Übung zu Mikro 2 SoSe 05 Lösungen zu Aufgaben der 3. Übung

Werbung

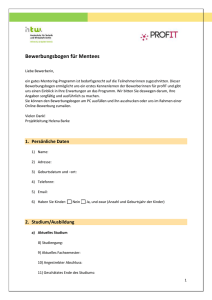

Übung zu Mikro 2 SoSe 05 Lösungen zu Aufgaben der 3. Übung Kapitel 11: Monopolistischer Wettbewerb und Oligopol Aufgabe 5 Monopolistic competition is defined by product differentiation. Each firm earns economic profit by distinguishing its brand from all other brands. This distinction can arise from underlying differences in the product or from differences in advertising. If these competitors merge into a single firm, the resulting monopolist would not produce as many brands, since too much brand competition is internecine (mutually destructive). However, it is unlikely that only one brand would be produced after the merger. Producing several brands with different prices and characteristics is one method of splitting the market into sets of customers with different price elasticities, which may also stimulate overall demand. Aufgabe 9 1. a) Oligopol 1. b) Oligopolmodelle und Vergleich der Ergebnisse: Geteiltes Monopol, Cournot, Bertrand, Stackelberg. 2. Verschiedene Verhaltensannahmen berücksichtigen: Geteiltes Monopol: Gemeinsame Gewinnmaximierung wie ein Monopolist. Cournot: Jedes Unternehmen wählt die gewinnmaximale Menge und nimmt dabei die des anderen als gegeben an. Bertrand: Jedes Unternehmen wählt den gewinnmaximalen Preis und nimmt dabei den des anderen als gegeben an. Stackelberg: Der Stackelberg-Führer bezieht die Reaktion des Folgers (der sich wie ein CournotUnternehmen verhält) in seine Gewinnfunktion ein und wählt so seine gewinnmaximale Menge. 3. Die Gewinnfunktion unter der Berücksichtigung der Annahmen aufstellen und so umformen, daß nur noch eine Variable (meist die Menge des betrachteten Unternehmens) vorhanden ist. Nach dieser Variablen ableiten, Ableitung Null setzen, Gleichung nach der abgeleiteten Variablen auflösen. Bei Cournot muß noch die Reaktionsfunktion von Unternehmen 2 in die von Unternehmen 1 eingesetzt werden. Die anderen Variablen (meist Preis und Gewinn) bestimmen. 6. Tip: Die Grenzerlöskurve bei linearen Nachfragekurven mit P = a – bQ ist immer MR = a - 2bQ. Tip: Grenzerlös und Grenzkosten können getrennt aufgestellt werden, dies erleichtert manchmal die Rechnung. Geteiltes Monopol: MR = 15 - 2Q = MC = 3 2Q = 12, Q = 6, P = 9, Q1 = Q2 = 3 ∏ = 54 - 18 = 36, ∏ 1 = ∏ 2 = 18. Cournot: Die Menge des Unternehmens 2 ist für Unternehmen 1 keine Variable, sondern ein (exogenes) Datum. Sie bleibt deswegen in der Gewinnfunktion. P1 = 15 – Q1 – Q2 = (15 – Q2) – Q1 MR1 = (15 - Q2) - 2Q1 = MC = 3 2Q1 = 12 – Q2 Q1 = 6 - Q2/2 Reaktionsfunktion von 1. Q2 = 6 - Q1/2 Reaktionsfunktion von 2 (die Unternehmen sind identisch, die Reaktionsfunktionen somit symmetrisch). Q1 = Q2 = 4. Q = 8. P = 15 - 8 = 7 TR1 = 7(4) = 28 = TR2 ∏ 1 = 28 - 4(3) = 16 = ∏ 2 ; ∏1 + ∏ 2 = 32. Bertrand: Bei Bertrand braucht keine Gewinnfunktion aufgestellt werden, das Ergebnis kann argumentativ dargelegt werden: Der gewinnmaximale Preis liegt ein bißchen unter dem des Konkurrenten, da die billigere Firma dann sofort die gesamte Nachfrage auf sich zieht. Dies machen beide Firmen so lange, bis sie bei einem Preis gleich den Grenzkosten angekommen sind; weiter senken sie ihre Preise nicht, da sie sonst einen Verlust erwirtschaften würden. Bei einem gleich hohen Preis wird angenommen, daß die Unternehmen jeweils die halbe Nachfrage auf sich ziehen. P = MC = 3 P = 15 - Q Somit ist Q = 12; Q1 = 6 = Q2 TR = 36 TC = 36 ∏ =0 Stackelberg: Der Stackelberg-Führer berücksichtigt die Reaktion des Folgers (der Folger hingegn reagiert nur, und zwar in der gleichen Art wie bei Cournot: die Menge des anderen wird als gegeben angenommen). Dies bedeutet, daß er nicht einfach die Menge Q2 des Folgers in seine eigene Gewinnfunktion (bzw. Erlösfunktion TR1) einsetzt, sondern dessen Reaktionsfunktion. Cournot Reaktionsfunktion der Firma 2: Q2 = 6 - Q1/2 Nachfrage der Firma 1: P = 15 - (6 - Q1/2) - Q1 = 9 - Q1/2. TR1 = PQ1 = (9 - Q1/2)Q1 = 9Q1 – Q1 2 /2 MR1 = 9 - Q1 = MC = 3 => Q1 = 6 Q2 = 6 - Q1/2 = 3 Q=6+3=9 P=6 TR1 = 36 ∏ 1 = 36 - 18 = 18 TR2 = 3(6) = 18 ∏ 2 = 18 - 9 = 9. ∏ 1 + ∏ 2 = 27. |Ableiten nach Q1 . Aufgabe 12 a. If both firms enter the market, and they collude, they will face a marginal revenue curve with twice the slope of the demand curve: MR = 10 - 2Q. Setting marginal revenue equal to marginal cost (the marginal cost of Firm 1, since it is lower than that of Firm 2) to determine the profit-maximizing quantity, Q: 10 - 2Q = 2, or Q = 4. Substituting Q = 4 into the demand function to determine price: P = 10 - 4 = $6. The profit for Firm 1 will be: π1 = (6)(4) - (4 + (2)(4)) = $12. The profit for Firm 2 will be: π2 = (6)(0) - (3 + (3)(0)) = -$3. Total industry profit will be: πT = π1 + π2 = 12 - 3 = $9. If Firm 1 were the only entrant, its profits would be $12 and Firm 2’s would be 0. If Firm 2 were the only entrant, then it would equate marginal revenue with its marginal cost to determine its profit-maximizing quantity: 10 - 2Q2 = 3, or Q2 = 3.5. Substituting Q2 into the demand equation to determine price: P = 10 - 3.5 = $6.5. The profits for Firm 2 will be: π2 = (6.5)(3.5) - (3 + (3)(3.5)) = $9.25 b. In the Cournot model, Firm 1 takes Firm 2’s output as given and maximizes profits. The profit function derived in 2.a becomes π1 = (10 - Q1 - Q2 )Q1 - (4 + 2Q1 ), or π = −4 + 8Q1 − Q12 − Q1Q 2 . Setting the derivative of the profit function with respect to Q1 to zero, we find Firm 1’s reaction function: Q ∂π = 8 − 2 Q1 - Q2 = 0, or Q1 = 4 - 2 . ∂ Q1 2 Similarly, Firm 2’s reaction function is Q Q2 = 3.5 − 1 . 2 To find the Cournot equilibrium, we substitute Firm 2’s reaction function into Firm 1’s reaction function: 1 Q Q1 = 4 − 3.5 − 1 , or Q1 = 3. 2 2 Substituting this value for Q1 into the reaction function for Firm 2, we find Q2 = 2. Substituting the values for Q1 and Q2 into the demand function to determine the equilibrium price: P = 10 - 3 - 2 = $5. The profits for Firms 1 and 2 are equal to π1 = (5)(3) - (4 + (2)(3)) = 5 and π2 = (5)(2) - (3 + (3)(2)) = 1. Rea ct ion F u n ct ion s Q2 10 9 8 7 Q1 = 4 − 6 Q2 2 5 4 3 Q2 = 3.5 − 2 Q1 2 1 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Figure 12.2.b 8 9 10 Q1 c. In order to determine how much Firm 1 will be willing to pay to purchase Firm 2, we must compare Firm 1’s profits in the monopoly situation versus those in an oligopoly. The difference between the two will be what Firm 1 is willing to pay for Firm 2. Substitute the profit-maximizing quantity from part a to determine the price: P = 10 - 4 = $6. The profits for the firm are determined by subtracting total costs from total revenue: π1 = (6)(4) - (4 + (2)(4)), or π1 = $12. We know from part b that the profits for Firm 1 in the oligopoly situation will be $5; therefore, Firm 1 should be willing to pay up to $7, which is the difference between its monopoly profits ($12) and its oligopoly profits ($5). (Note that any other firm would pay only the value of Firm 2’s profit, i.e., $1.) Note, Firm 1 might be able to accomplish its goal of maximizing profit by acting as a Stackelberg leader. If Firm 1 is aware of Firm 2’s reaction function, it can determine its profit-maximizing quantity by substituting for Q2 in its profit function and maximizing with respect to Q1: (in der zweiten Umformung war ein Fehler drin, es fehlt ein Q12, die dritte Umformung war jedoch wieder richtig.) π 1 = −4 + 8Q1 − Q12 − Q1Q 2 , or π = −4 + 8Q − Q 2 − 3.5 − Q1 1 1 1 π = −4 + 4.5Q1 − Q , or 2 1 Q12 . 2 Therefore ∂π = 4 .5 − Q 1 = 0 , or Q 1 = 4 .5. ∂Q1 4.5 Q2 = 3.5 − = 1.25. 2 Substituting Q1 and Q2 into the demand equation to determine the price: P = 10 - 4.5 - 1.25 = $4.25. Profits for Firm 1 are: π1 = (4.25)(4.5) - (4 + (2)(4.5)) = $6.125, and profits for Firm 2 are: π2 = (4.25)(1.25) - (3 + (3)(1.25)) = -$1.4375. Although Firm 2 covers average variable costs in the short run, it will go out of business in the long run. Therefore, Firm 1 should drive Firm 2 out of business instead of buying it. If this is illegal, Firm 1 would have to resort to purchasing Firm 2, as discussed above.

![Aufgabenblatt 9 Aufgabe 1 [Cournot–Gleichgewicht und Kooperation]](http://s1.studylibde.com/store/data/001957943_1-2e6d359103c4b453dc7370242c782f0d-300x300.png)