ), t )

Lösung:

Kettenregel:

u (r , ) n , n 0 An r

n , n 0

An a

n

n

dz(t )

dx(t )

ut ( x(t ), t ) u x ( x(t ), t )

dt

dt

dx(t )

c( x(t ), t ) 1

dt

2. Zu erfüllen:

dz(t )

d ( x(t ), t ) 0

dt

e in

e in f ( )

10.1.3 Typ III: Kreisring (Annulus)

u (r , ) 0 R1 r R2

u ( R1 , ) f 1 ( )

u ( R2 , ) f 2 ( )

3. x(0) = x0 und z(0) = f(x0) = u(x(0),0)

f 1 ( ) n , n 0 ( An R1 B n R1 )e in C 0 D0 log R1

n

n

f 2 ( ) n , n 0 ( An R 2 B n R 2 )e in C 0 D0 log R 2

n

n

10.2 Poisson-Formel

Die Lösung des Dirichlet-Problems auf der Kreisscheibe mit Radius a

ist gegeben durch die Poisson-Formel:

2

u (r , ) K (r , , ' ) f ( ' )d '

0

K (r , , ' )

10.3

1

a2 r2

2 a 2 2ra cos( ' ) r 2

Mittelwertprinzip

Ist Δu=0 auf einem Gebiet D, so ist der Wert von u an der

Stelle x D gleich dem Mittelwert von u auf der Oberfläche

jeder Kugel in D mit Mittelpunkt x.

1 2

u (0,0)

f ( )d

f ( ) ist die Fkt auf dem Rand

2 0

10.4 Maximumprinzip

Sei Δu=0 auf einem beschränkten, geschlossenen Gebiet D,

dann wir-d das Maximum von u am Rand angenommen:

max u( x), x D max u( x), x D

Minimumprinzip:

min u( x), x D u( x) max u( x), x D

11 Methode der Charakteristiken

Ein PDG erster Ordnung für u=u(x,t) heißt quasilinear, falls sie die

Form (*) besitzt mit gegebenen Funktionen a, b, c.

Beispiele:

ut + ux = u + 1

linear

xut + sin(t)ux = cos(x+t)

linear

ut + uux = 0

quasilinear

2ut + u2ux + cos(x)cos(u) = 0 quasilinear

ut + ux2 = 0

nicht quasilinear

4. x(t) = t + x0 und z(t) = z(0) = f(x0)

u(t + x0, t) = f(x0) x0 = x – t

5. Lösung: u(x,t) = z(x,t) = f(x0) = f(x-t)

11.2 Beispiele

ut x u x x t 0

u ( x ,0 ) f ( x ) t 0

2. x(t) = c = x und z(t) = d = x

3. x(0) = x0 und z(0) = f(x0)

4. x(t) = Aet mit x(0) = x0 = A wird x(t) = x0et

z(t) = x(t) = x0et + D mit z(0) = f(x0) = x0 + D wird D = f(x0) - x0

z(t) = x0et + f(x0) - x0

5. mit x0 = xe-t und f(x0) = f(xe-t ) wird u(x,t) = z(x,t) = x(1- e-t ) + f(xe-t )

11.3 Beispiel Vorlesung

x u x y u y xyu

u (1, y ) y 2

1 y 2

1. Charakteristiken bestimmen

a( x, y, z ) x

1 (t ) 1 (t )

1 (t ) C1e t

b( x, y, z ) y

2 (t ) 2 (t )

2 (t ) C2 e t

c( x, y, z ) x y z 3 (t ) 1 (t ) 2 (t ) 3 (t ) 3 (t ) C1C2 3 C3e C1C2t

mit 1 (t ) 2 (t ) C1e t C 2 e t C1C 2

2. Nebenbedingungen mit γ schreiben

Aus x = 1→ 1, y = y→ s, z = y2→ s2 wird Γ(s) = (1,s,s2)

3. γs(0) = Γ(s)

C1 1

C1 1

s (0) C 2 s C 2 s

C s2 C s2

3

3

et

4. Parameterdarstellung

t

Fäche I stellt sich dar als s (t ) s e

2 st

5. Beschreibung von I in der Form z=u(x,y)

s e

x = et, y = se-t, z = s2est, xy = et se-t

z(s,t) = s2est → (xy)2exyt = (xy)2(et)xy = (xy)2xxy

u(x,y) = z(x,y) = (xy)2xxy

5

11.4

Beispiel Prüfung F06

u

u x x u y 2 e

u ( x,0) f ( x)

1. Charakteristiken

x 1 y x

e

z

z

z0

z 2 e z

x

xx

dz 2dx e z

0

z

z0

y

1 2

x y0

2

e z e z 0 2 x z ln(e z 0 2 x)

2. Nebenbedingungen

y0 y

1 2

x

2

z 0 f ( y0 )

3. Einsetzen

1

f ( y x2 )

2

u ( x, y ) ln(e

12 Klassifikation

12.1

2 x)

Lineare PDG 2. Ordnung mit zwei unabh. Variablen

A u xx 2 B u x , y C u yy D u x E u y F u G 0

A(x,y),….,G(x,y) sind gegebene Funktionen von zwei Variablen

AC - B2 > 0 elliptisch

AC - B2 = 0 parabolisch

AC - B2 < 0 hyperbolisch

Beispiele:

Wellengleichung c-2uxx – uyy = 0 ist hyperbolisch (A = c-2, B = 0, C = 1).

Wärmeleitungsgleichung ux – uyy = 0 ist parabolisch (A = B = 0, C = 1).

Laplacegleichung uxx + uyy = 0 und allg. Poissonglg sind elliptisch.

Invarianz unter Koordinatentransformationen:

Eine Transformation der unhabhängigen Variablen x, y führt eine PDG

in eine neue PDG über, die dann genau die gleiche Klassifikation hat

wie die ursprüngliche PDG.

Bemerkungen:

1. nur die Terme mit höchster Ableitung zählen (A,B,C)

2.

3.

12.2

13

A B

B C

AC - B2 ist die Determinante der Matrix M M

Sind Koeffizienten A, B, C nicht konstant, sondern

Funktionen, die nicht trivial von x und y abhängen, so können

PDG verschiedene Charakter an versch. Punkten haben.

Charakteristiken

Variablentransformation

Allgemeiner Ansatz:

a b x

wobei det A 0

c d y

6